Beyond ‘Citizens United’: How the Supreme Court Empowered the Very Wealthiest in Elections

Only ten years ago, elections weren’t fueled by secret money, but on the sixth anniversary of Citizens United, the political landscape it helped create has become clear.

Cross-posted on Medium

On the sixth anniversary of Citizens United, the political landscape it helped create has become clear. Million-dollar contributions fund super PACs, individuals can write $5 million checks directly to candidates and their parties, and the odds that an ordinary citizen can successfully run for office have grown longer.

It may seem that the Constitution requires us to endure this dystopian campaign finance regime, but the reality is that it is the handiwork of only five Supreme Court justices — and only in the last decade. There is nothing about today’s money in politics rules that is permanent or inevitable. It’s worth considering how four widely-deplored elements of today’s campaign finance system came about in such a short time.

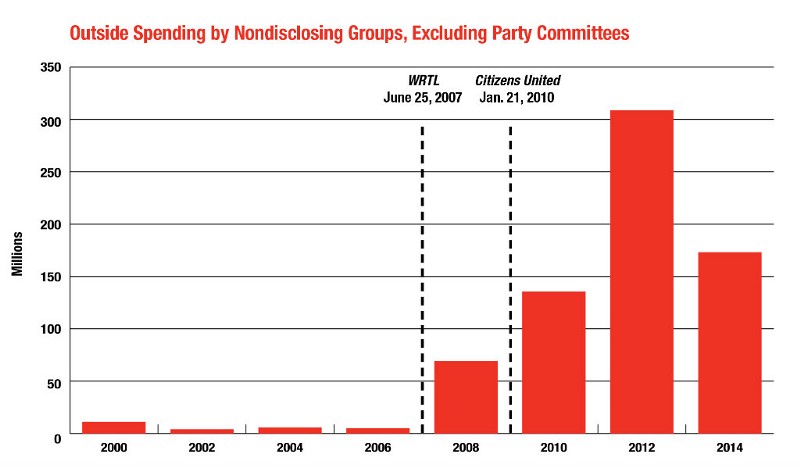

Only ten years ago, elections weren’t fueled by secret money, and outside groups were restricted in their election spending. But when the Court first loosened those restrictions in 2007’s Wisconsin Right to Life, and then eliminated them with Citizens United in 2010, outside spending surged.Making matters worse, the FEC and the IRS are either unable or unwilling to enforce regulations that would require disclosure of donors by certain outside groups. For all intents and purposes, so long as these “social welfare organizations” and trade associations don’t spend too much money on politics, they need not disclose their donors.

For most of the 2000’s, these entities, known as “dark money” groups, spent practically nothing on campaigns. But in the wake of the first Court decision in 2007, organizations that do not disclose their donors spent more than $70 million. In 2012, after Citizens United, they spent more than $300 million.

Already, undisclosed spending in the 2016 cycle is outpacing all prior elections. Though the Court often speaks positively about the importance of disclosure, their decisions allowing for unlimited independent spending laid the groundwork for unlimited secret spending.

Eight years ago, wealthy and well-connected candidates had a harder time drowning out the voice of their opponents. Under federal law at that time, if a wealthy candidate contributed more than $350,000 of their own money to their campaign, contribution limits on her opponent were raised to help make up the difference. And several states had public financing systems with similar provisions to help publicly-financed candidates remain competitive with candidates who could tap large pools of private money.

But in decisions with slim majorities in 2008 and 2011, the Supreme Court said these laws were unfair because they somehow “penalized” the candidates with greater resources. Since the Court’s decisions, participation in public financing programs in Arizona, the subject of the 2011 ruling, and Maine, which had a similar provision, has dropped by half and a third respectively, and the success rate of self-funding millionaire congressional candidates hasjumped from 12 to 20 percent.

Super PACs, which can raise unlimited money but only spend those funds on activities that are allegedly independent of a candidate’s campaign, have become one of the most powerful vehicles for election spending. But six years ago, they didn’t even exist. That’s because there were limits on how much a donor could give a PAC, no matter how they spent their money.

That all changed with Citizens United, when the Court reasoned that as long as the expenditures are independent of a candidate, there’s no risk of corruption. Only two months later, a lower court followed the Supreme Court’s logic and ruled that there’s no need for contribution limits if a PAC only spends independently of a candidate. Thus, today’s super PAC was born. From 2010 to 2014, super PACs spent more than $1 billion, and more than $600 million of that came from just 195 donors and their spouses. And the failure to enforce the “independence” rule means that super PACs often function effectively as arms of candidates’ campaigns.

2014’s McCutcheon was the most recent ruling to stymie longstanding limits on election spending. Before that decision, one person couldn’t give more than $123,000 directly to all candidates and parties combined in a single election cycle. That limit prevented the wealthiest from having outsized influence, and ensured donors could not easily circumvent contribution limits by giving money to parties and candidates who could easily shuffle it between then. The Court struck it down in another 5–4 ruling, and today one person can give $5.1 million.

The result was immediate, and striking. In the 7 months between McCutcheonand the 2014 midterm election, almost 700 donors exceeded the old limits.And that December, Congress exploited the decision by creating a handful of new political party accounts that can collect contributions of $100,000 each. Now both major parties are soliciting million-dollar contributions.

A decade ago, the campaign finance system was far from perfect, but ordinary citizens had a stronger voice, could more easily run for office, and were better informed about the special interests supporting each candidate. The series of 5–4 Supreme Court decisions beginning in 2007 have gutted that system. Today’s status quo is not the result of some inescapable or long-standing reading of the First Amendment. The reality is that one vote on the Court is all that stands between us and the creation of a system that values average citizens’ voices and election integrity.