5 Things to Know About the Wisconsin Partisan Gerrymandering Case

With Gill v. Whitford, the U.S. Supreme Court has taken the most important case in decades dealing with how Americans are represented in Congress and state legislatures.

In the next few weeks, the Supreme Court will be considering whether to hear Gill v. Whitford, a major partisan gerrymandering case out of Wisconsin. Here’s what you need to know.

1. What’s Gill v. Whitford about?

Wisconsin is asking the Supreme Court to overturn a decision striking down the 2011 redistricting plan for the lower house of the Wisconsin state assembly as a partisan gerrymander.

The Wisconsin voters who brought the case challenged the plan under the First and Fourteenth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution and, in late 2016, won at trial — the first time in over three decades that a map has been struck down as a partisan gerrymander. The lower court ruled that the plan was “an aggressive partisan gerrymander” that locked in a Republican majority in the state assembly under “any likely electoral scenario.”

If the Supreme Court agrees to hear the case (it would be argued this fall), it will be the first time the high court has considered the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering in more than a decade. The case could have major implications for redistricting because, thus far, the Supreme Court has not been able to agree on a standard for deciding when a map goes too far. The Wisconsin case could at last give it that opportunity.

2. What makes the gerrymander in Wisconsin especially bad?

Gerrymandering comes in many varieties, but the kind of gerrymandering that took place this decade in Wisconsin (and a handful of other states) is among the worst. This kind of aggressive gerrymandering doesn’t just pre-determine electoral results, but also locks in a disproportionate and unfair advantage for one party over the other — making maps unresponsive to voters in individual districts and deeply unrepresentative of the electorate as a whole.

At a statewide level, Wisconsin is a quintessential battleground where races are often decided by only a few percentage points. Contrast that to the state assembly map the Republicans drew: In 2012, they won 60 of the 99 seats in the Wisconsin Assembly despite winning only 48.6% of the two-party state-wide vote; in 2014, they won 63 seats with only 52% of the state-wide vote.

This is an odd outcome for a state like Wisconsin, where statewide elections are very close, and voters for both major parties are fairly evenly spread across the state. Voters in Wisconsin, like voters in battleground states in general, are not starkly clustered by party. For example, there are substantial pockets of Democratic voters in places like Vernon County and other rural and small towns, where Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton nearly evenly split the vote. The fact that Wisconsin’s Legislature doesn’t reflect this political diversity is, in large part, intentional.

The same sort of aggressive gerrymandering has distorted the U.S. Congress as well. According to a Brennan Center study, these “extreme maps” account for 16 to 17 Republican seats in the current Congress, a sizable portion of the 24 seats Democrats would need to take back the House.

3. Why is it urgent that the Supreme Court take action against partisan gerrymandering now?

Americans across the political spectrum agree by wide margins that gerrymandering is bad. In 2013, a Harris poll found that seven in ten Americans agreed that those who stand to benefit from drawing electoral lines should not have a say in the way those lines are drawn. This view cut across partisan lines, with 74 percent of Republicans, 73 percent of Democrats, and 71 percent of independents in agreement. Even elected officials agree. Ohio governor John Kasich recently called gerrymandering “the biggest problem we have.” Likewise, President Obama called for an end to gerrymandering in his final State of the Union address in 2016, echoing calls made by President Reagan thirty years earlier.

Unfortunately, gerrymandering is only going to get worse, as legislators and consultants gain access to even more powerful mapping technology and more sophisticated data about voters to make gerrymanders that are even more biased and even more durably so. The same sort of “Big Data” that gives retailers and political campaigns greater insight into people’s behavior will increasingly be used in redistricting as well.

Gerrymandering is one problem voters can’t fix on their own. Citizens can’t just vote the gerrymandering party out of office, because the maps are too heavily skewed. In fact, that’s the whole point of extreme partisan gerrymanders: to insulate the legislative majority from the will of the voters. And while 24 states provide for some form of ballot initiative that could be used to push redistricting reforms, many other states don’t make this option available to voters.

A ruling from the Supreme Court declaring that partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional will, at the very least, create some limits that legislators will have to obey when they draw maps in the future.

4. How can a court tell when partisan gerrymandering has gone too far?

Deeply rooted constitutional values that ensure representation and democratic accountability make clear that extreme gerrymanders are illegal.

There are several types of evidence that can help trial judges tell when these values have been violated. For instance, in Wisconsin, the trial court was able to consult, among other things, emails and documents that showed how the Legislature’s consultants used advanced statistics to evaluate how particular districts they drew would vote and then figure out which maps would advantage Republicans the most. Also in evidence was a string of alternative maps that grew increasingly biased and notes from people involved in the redistricting process recording their understanding of the long-term effects of the maps they chose to use. Additionally, Courts can look at the features of a state’s mapping process and political climate. For example, when a single party controls the redistricting process, it has a unique opportunity to create extreme maps.

The courts will also have the benefit of evidence in the form of social science measures that scholars have developed over the last decade to help them identify when maps have significant, intentional bias. The good news is that although these tests approach the issue in slightly different ways they all flag the same handful of problem state. The task for the Supreme Court won’t be to decide which of these tests courts must use. Trial courts can and should weigh a broad variety of evidence as they do in all kinds of cases, and make judgments about the value of expert evidence as they do in many settings.

5. How many other maps could be affected by a ruling in the Wisconsin case?

A ruling for the plaintiffs in the Wisconsin case would put in place an important limitation ahead of the next round of redistricting in 2021.

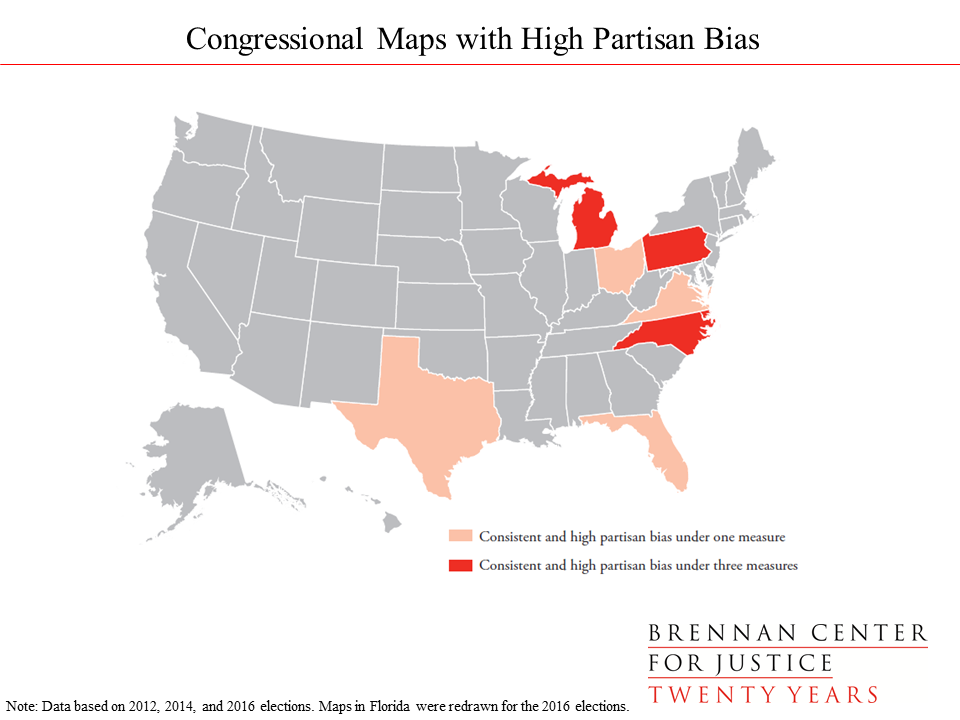

In the short-term, it could set the stage for challenges to around half a dozen congressional maps that exhibit extreme partisan bias.

Research by University of Sydney professor Simon Jackman, likewise, suggests that legislative maps in under a dozen states could be susceptible to challenge for extreme partisan bias.

It’s probably not surprising that, with a couple of exceptions, the states with the worst bias were ones where a single party controlled all the levers in the redistricting process, though Florida’s maps were redrawn in 2016 under court supervision to sharply reduce bias. Exceptions are New York and Virginia, where the party being adversely affected had the power to block adoption of the biased map but did not do so.

By contrast, maps drawn by commissions, courts, and, with a couple of exceptions, split control legislatures did not exhibit statistically significant partisan bias.