Ten states now have unprecedented restrictive voter ID laws. Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin all require citizens to produce specific types of government-issued photo identification before they can cast a vote that will count. Legal precedent requires these states to provide free photo ID to eligible voters who do not have one. Unfortunately, these free IDs are not equally accessible to all voters. This report is the first comprehensive assessment of the difficulties that eligible voters face in obtaining free photo ID.

Executive Summary

Ten states now have unprecedented restrictive voter ID laws. Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin all require citizens to produce specific types of government-issued photo identification before they can cast a vote that will count. Legal precedent requires these states to provide free photo ID to eligible voters who do not have one.

Unfortunately, these free IDs are not equally accessible to all voters. This report is the first comprehensive assessment of the difficulties that eligible voters face in obtaining free photo ID.

The 11 percent of eligible voters who lack the required photo ID must travel to a designated government office to obtain one. Yet many citizens will have trouble making this trip. In the 10 states with restrictive voter ID laws:

- Nearly 500,000 eligible voters do not have access to a vehicle and live more than 10 miles from the nearest state ID-issuing office open more than two days a week. Many of them live in rural areas with dwindling public transportation options.

- More than 10 million eligible voters live more than 10 miles from their nearest state ID-issuing office open more than two days a week.

- 1.2 million eligible black voters and 500,000 eligible Hispanic voters live more than 10 miles from their nearest ID-issuing office open more than two days a week. People of color are more likely to be disenfranchised by these laws since they are less likely to have photo ID than the general population.

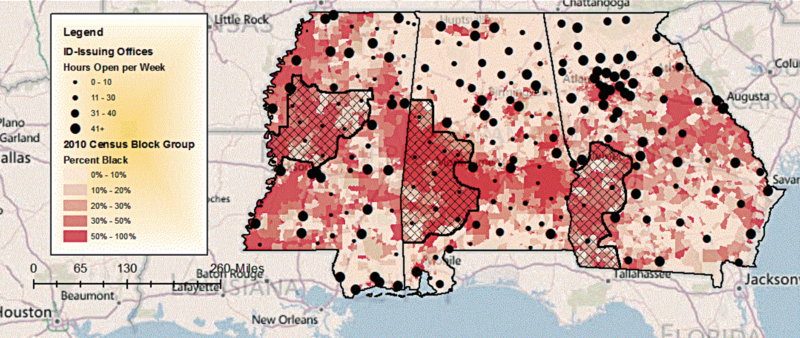

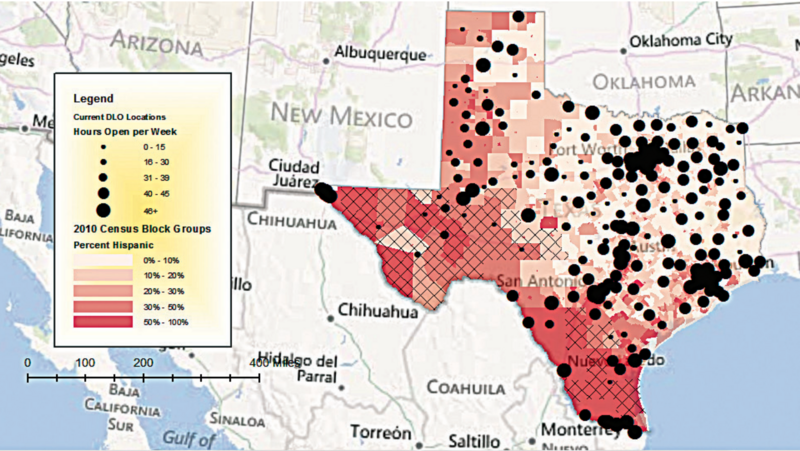

- Many ID-issuing offices maintain limited business hours. For example, the office in Sauk City, Wisconsin is open only on the fifth Wednesday of any month. But only four months in 2012 — February, May, August, and October — have five Wednesdays. In other states — Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Texas — many part-time ID-issuing offices are in the rural regions with the highest concentrations of people of color and people in poverty.

More than 1 million eligible voters in these states fall below the federal poverty line and live more than 10 miles from their nearest ID-issuing office open more than two days a week. These voters may be particularly affected by the significant costs of the documentation required to obtain a photo ID. Birth certificates can cost between $8 and $25. Marriage licenses, required for married women whose birth certificates include a maiden name, can cost between $8 and $20. By comparison, the notorious poll tax — outlawed during the civil rights era — cost $10.64 in current dollars.

The result is plain: Voter ID laws will make it harder for hundreds of thousands of poor Americans to vote. They place a serious burden on a core constitutional right that should be universally available to every American citizen.

This November, restrictive voter ID states will provide 127 electoral votes — nearly half of the 270 needed to win the presidency. Therefore, the ability of eligible citizens without photo ID to obtain one could have a major influence on the outcome of the 2012 election.

Foreword

“All men are created equal.” This shining vision of political equality, set out in the Declaration of Independence, makes the United States exceptional, two centuries later.

Thus it is wrong to enact laws to make it harder for some Americans to vote — not only wrong, but utterly at odds with our most basic national values. Every eligible citizen should be able to vote. And every citizen should take the responsibility to do so. One person, one vote: no more, no less.

Yet since January 2011, partisans in 19 states have rushed through new laws that cut back on voting rights. In a comprehensive study released last October, the Brennan Center concluded these laws could make it far harder for millions of eligible citizens to vote. Fortunately, the Justice Department, courts, and voters have blocked or blunted many of these laws. Many, but not all. And those who would curb the franchise are fiercely fighting in court, going so far as to insist that the Voting Rights Act is in fact unconstitutional.

Among the most controversial measures are new voter identification laws. They require voters to produce specific government papers, usually with a photo and an expiration date, to cast a ballot. Let’s be clear: Election integrity is vital. The problem is not requiring voter ID, per se — the problem is requiring ID that many voters simply do not have. Study after study confirms that 1 in 10 eligible voters lack these specific government documents.

Federal courts have previously declared that states with restrictive voter ID laws must make the necessary paperwork available for free. Problem solved? Hardly. This report conclusively demonstrates that this promise of free voter ID is a mirage. In the real world, poor voters find shuttered offices, long drives without cars, and with spotty or no bus service, and sometimes prohibitive costs. For these Americans, the promise of our democracy is tangibly distant. It can be measured in miles.

It need not be this way. Once partisan “voting wars” have subsided, we can easily move to modernize our ramshackle voter registration system. Using digital technology, states can assure that every eligible voter is on the rolls. That would add millions to the rolls, cost less, and curb the potential for fraud.

Meanwhile, we face a critical national election that may be marred by vast numbers of Americans effectively blocked from the vote. We can and must make sure that the reality of 2012 does not repudiate the civic creed first articulated in 1776.

Michael Waldman

President, Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law

July 2012

Voter ID Maps

Figure 1: Percentage Black and State Driver’s License Offices, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. The map demonstrates that in the areas with the greatest concentrations of rural black voters, no state driver’s license offices are open more than two days per week. The figure also shows that many of these states’ part-time offices are located in the areas with the highest concentrations of black voters. The crosshatched areas outline the 13 contiguous “black belt” counties in Mississippi, 11 contiguous “black belt” counties in Alabama, and 21 contiguous “black belt” counties in Georgia where all state driver’s license offices are open two days per week or less.

Figure 2: Percentage Hispanic Population and Driver’s License Office Locations, Texas. The map shows that in some areas in Texas with high concentrations of Hispanic voters, there are few or no ID-issuing offices. The map depicts concentrations of the Hispanic voting-age population, by 2010 Census Block Group, together with the number of hours per week each office location is open. The crosshatched areas represent the 32 counties in the U.S.-Mexico border region with few or no ID-issuing offices.