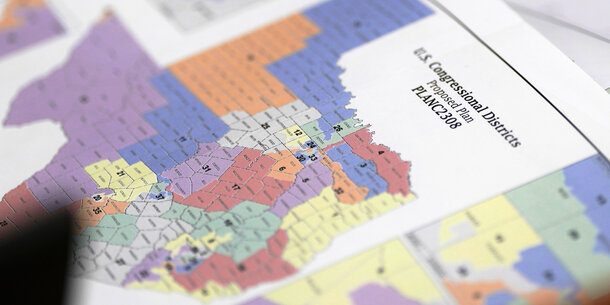

In one of the most important decisions of the term, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s finding that Alabama diluted the electoral power of Black voters in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act when it redrew the state’s seven congressional districts in 2021. The 5–4 decision clears the way for the map to be redrawn in time for the 2024 election to create a second Black congressional district.

Allen v. Milligan, as the case is known, is a welcome departure from the Court’s tendency in recent decades to scale back or even wholly eliminate voting rights protections. Rather than further pare back the Voting Rights Act as many feared, the Milligan decision forcefully rejected Alabama’s attempt to have the Court radically rewrite or strike down a critical voting protection for communities of color. Instead, it reaffirmed the legal framework that has guided courts in Section 2 cases for almost 40 years.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act has long played an indispensable role in protecting against discrimination because it provides voters of color a tool to fight back against systemic exclusion from voting and effective representation. Instead of relying on federal enforcement by the Department of Justice, it creates an opportunity for minority communities to tell their own stories in court and challenge policies that limit their access to the ballot and legislative decision-making power. Section 2’s guarantees apply nationwide and ensure a baseline of fairness at all levels of government — congressional, state legislative, county commission, city council, school board, and judicial districts and all other electoral systems must operate to provide all voters an equal opportunity to participate in the political process and to elect candidates of choice.

Since the Supreme Court adopted it in 1986, Section 2’s framework has helped communities of color pry the door open to political power. After the 1990 census, for example, five Southern states drew congressional maps that enabled Black and Latino communities to elect their preferred candidates for the first time. Yet in many ways, the impact on representation for communities of color at the local level has been even more profound.

As the Milligan decision affirmed, lawmakers cannot enact electoral policies, including new voting districts, that limit the chances of electoral success for minority voters when compared to other voters. Section 2’s standard focuses on contexts where white voters systematically oppose candidates preferred by minority voters and where the district lines advantage the larger white voting bloc and effectively lock out minority voters. Plaintiffs must also prove that it is possible to draw alternative district lines that avoid such outcomes. In other words, Section 2 looks at the role that race plays within the politics of a particular region and whether districting choices in combination with such voting patterns have the effect of limiting political opportunities when viable alternatives are available.

But this is not the end of the inquiry: a successful Section 2 claim must also demonstrate that other circumstances intersect with the race dynamics in elections, such as the history of discrimination and ongoing social, economic, and political disparities, as Congress intended. All of these factors are inherently localized and fact-intensive.