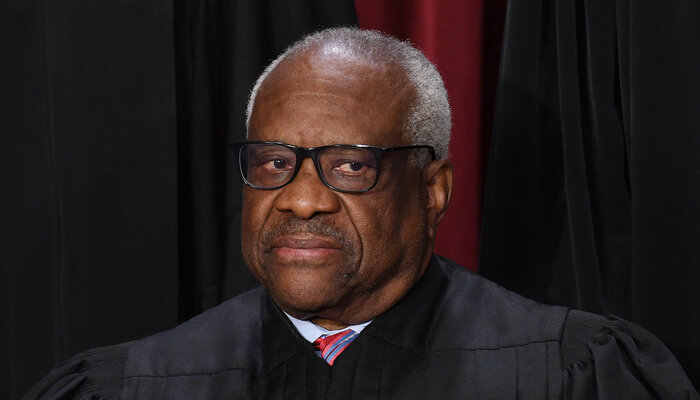

In 2015, Justice Clarence Thomas reported receiving a bust of Frederick Douglass, which he valued at $6,484.12. It was the last of many gifts the justice disclosed from his billionaire friend Harlan Crow. But Crow’s favors to Thomas — such as private jet travel, luxury accommodations, large donations in his honor, favorable real estate transactions, and tuition payments — did not end in 2015. They continued for years without disclosure, according to reporting by ProPublica.

Thomas is not the only one who has come under fire for failing to disclose gifts. ProPublica exposed Justice Samuel Alito’s failure to disclose a 2008 Alaskan fishing trip at the expense of hedge fund billionaire Paul Singer, who also treated Justice Antonin Scalia to similar adventures.

These revelations come at a moment of weakness for the Supreme Court, but they are nothing new. Justices Scalia and Neil Gorsuch faced disclosure scandals. Other justices initially failed to make required disclosures but later corrected the record. In 2016, Justice Sonia Sotomayor didn’t disclose transportation and lodging from various law schools, but she amended her records in 2021. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg amended her disclosure documents in 2017 to include a $4,500 opera costume. All these justices escaped punishment.

Both Thomas and Alito have denied wrongdoing in the current controversies — Alito in a Wall Street Journal op-ed and Thomas in a brief statement. Their defenses are a subject of debate, even among disclosure experts.

These disputes expose the Supreme Court’s unique and complicated relationship with financial disclosure laws. Unlike other federal officials and even federal judges, Supreme Court justices have more leeway and privileges when it comes to what they are legally required to disclose and how they do so. Several justices appear to have exploited their special status, raising important questions about the nature and scope of disclosure laws.

When did financial disclosure laws begin?

Political campaigns have been subject to disclosure law requirements since 1910, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that Congress applied personal financial disclosure rules to federal officials.

The Watergate scandal prompted a new effort for institutional ethics reform in Congress, resulting in, among other things, the Ethics in Government Act of 1978. The law established financial interest reporting requirements for high-level government officials, including Supreme Court justices, and the responsibility to make these documents available to the public. It also gave the public new expectations for the ethical behavior of their leaders. From defining values of what was appropriate for an official to accept as a gift to establishing the Office of Government Ethics, the ethics law established clear-cut rules for financial behavior and consequences for violations. A decade later, the Ethics Reform Act of 1989 expanded those requirements.

What must be disclosed?

Federal officials subject to disclosure requirements must report income, dividends, most capital gains, significant debts, the purchase or sale of land, and gifts, among other things. In many cases, the disclosure rules are reasonably straightforward. There is, however, a significant exception to the required disclosure of gifts, known as the “personal hospitality clause.”

Do federal disclosure rules apply to Supreme Court justices?

Yes, with an asterisk.

Under the Ethics in Government Act, the Judicial Conference, the administrative body established by Congress to administer the judicial branch, is responsible for obtaining, reviewing, and publishing financial disclosure documents of justices and judges. The law also designates the Judicial Conference as the organization that will promulgate specific interpretations of the statute to ensure that the general requirements in statute (which apply to officials in a variety of different parts of the federal government, who naturally face different ethics issues) address the specific needs of the federal judiciary.

As noted above, the statutory requirements in the Ethics in Government Act apply equally to Supreme Court justices and other federal judges. The justices, however, are not subject to the Judicial Conference’s interpretations of the ethics law — that is, the specific interpretations the Judicial Conference imposes on lower court judges do not apply to the Supreme Court.

The Judicial Conference makes this point in their guidelines (under Section 620.65):

All officers and employees of the judicial branch hold appointive positions. Title III of the Ethics Reform Act of 1989 (5 U.S.C § 7351 and 7353) thus applies to all officers and employees of the judicial branch. However, the Judicial Conference has delegated its administrative and enforcement authority under the Act for officers and employees of the Supreme Court of the United States to the Chief Justice of the United States and for employees of the Federal Judicial Center to its Board. (Emphasis added.)

In 1991, the justices publicly agreed to follow the Judicial Conference interpretations that apply as a matter of law to lower court judges. But, because the justices do so voluntarily rather than by legal obligation, there is a legal grey area. If a justice disagrees with the Judicial Conference’s interpretation of the statute — or, more likely, simply thinks that a Judicial Conference rule doesn’t apply to the specifical financial interest at issue, even if the Judicial Conference or others would disagree — there would be no way for anyone except the chief justice to overrule that decision. This potential gap has been especially apparent when considering how justices have operated when disclosing, or not disclosing, gifts.

What is the “personal hospitality clause”?

The personal hospitality clause is an exception to the gift disclosure rules of the Ethics in Government Act. Sometimes referred to as the “personal hospitality loophole,” it does not require an official, including a federal judge, to disclose gifts of food, lodging, or entertainment “received as personal hospitality of an individual.”

The Judicial Conference outlines specific limits on this exception and mechanisms for punishment if lower court judges stray beyond them. But Supreme Court justices, who are not legally bound by the Judicial Conference’s interpretation, have relied on this clause to justify not disclosing gifts that it appears they would otherwise have to. Justices Alito and Thomas each alluded to this clause in their responses to the ProPublica reports.

In March 2023, the Judicial Conference clarified the definition of personal hospitality in a letter addressed to Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), an advocate for Supreme Court ethics reform. It stated that personal hospitality encompasses:

Hospitality extended for a non-business purpose by an individual, not a corporation or organization, at the personal residence of that individual or his or her family or on property or facilities owned by that individual or his or her family.

The Judicial Conference further noted that the personal hospitality exemption does not apply to transportation. The rules added that the individual extending the hospitality must be the one paying for it, not an entity or other individual. Any gift or favor that is extended at a property owned by a company, even if the individual who is extending the gift wholly or partly owns it, must be disclosed too. This new definition applies to the justices to the extent that the justices have agreed to follow these rules.

Two aspects of these new clarifications demonstrate the issues with the financial disclosures of Clarence Thomas in particular. First, the regulations explicitly state that a personal hospitality gift must come from an individual’s own pocket — not from a company or entity (Crow’s jet is likely owned by an LLC). Second, transportation, e.g., private jet travel or yachting adventures, must be disclosed. If ProPublica’s reporting is accurate, Thomas should amend his financial disclosures to show his travel on Crow’s yacht and plane, as well as any other benefits that Crow did not personally fund.

What is the process of investigating and sanctioning judges who fail to disclose gifts?

If a federal judge is suspected of not properly disclosing their finances, the Judicial Conference has a complaint process. When the failure is unintentional, it appears that the judge is merely required to amend their disclosure. If the process exposes a willful violation, the attorney general may seek civil or criminal penalties.

It’s unclear how many federal judges have been investigated or punished. The Judicial Conference does not appear to make public the existence of investigations or sanctions. Inquiries submitted to the judicial branch in search of those records have reportedly received no response. Investigations are likely to become public only if the attorney general takes action or the case is referred to Congress for impeachment, each of which is an extremely rare occurrence.

• • •

In 2022, President Biden signed into law the Courthouse Ethics and Transparency Act. The act mandated the creation of an online database for the financial disclosure documents of federal judges and Supreme Court justices, bringing greater public transparency. However, the continued public reporting on the justices’ behavior has demonstrated the need for reform beyond increased transparency.

Some members of Congress have recently demanded that the judiciary adopt a wide array of reforms — from more regulations on financial disclosures to the justices implementing their own code of conduct. Some members have gone further, creating legislation to bring about such reforms: Rep. Hank Johnson (D-GA) and Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) reintroduced the Supreme Court Ethics, Recusal, and Transparency Act, and Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) reintroduced the Judicial Ethics and Anti-Corruption Act. Both bills contain ideas for strengthening financial disclosure procedures. It appears that the future of financial disclosure rules for Supreme Court justices will be part of the broader conversation about court reform.

The Brennan Center thanks Professor Stephen Gillers of New York University School of Law and Gabe Roth of Fix the Court for sharing their expertise.