Internal documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit filed by the Brennan Center and Data for Black Lives reveal that for years, Washington, DC, police have used online surveillance tools to monitor people’s social media activity, collect data on individual users and their friend networks, and keep tabs on public protests. The documents provide a window into a secret world of social media surveillance that can chill the free exercise of First Amendment rights.

On the whole, the police departments employing these tools operate almost entirely in the dark, providing little public insight into how they analyze social media data or flag accounts for monitoring. The lack of meaningful guardrails or privacy protections around how and under what circumstances law enforcement can use surveillance tools leaves the public vulnerable to dystopian tracking of their online activities.

While the full scope of DC police’s use of surveillance technologies remains unclear, our review of thousands of pages of documents, including procurement records and emails exchanged with an array of private vendors, reveals that between 2014 and 2022, the Metropolitan Police Department used software from companies including Babel Street, Dataminr, Sprinklr, and Voyager. These vendors’ tools offer a variety of capabilities, though it’s not always clear whether the reality matches the hype.

Babel Street says it generates real-time information by scanning millions of websites and 25 social media platforms. Dataminr, a company affiliated with X (formerly Twitter), claims to detect real-time threats by sifting through unfiltered social media data, including the stream of internal data referred to as X’s “firehose.” In 2020, Dataminr faced fierce blowback for leveraging its access to X’s data to gather information about Black Lives Matter protests for police tracking. Sprinklr markets its ability to use artificial intelligence to analyze social media data. Unlike Sprinklr and Dataminr, which are “alerting” tools, Voyager Labs claims to analyze individuals’ behavior and associations online to predict “extremism.” Together, these software programs rummage through millions of people’s online information and flag ostensible threats for police.

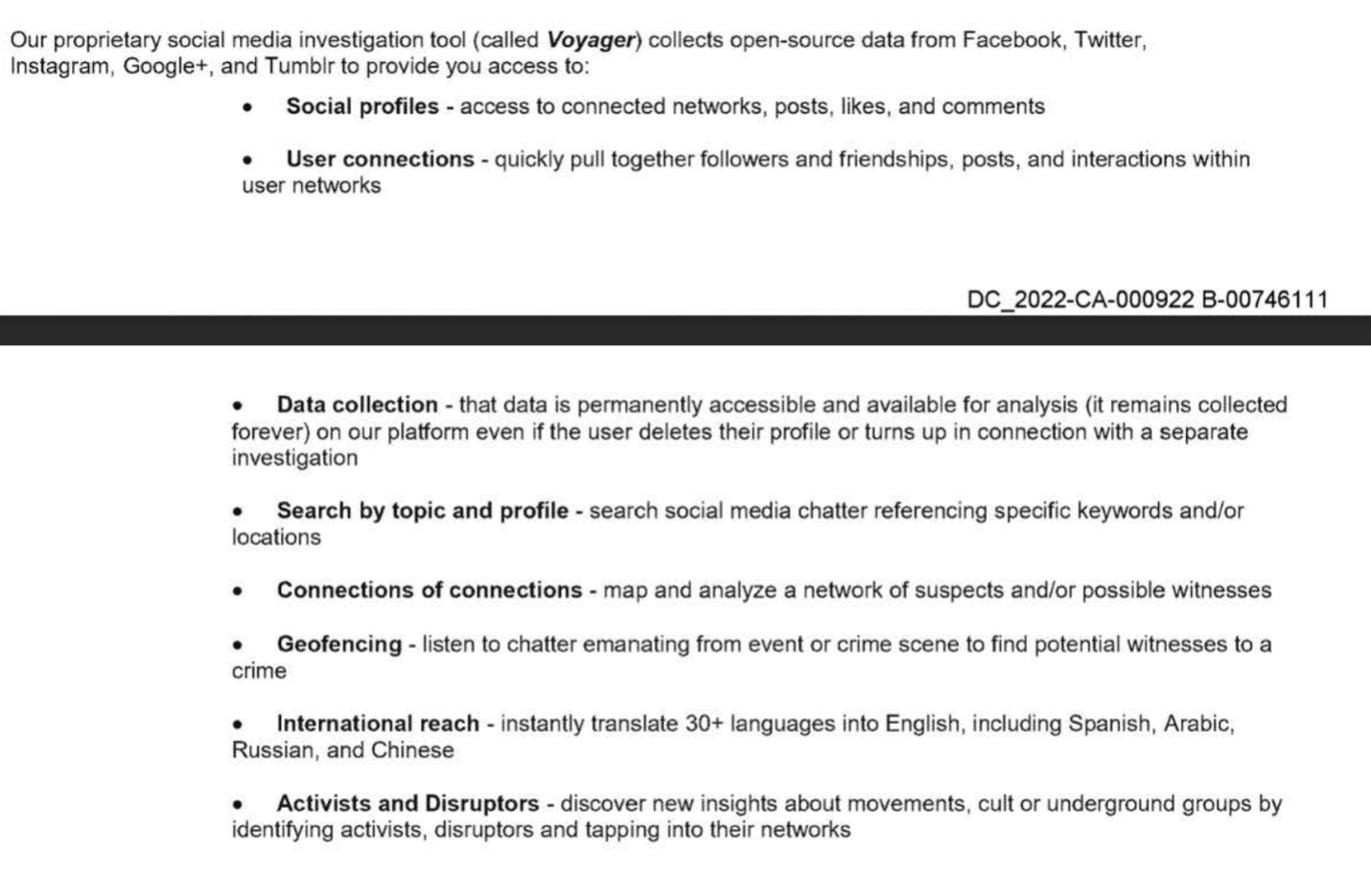

The documents reveal how the companies market their dubious technological capabilities to law enforcement. Over email, Voyager promoted its ability to run keyword searches on social media platforms to generate a list of thought leaders, activists, and “disrupters” and then tap into their networks. The tool can construct a report of social media profiles that includes an analysis of the content of user posts and geolocation data for each post. In addition, Voyager claims that it can analyze “billions of publicly available data points and behavioral indicators from social networks” to flag a person’s interests and assess the strength of their personal relationships.

A brochure for a Voyager program brags that its tool can identify people who could aid in a criminal investigation by searching an arrestee’s social media network for people who may be linked to previous law enforcement searches or are connected to several people of interest. Another document shared via email by a company representative provides an overview of the information Voyager gathers and organizes from people’s social media activity.

DC Metropolitan Police Department

DC Metropolitan Police Department

If Voyager’s claims are true, all of this would allow DC police to build a vast “database of persons of interest” that could include information about ostensibly innocent individuals connected on social media to arrestees, a connection which may not actually tell police anything about their real-life relationships. This data is retained “for the life of the Voyager system,” effectively creating a time machine that enables police to peruse data at their leisure that may have been collected for a very different purpose or is no longer public.

Numerous emails reflect how DC police deploy these powerful tools to track individual organizers. One shows that, in 2015, Babel Street provided the DC Homeland Security and Emergency Management Agency, a fusion center to which the police belong, a list of people who had been present in both Baltimore and Ferguson, Missouri, during protests against police brutality in those cities, as well as people who were connected to those individuals but who had not been physically present in either place. A fusion center analyst then shared the list with DC police department personnel.

DC Metropolitan Police Department

DC Metropolitan Police Department

This list of people flagged by the company included a veteran, a student, and a public school teacher. It is not clear what either the fusion center or the police planned to do with this list, or why Babel Street thought these people were an appropriate target of law enforcement surveillance.

DC police also rely on the tools to monitor peaceful protests. An internal email shows that during President Trump’s inauguration, the department fed Sprinklr a list of terms to track online, including the phrases #Jointheresistance, #ResistTrump, #RefuseFacism, and #Anticapitalist.

DC Metropolitan Police Department

DC Metropolitan Police Department

DC Metropolitan Police Department

DC Metropolitan Police Department

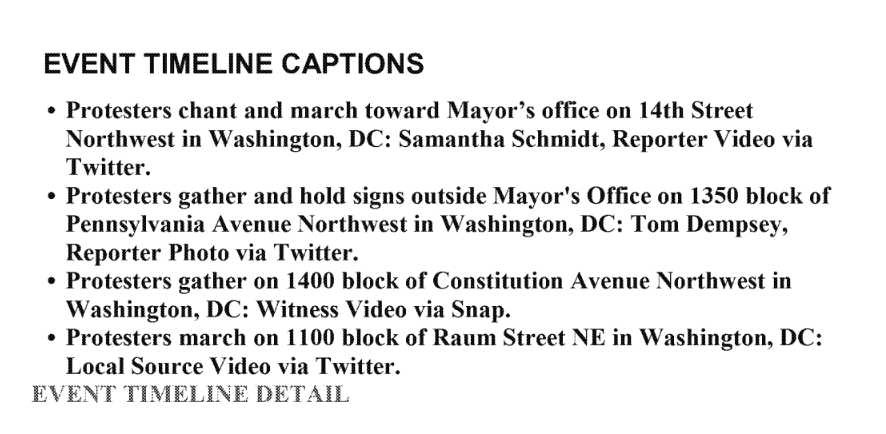

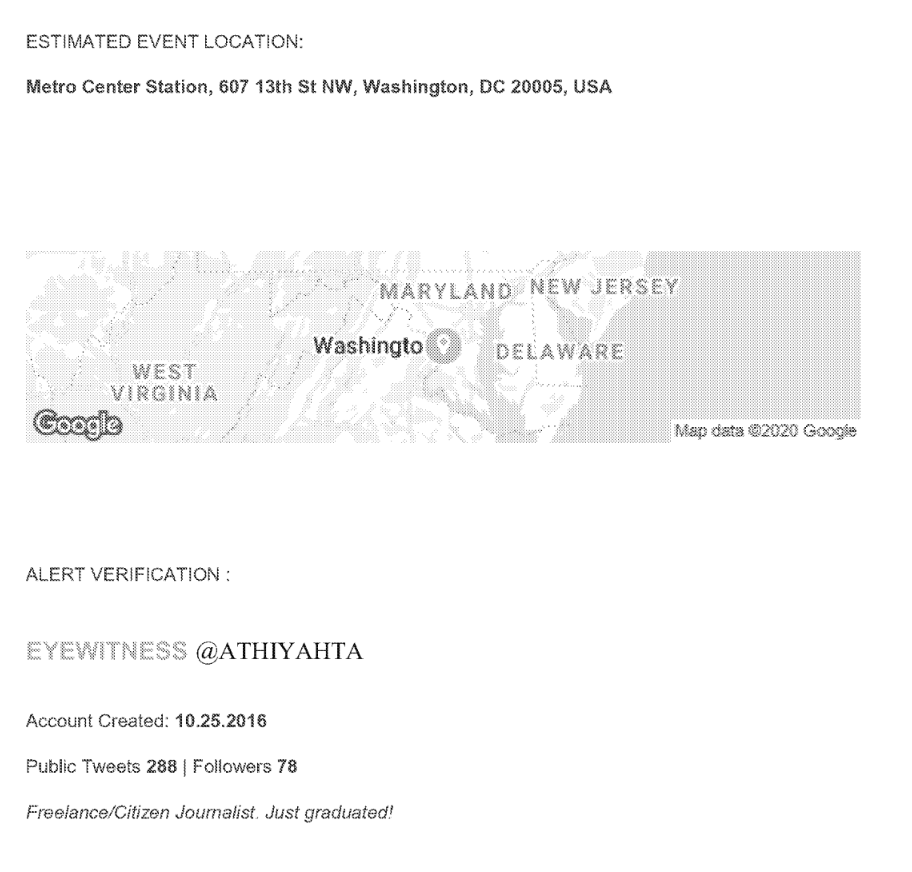

Dataminr sent email alerts — of which we received 160,000 spanning a two-year period from June 4, 2020, to May 20, 2022 — to the police about planned demonstrations and tracked the movements of protests on topics ranging from Covid-19 restrictions to police brutality. In each of these emails, Dataminr provided the social media handle of the person sharing the planned action, their follower count and bio, the location of the protest, and the content of the social media post. Some alerts include event timelines that are created by scanning social media for individual users’ updates, which allow the tool to piece together the movement of protesters. One alert, sent by Dataminr about a planned protest, included both an event timeline and the social media profile of a recent college graduate with fewer than 100 followers, who shared an update about the event.

DC Metropolitan Police Department

DC Metropolitan Police Department

DC Metropolitan Police Department

DC Metropolitan Police Department

In response to high-profile scandals regarding the scale of law enforcement social media monitoring, some social media companies acted to cut off social media monitoring vendors’ access to user data. In a 2016 email, a Voyager sales representative mentioned that “social media networks have cut access to their firehose of data and there is pressure from civil liberties organizations against ‘surveillance’ tools.” The representative then noted that, unlike other tools, Voyager maintains access to data from Facebook, Instagram, and X.

Voyager’s pitch was clearly persuasive. Later that year, a police department employee noted favorably that Voyager “does not depend on social media providers such as Twitter, etc., granting access to their data,” implying that the company is scraping the data instead. This practice is what eventually led Meta to sue Voyager in 2023 for creating 55,000 fake accounts and obtaining information from around 1.2 million user profiles.

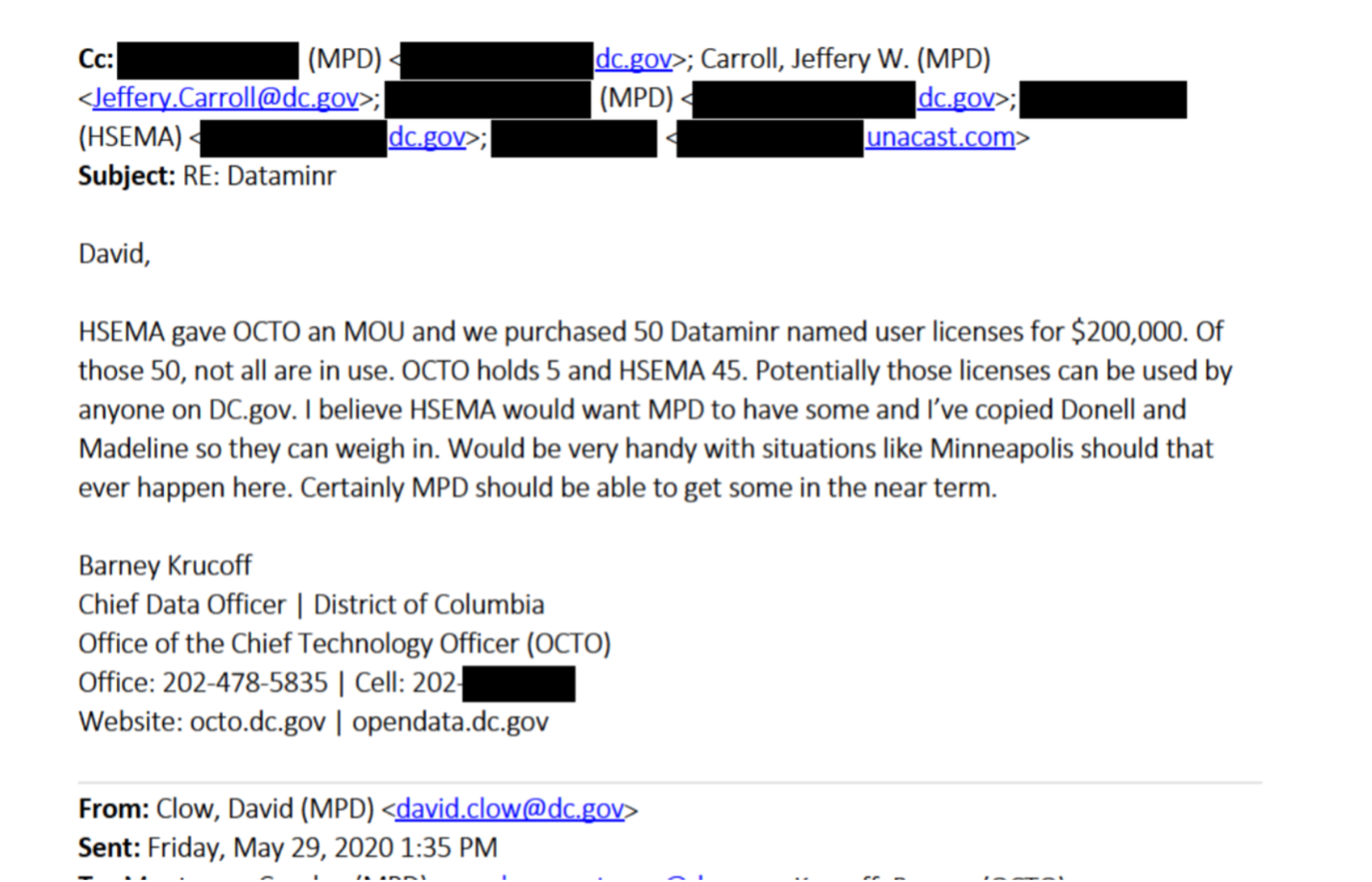

Despite social media platforms’ attempts to rein in these programs, DC police and closely associated agencies have continued to pay tens of thousands of dollars to preserve its access. From 2016 to 2020, the DC fusion center spent almost $175,000 to access Babel Street’s software, which the DC police could access through its agreement with the fusion center. In 2017, the police trialed Sprinklr. The company provided an estimate of $40,000 for a 60-day trial, though it is unclear whether the department paid for the trial. In 2018, the DC police purchased seven annual licenses with Dataminr for $47,950 and spent $1,100 a month for access to another private vendor’s software, including social media searching capabilities. An email from 2020 shows that the District of Columbia’s Office of the Chief Technology Officer purchased 50 Dataminr licenses for $200,000 and that the office provided the police with some of these accounts because they “would be very handy” in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder.

DC Metropolitan Police Department

DC Metropolitan Police Department

As DC police continue to pay for surveillance tools that track peaceful protests and generate lists of activists and their networks, the public deserves full information regarding their use. A review of the documents provided in response to the request by the Brennan Center and Data for Black Lives raises concerns about how law enforcement is deploying these tools to collect personal information, flag people as part of investigations, and monitor First Amendment–protected activities.

So long as the police continue to purchase social media surveillance tools, they must be deployed in a way that promotes public safety without undermining fundamental privacy and First Amendment rights. Departments must commit to adopting commonsense guardrails to prevent misuse and abuse of social media.