As we barrel toward 2020 and a momentous presidential election, the need to replace antiquated voting equipment has become increasingly urgent. This is true for at least two reasons. First, older systems are more likely to fail and are increasingly difficult to maintain. In the 2018 midterm election, old and malfunctioning voting machines across the country led to long lines at the polls, leaving voters frustrated – and, in some cases, causing them to leave before casting a ballot.[1]

Second, older systems are less likely to have the kind of security features we expect of voting machines today. Chris Krebs, head of cybersecurity at the Department of Homeland Security has warned that the 2020 election is “the big game” for adversaries looking to attack American democracy. [2] Meanwhile, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) recently noted that machines that do not produce a printout of a voter’s selections that can be verified by the voter and used in audits – should be “removed from service as soon as possible,” to ensure the security and integrity of American elections. [3]

This report is an update to earlier analyses conducted by the Brennan Center in September 2015 and March 2018, which examined the state of voting machines and election security in the United States.[4] Since our last update, Congress provided $380 million in Help America Vote Act (HAVA) funds to help states to bolster their election security. For the most part, states have used this money for critical security measures. For instance, the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) has reported that states will use $136 million of this funding to strengthen election cybersecurity, $103 million to purchase new voting equipment, and $21 million to improve post-election audits.[5] But this only scratches the surface of investments that are needed in the coming years. As we noted when the grants were issued, the way the money was distributed means it was insufficient to replace the vast majority of the most vulnerable machines before the 2020 election.[6]

Below we detail data – culled from a recent Brennan Center survey of election officials, plus the Brennan Center’s own research and monitoring of the current state of election technology and security practices – to provide a snapshot of the current state of voting technology in the United States, as well as to detail critical steps that should be taken to increase the security and reliability of American elections ahead of 2020.

- Voting Machines Aging Out of Use

This winter Brennan Center surveyed election officials around the country on their need to replace their voting machines. Local election officials in 254 jurisdictions across 37 states told us they plan to purchase new voting equipment in the near future.[7] For some, the need to make these replacements was extremely urgent: 121 officials in 31 states told us they must replace their equipment before the 2020 election.[8] Two-thirds of these officials reported that they do not have the adequate funds to do so, even after the distribution of additional HAVA funds from Congress.

The need to replace this equipment is largely related to the fact that voting machines across the country are “aging out,” as more than one election official told us.[9] For instance, 45 states are currently using voting equipment that is no longer manufactured (in the case of New York and Rhode Island, this only applies to accessible ballot marking devices that are not used to count votes).[10] Jurisdictions that use machines that are no longer produced face challenges when trying to maintain them, including difficulty finding replacement parts. In an interview with the Brennan Center, Rokey Suleman, former elections director for Richland County, South Carolina, expressed feeling “lucky to be able get spare parts” for the machines in his county, which had been discontinued, but noted that it’s “not going to keep being that way in the near future.” [11]

And even when election officials can get spare parts, for those with paperless equipment, it might not make sense to keep pouring money into an antiquated system. “For years, my voters have been asking for a system that provides a paper trail. I don’t want to spend money on something that isn’t in line with where we want go as a county,” said Dana Debeauvoir, county clerk for Travis County, Texas. [12]

Many of these machines are reaching the end of their lifespan. Election officials in 40 states told us they are using machines that are at least a decade old this year.[13] The lifespan of electronic voting machines can vary, but experts agree that systems over a decade old are more likely to need to be replaced for security and reliability reasons. Suleman compared maintaining old voting equipment to maintaining an old car. “When a car starts aging, you need to change the radiator fluid, the battery, the fan belt. We are driving the same car in 2019 that we were driving in 2004, and the maintenance costs are mounting up.”[14] He also noted that South Carolina’s systems run on software that was developed decades ago, including Windows XP. Too often, vendors no longer write security patches for such software, leaving machines more vulnerable to cyberattacks. [15]

Finally, a disproportionate number of these old systems have no voter verified paper backup, something that NAS, the intelligence committees in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, as well as security experts around the country, have argued is an unnecessary security risk.[16] In 2019, 12 states still use paperless electronic machines as the primary polling place equipment in at least some counties and towns (Delaware, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas). Four (Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, and South Carolina) continue to use such systems statewide.[17]

- Prioritizing Paper Ballots (With Some Exceptions)

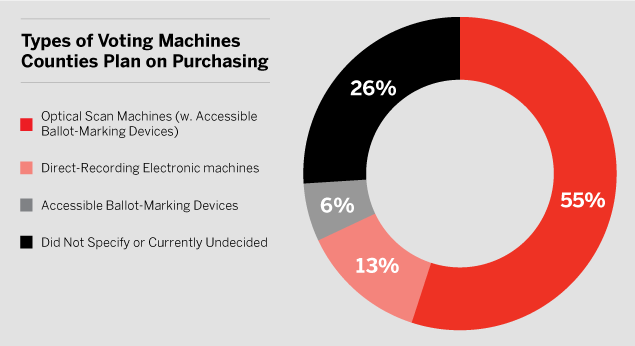

Almost every election official who responded that they planned on replacing voting equipment soon stated that their hope was to find new machines that produce voter-verified paper backups that could be used in a recount or audit (this includes jurisdictions in 9 of the 12 states using paperless voting equipment; election officials in the three remaining states, Indiana, Louisiana and New Jersey, did not respond to our survey). Of these 254 local jurisdictions, roughly half (139 jurisdictions) plan on purchasing optical scan machines with accessible ballot-marking devices, 13 percent (33 jurisdictions) plan on purchasing DREs (direct-recording electronic voting machines) with a paper trail, and 6 percent (15 jurisdictions) plan on purchasing ballot-marking devices only. The rest did not specify what equipment they are planning on purchasing or are currently undecided.

While only one local election official (from Texas) responded that he hoped to replace his current paperless system with another paperless system, it is clear he is not entirely alone. Despite the recent attention to election security, and repeated warnings by security experts that voting machines should have a voter-verified paper backup, several counties in Texas have purchased machines without a paper trail since 2016.[18]

Suleman expressed dismay at the idea of continuing to purchase paperless equipment. “Why? Why? Especially with heightened sense of paranoia about outside influence into our election systems. We need to have a way to independently validate voters’ intent away from tabulation equipment. I don’t understand how any election official could really consider a totally paperless system in this day and age.”[19] Shantiel Soeder, election and compliance administrator at Ohio’s Cuyahoga County Board of Elections, shared Suleman’s sentiment. “At the end of the day, we have that ballot that we can always go back to. We still find it important to print out receipts for other transactions in our lives. To have absolutely no paper, it’s almost irresponsible. These are people’s votes!”[20]

Six of the 12 states (Delaware, Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania) that still use paperless electronic machines as the primary polling place equipment in at least some jurisdictions have either passed laws or taken other actions to replace those systems with machines that produce a paper backup. Of those, Delaware appears to have secured enough funds to replace its systems this year.[21] New Jersey and Pennsylvania have yet to secure sufficient funding for such purchases.[22] In Georgia and South Carolina, state election officials have requested funds to do so, and those requests are currently being considered by the state legislatures.[23] Louisiana appears to have secured sufficient funds to replace equipment, but its purchase of new machines is stalled due to a controversy over how the state conducted its bidding process.[24]

Of the remaining six states (Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Texas), Kentucky Secretary of State Alison Lundergan Grimes and the state board of elections have called for replacement of all paperless systems, but do not yet have sufficient funds to do so.[25] Kansas recently prohibited counties from purchasing new DREs that do not produce a paper record and implemented a post-election manual audit requirement this year, but has not yet forced counties continuing to use paperless machines to replace them.[26] Indiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Texas do not appear to be taking steps to replace their paperless equipment before 2020, with Indiana’s Secretary of State Connie Lawson stating that the federal money provided last year was insufficient to replace the state’s machines.[27]

- Progress on Post-Election Audits

Cybersecurity experts agree that routine and robust post-election audits of voter-verified paper records are necessary to ensure that the paper records provide real value. Currently, 22 states and the District of Columbia conduct post-election audits before certifying their election results.[28] The Brennan Center, along with many other election integrity groups and security experts, has urged the more widespread adoption of risk-limiting audits (RLAs), considered the “gold standard” of post-election audits.

RLAs employ statistical models to provide a high level of confidence that a software hack or bug did not produce the wrong outcome. Effective RLAs can go a long way toward identifying any potential inaccuracy in election results, whether accidental or purposeful.[29]

As of February 2019, only two states require RLAs: Colorado and Rhode Island. Two additional ones, Ohio and Washington, allow election officials to select them from a list of audit types that meet the state’s post-election audit requirement.[30] A bill to require RLAs is pending in New York, while Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina, and New Jersey are all considering bills that would expressly authorize either pilots or immediate implementation of RLAs.[31] Several more jurisdictions have recently piloted these post-election audits, and even more intend do so in 2019. This includes election jurisdictions in Michigan, Rhode Island, Virginia, Indiana, and California.[32] Both Rhode Island and New Jersey used the 2018 Congressional HAVA grants to pilot RLAs in the last few months.[33]

- Additional Election Security Priorities

In addition to replacing voting machines, election officials expressed the need for additional funding for other security related measures. A top funding priority for election officials was the hiring of more IT support staff, particularly at the local level. County election officials are literally on the front-lines defending our election equipment, yet they are frequently the least well-resourced offices. Richards Rydecki, assistant administrator for the Wisconsin Elections Commission, told us that one of challenges Wisconsin faces with being so decentralized is the varying levels of county and municipal resources. “Some of our counties might have only one county clerk and one more person working on elections. And most have very limited IT support. We would like to explore a program to provide contracted IT support on a regional basis.”[34]

Dana Debeauvoir was one of several officials who noted that additional funds should be used by jurisdictions around the country to purchase Albert sensors, a network monitor that alerts election officials when unusual activity is going on that may be putting their data at risk.[35] As Debeauvoir puts it, it’s a matter of learning how to practice “good computer hygiene.”

Other items that election officials mentioned include providing more training for their staff (cybersecurity, procurement, etc.), strengthening the physical security of their storage locations and polling places (security cameras, better inventory management, etc.) and putting in place robust post-election audits.[36]

The authors thank the U.S. Vote Foundation for providing critical support for our survey of election officials, as well as the election officials who responded to the survey and agreed to be interviewed for this analysis, and our Brennan Center colleagues, Jeanne Park and Lorraine Cademartori, for their careful review and edits. Any errors should be attributed to the authors.