In recent years, support for the Equal Rights Amendment (or ERA) has seemingly been a partisan affair, with Democrats largely in favor of amending the Constitution to guarantee equal rights for women and Republicans largely opposed. Proposed by Congress nearly a half century ago with broad bipartisan support, the ERA became a casualty of the Republican Party’s rightward ideological shift in the 1970s. A dramatic drop in GOP support ultimately doomed the measure. But now, in the face of a surprising new push to ratify the amendment at long last, could the GOP be warming up to the ERA once again?

The Equal Rights Amendment was first proposed in 1923, three years after the 19th Amendment guaranteed women the right to vote. While the text of the ERA varied over the decades, the goal remained the same: ensuring that women and men have equal rights under the law. In 1940, the Republican Party became the first major party to endorse the amendment in its platform. Through 1976, the GOP continued to call for the ratification of the ERA in every presidential election cycle save two: 1964 and 1968.

Over those decades, prominent Republicans across the country, including three presidents, pledged their support for the measure. Dwight Eisenhower became the first president to advocate for the ERA’s passage in a 1957 message to Congress. Richard Nixon also endorsed the ERA throughout his career, from his early years as a senator to his two terms as Eisenhower’s vice president to his five years in the White House. In a letter to then-Republican Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott sent days before a key vote, Nixon wrote that “throughout twenty-one years I have not altered my belief that equal rights for women warrant a Constitutional guarantee – and I therefore continue to favor the enactment of the Constitutional Amendment to achieve this goal.” Another Republican, Gerald Ford, played a crucial role in the ERA’s passage during his tenure as house minority leader, and he continued to voice his support for ratification during his brief tenure in the Oval Office.

In March 1972, Congress passed its resolution sending the ERA to the states for ratification with strong bipartisan support. In the House, 78 percent of Republican members voted in favor; 84 percent of Senate Republicans also supported the measure. This strong bipartisan consensus was also evident in the early state ratification process. Within a year, the ERA won the support of 30 of the 38 states needed to ratify. One-third of those states had legislatures fully controlled by Republicans. In another five, the GOP either controlled one house of the legislature or shared control with Democrats.[1] But then, momentum slowed. Conservative activists allied with the emerging religious right and launched an effective campaign to stop the ERA in its tracks, persuading five states to rescind their support.[2] Not surprisingly, Republican politicians took note.

A clear shift in the GOP’s stance can be found in Congress’ 1978 vote to extend the deadline for ratification. Like most amendments proposed in the 20th century, the Equal Rights Amendment included a seven-year time limit for ratification. Between 1973 and 1977, only five additional states approved the measure, leaving it three states short of the total needed to ratify (with the validity of the five state rescissions unresolved). ERA proponents lobbied for more time. But when Congress acted to extend the deadline, GOP support dropped sharply. While the Senate supported the extension by a vote of 60–36, a bare majority of Republicans voted no. And in the House of Representatives, which voted for the extension by the comfortable margin of 233–189, 70 percent of Republicans opposed it.

By the presidential election of 1980, with Ronald Reagan as the party’s new standard bearer, the GOP’s center of gravity continued to move increasingly rightward. That year, the GOP changed its party platform to “acknowledge the legitimate efforts of those who support or oppose ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment.” It was the last time that the ERA was ever mentioned in the party’s platform.

When the extended deadline for ratification expired in March 1982, ERA proponents conceded defeat. But in March 2017, a full 35 years after the lapsed deadline, Nevada unexpectedly ratified the amendment, rekindling a national debate over the viability of the ERA. Since then, the measure has won the support of the Illinois legislature too.

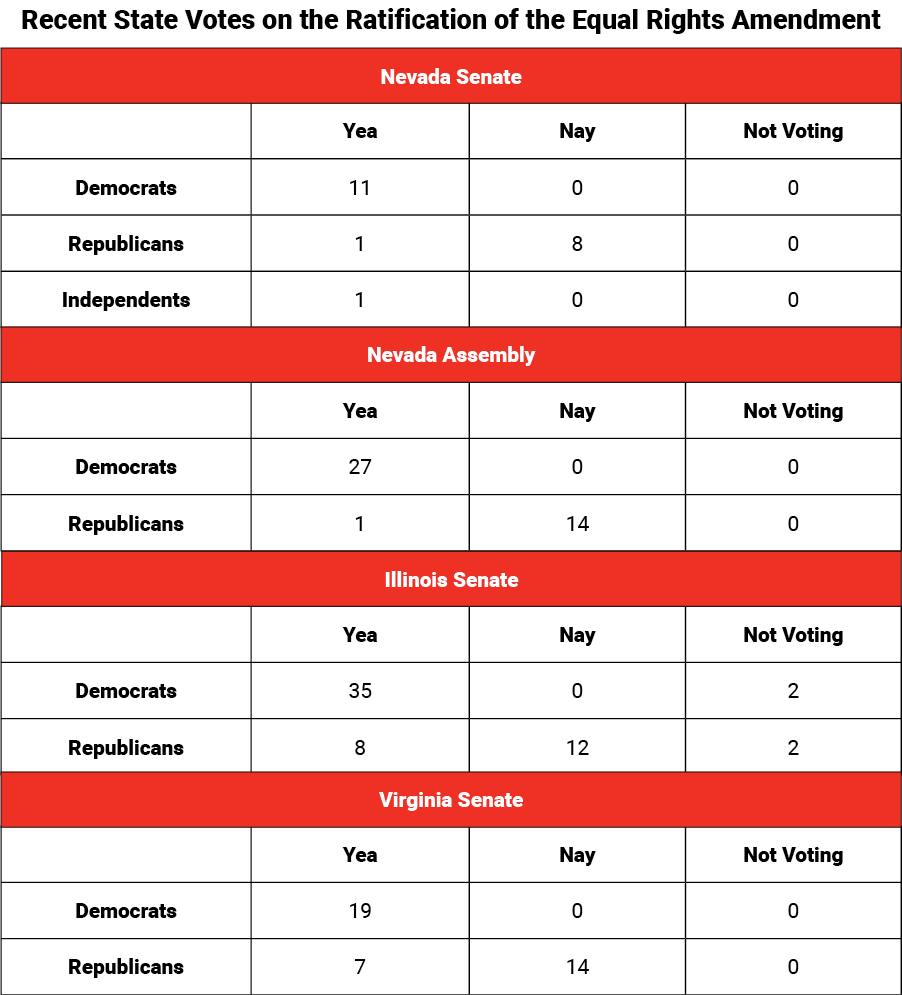

The March 2017 ratification vote in Nevada was a mostly party-line affair, with only one Republican joining unanimous Democrats in either chamber. But there was a significant uptick in GOP support in the Illinois vote one year later, thanks in part to the efforts of State Representative Steve Andersson, a conservative Republican who energetically supported ratification. When the Illinois Senate voted to ratify in April 2018, eight of 13 GOP senators – a solid majority – joined their Democratic counterparts. In the May 2018 House vote that followed, ten of 51 GOP members – nearly one-fifth of the caucus – voted with Democrats to make the Land of Lincoln the 37th state to ratify.

The Nevada and Illinois legislatures are both controlled by Democrats, who had the power to set the agenda. But this year, following a midterm election that saw a record number of female candidates running for office and winning, the ERA advanced – for the first time since the early 1970s – in a legislative chamber controlled by Republicans. The GOP-controlled Virginia Senate voted to ratify in January, with seven of 21 Republicans joining the Democratic minority. Glen Sturtevant, a Republican state senator, was a key sponsor. While the bill failed to advance in the state’s House of Delegates, other efforts have sprung up in Republican-controlled legislatures in Georgia and South Carolina.

There are a number of reasons why Republican lawmakers today may be increasingly willing to support the ERA. First, as election results from 2017 and 2018 revealed a sharply widening gender gap benefiting Democratic candidates, especially among young women, support for the ERA is a good way to appeal to female voters. It’s worth noting that 90 percent of Republicans support the amendment, according to a 2016 poll commissioned by the ERA Coalition. Second, the anti-ERA rhetoric that stalled the ratification campaign of the 1970s may have lost its force. Many of the “dangers” that the STOP ERA campaigners warned about, from women in combat to same-sex marriage to unisex bathrooms, have come to pass without the ERA. Third, at a time of resurgent women’s activism, from the women’s marches to the #MeToo movement, the goal of enshrining gender equality in the Constitution strongly resonates with women (and men). Rep. Andersson, in his remarks at a November 2018 Brennan Center symposium on the ERA, noted that a key Republican legislator switched his vote because “[his] daughter never forgave him for voting against gay marriage” and he “wasn’t going to make that mistake again.”

The political climate around the ERA isn’t just changing in state capitals. We are also seeing green shoots of bipartisan interest in Congress. In January, Sens. Ben Cardin (D-MD) and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) introduced Senate Joint Resolution 6, a bipartisan bill to eliminate the ERA’s ratification deadline. While many supporters of the amendment say that the post-deadline ratifications are valid, it will surely be contested and the decision will ultimately rest with Congress and the courts. But this bipartisan measure sends a powerful signal to the 13 states that have not yet ratified. Upon the release of SJR 6, the two senators penned a Washington Post op-ed, in which they insist that gender equality “is not a partisan issue but one of universal human rights.” As we’ve seen across the country from Illinois to Virginia, it looks like more and more Republicans are getting on board with that message.

(Image: Chip Somodevilla/Getty)

[1] Republicans had control of both houses in New Hampshire, Delaware, Iowa, Idaho, Kansas, Colorado, New York, Wyoming, Vermont, Connecticut. They controlled one house of the legislature in New Jersey and Wisconsin. They were tied for control with Democrats in one house of the legislature in Alaska, Michigan, and South Dakota.

[2] The states that voted to rescind their ratifications were Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, Kentucky, and South Dakota.