In late July, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence released its report on the Russian government’s attacks on America’s election infrastructure.[1] While the report offered dozens of recommendations related to vast and varied election systems in the United States (from voter registration databases to election night reporting), it pointedly noted that there was an urgent need to secure the nation’s voting systems in particular.[2] Among the two most important recommendations made were that states should (1) replace outdated and vulnerable voting systems with “at minimum… a voter-verified paper trail,” and (2) adopt statistically sound audits. These recommendations are not new and have been consistently made by experts since long before the 2016 election.[3]

Last year, Congress provided $380 million to states to help with upgrades, but it wasn’t enough. This analysis, six months ahead of the first primary for 2020, examines the significant progress we’ve made in these two areas since 2016, and it catalogs the important and necessary work that is left to be done.

I. Replacing Antiquated Voting Equipment

The lifespan of electronic voting machines can vary, but experts agree that systems over a decade old are more likely to need to be replaced for security and reliability reasons.[4] We estimate that in November 2018, 34 percent of all local election jurisdictions were using voting machines that were at least 10 years old as their primary polling place equipment (or as their primary tabulation equipment in all vote-by-mail jurisdictions).[5] This number includes counties and towns in 41 states.[6]

States, however, have made significant progress in replacing such machines since 2016. In 2017, Michigan began replacing its aging voting equipment statewide while Virginia decertified and replaced all paperless voting machines.[7] In 2018, Arkansas completed the replacement of its remaining antiquated paperless voting equipment.[8] In several other states, such as Colorado, Florida, and Nevada, significant replacement has happened at the local level since 2016.

These efforts are ongoing and expanding across the country in 2019, and several states are in route to having new voting machines in time for the 2020 elections. For instance, Ohio approved $114.5 million to replace aging voting machines ahead of the 2020 presidential election; California issued a requirement for counties to replace old voting machines by March of 2020; and North Dakota recently spent $11 million on new voting machines, which the secretary of state expects to be in place by the end of the year.[9]

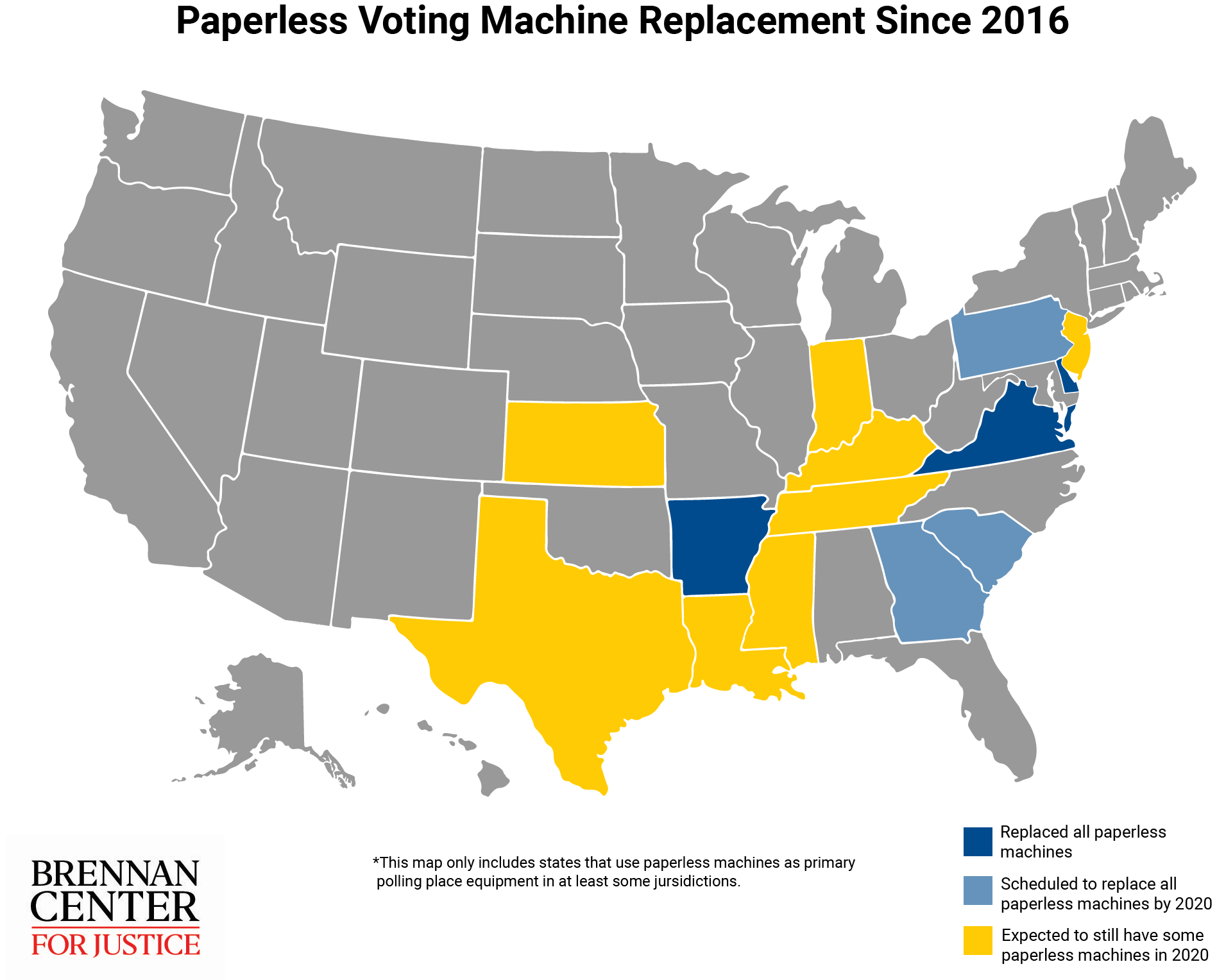

Nearly Half of the States with Paperless Voting Machines in 2016 Will Have Replaced These Machines by the 2020 Elections

Action is also being taken to replace electronic voting machines that don’t produce a voter verifiable paper record in many of the states that still use them. Experts have long warned that these machines are a security risk because they do not allow election officials or the public to confirm electronic vote totals.[10] The Brennan Center estimates that compared to 2016, when approximately 27.5 million voters cast their ballots on paperless machines, a little over half, or as many as 16 million, will do so in 2020—though that number could go even lower with additional funding from Congress.[11] As the Brennan Center has previously found, many election officials would like to replace their equipment before 2020 but do not currently have the funds to do so.[12] A recent survey of election officials by Politico produced similar findings, noting that “many election officials have been slow to buy paper-based machines,” in part due “to a lack of money”.[13]

In 2016, 14 states used paperless voting machines as the primary polling place equipment in at least some of their counties and towns (Arkansas, Delaware, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, Mississippi, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, Tennessee, and Virginia).[14]

Today, just 11 states use paperless machines as their primary polling place equipment in at least some counties and towns, as Virginia, Arkansas, and Delaware transitioned to paper-based voting equipment in 2017, 2018, and 2019, respectively.[15] In addition to these states, three more (Georgia, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania) have committed to replacing equipment by 2020. Consequently, we expect the number of states using paperless equipment as primary systems in at least some counties and towns will drop to no more than eight.[16]

Even so, a significant number of voters may not have a paper record of their vote in 2020. Using voter registration and turnout data from the 2016 and 2018 Election Administration and Voting Survey and 2018 voting equipment data from Verified Voting, we estimate that as many as 12 percent of voters (approximately 16 million voters) will vote on paperless equipment in November 2020. This compares to 20 percent of voters (27.5 million) in 2016.[17]

In its July report, the Senate intelligence committee noted that “paper ballots and optical scanners are the least vulnerable to cyber-attack.”[18] The vast majority of jurisdictions with voter verifiable paper records use such systems. But a minority of jurisdictions in 2020 will use Direct-Recording Electronic (DRE) machines with voter verifiable paper trails (VVPTs) or Ballot-Marking Devices (BMDs) as their primary polling place voting equipment. Approximately 6 percent of registered voters live in jurisdictions where the primary polling place equipment will be DREs with VVPTs and around 7.5 percent live in jurisdictions where the primary polling place equipment will be BMDs.[19]

These devices collect the voter’s choices and either produce a ballot that is then scanned by the voter in a separate scanner (BMDs) or create a “paper trail” that is preserved for potential review later. Experts have warned that some of these paper trails or ballots can be difficult to review.[20] Before purchasing such systems, election officials should consider how easy it will be for voters to review and understand the machine marked ballots. In jurisdictions where either system is used, election officials should put in place procedures that make it more likely voters will review and catch errors on the paper record, as well as consider additional security measures recommended by experts.[21]

II. Progress on Post-Election Audits

Paper-based systems provide better security because they create a paper record that voters can review before casting their ballot. Election officials can review these records during an audit after the election. However, these paper records will be of little security value unless they are used to check and confirm electronic tallies.

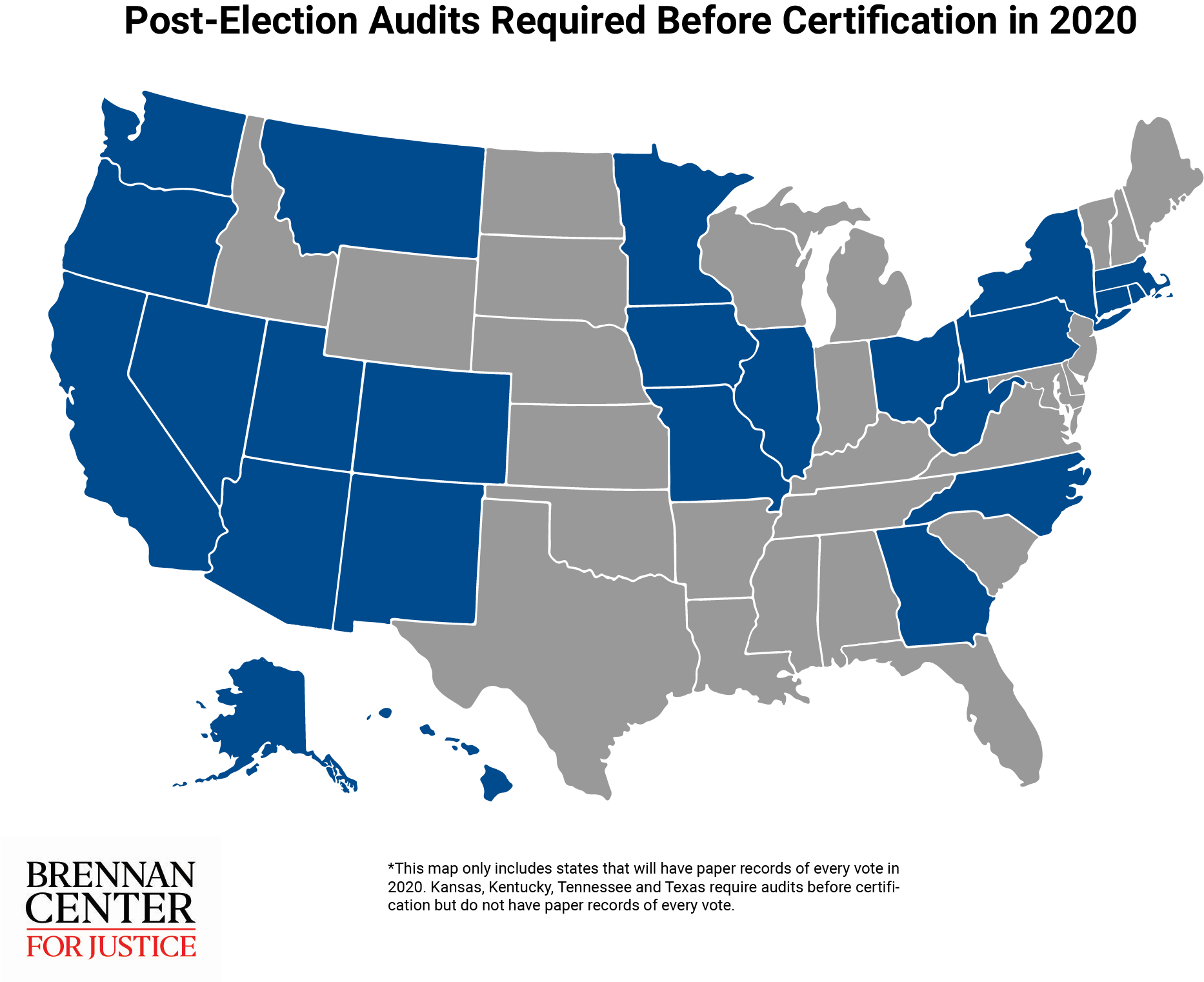

Traditional post-election audits, which generally require manual inspection of paper ballots cast in randomly selected precincts or on randomly selected voting machines, can provide assurance that individual voting machines accurately tabulated votes. Multiple states have employed these audits for over a decade. Currently, 22 states and the District of Columbia have voter verifiable paper records for all votes cast and require post-election audits of those paper records before certifying election results.[22]

This number should go up to at least 24 states by the November 2020 elections, after Pennsylvania and Georgia fully transition to paper-based equipment.[23] In total, these 24 states and the District of Columbia make up 295 electoral votes. The remaining 26 states, totaling 243 electoral votes, do not currently require post-election audits of all votes prior to certification. However, there is nothing stopping most of these remaining states from conducting such audits if they have the resources and will to do so.

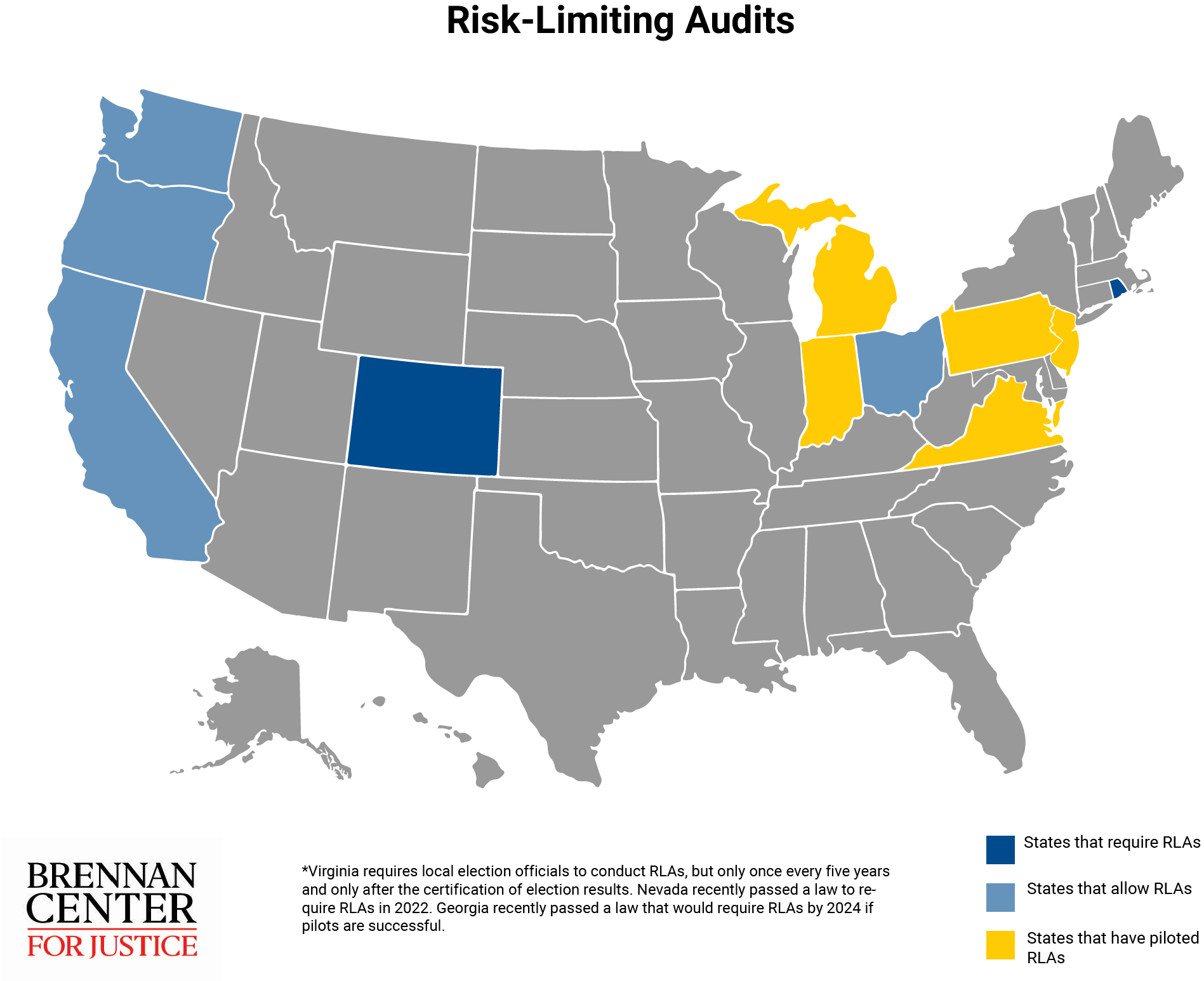

A New “Gold Standard”: Risk-Limiting Audits

Risk-limiting audits are a comparatively new procedure and offer two important improvements to traditional audits. They are generally more efficient, requiring a review of a smaller number of ballots during the audit process. And the statistical modeling used is designed to detect potential inaccuracies in election outcomes, whether they are the result of accidental or intentional interference. RLAs can provide assurance that the reported winner did, in fact, win the election, instead of a traditional audit, which only assures officials that machines are working correctly. [24] Because of these features, the Brennan Center and many other experts have urged broad adoption of RLAs.

States have embraced RLAs at a rapid rate: Colorado was the first state to implement RLAs in 2017.[25] Not even two years later, more than 12 states are experimenting with the procedure in some fashion.

Currently, Colorado and Rhode Island require RLAs immediately after an election before results are legally certified; Nevada will do the same starting in 2022, thanks to recently passed legislation.[26] (Local election officials in Virginia are also required to use the procedure, but only once every five years and only after certification.)[27] Washington and Ohio allow election officials to select RLAs from a set of post-election audit options; California enacted a similar law last year that will apply for most of 2020.[28]

Election officials in a slew of these and other states — such as Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia — have either already launched RLA pilots or plan to do so moving forward.[29] Michigan plans to conduct its first state-wide RLA pilot during the March 10 presidential primary, marking the first time that RLAs will be used in conjunction with the presidential election process in Michigan.[30]

Meanwhile, state legislatures continue to explore the proposal: a bill authorizing RLAs recently passed the Oregon state legislature, and lawmakers are considering RLA-related legislation in New Jersey, Ohio, and South Carolina.[31] Although some states were able to use the $380 million from 2018 to pilot RLAs, many states had other urgent needs, such as replacing aging voting machines and registration databases, and have not yet been able to.[32]

Conclusion

While there has been substantial progress in securing voting machines since 2016, there is still more to do ahead of 2020. As both the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and National Academy of Sciences have noted, we should replace antiquated equipment, and paperless equipment in particular, as soon as possible.[33] Moreover, of the 42 states that should have paper records of every vote by 2020, 17 are not currently required to conduct post-election audits pre-certification.[34] And as the Brennan Center and other organizations have noted in Defending Elections, election security goes far beyond securing voting machines. In addition to the items discussed in this analysis, states and counties need more resources for items like cybersecurity support for local election jurisdictions, and upgrades to voter registration databases and other critical election systems.[35]

With research and writing support from William Dobbs-Allsopp.

Credit:Getty/Shutterstock/BCJ