The Equal Rights Amendment, Explained

Thirty-eight states have finally ratified the ERA, but whether its protections for women’s rights are actually added to the Constitution remains an open question.

Part of

On January 15, 2020, Virginia became the latest state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), a proposed amendment to the Constitution that guarantees equal rights for women. The measure emerged as a top legislative priority after Democrats took control of both houses of the Virginia General Assembly for the first time in two decades, leading to the election of the first female speaker of the state’s House of Delegates. It received bipartisan support in both chambers. This historic vote follows recent ratifications by Nevada in 2017 and Illinois in 2018 after four decades of inactivity.

The Constitution provides that amendments take effect when three-quarters of the states ratify them, putting the current threshold at 38 states. Virginia was the 38th state to ratify the ERA since Congress proposed it in 1972, technically pushing the ERA across that threshold. And yet, there are still hurdles in the ERA’s path. The ratification deadlines that Congress set after it approved the amendment have lapsed, and five states have acted to rescind their prior approval. These raise important questions, and now it is up to Congress, the courts, and the American people to resolve them.

What is the Equal Rights Amendment?

The Equal Rights Amendment was first drafted in 1923 by two leaders of the women’s suffrage movement, Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman. For women’s rights advocates, the ERA was the next logical step following the successful campaign to win access to the ballot through the adoption of the 19th Amendment. They believed that enshrining the principle of gender equality in our founding charter would help overcome many of the obstacles that kept women as second-class citizens.

While the text of the amendment has changed over the years, the gist of it has remained the same. The version approved by Congress in 1972 and sent to the states reads:

“Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex. The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.”

Beginning in 1923, lawmakers introduced the ERA in every session of Congress, but it made little progress until the 1970s. It didn’t help that for most of the twentieth century, Congress was comprised almost entirely of men. In the nearly five-decade span between 1922 and 1970, only 10 women served in the Senate, with no more than 2 serving at the same time. The picture was only slightly better in the House.

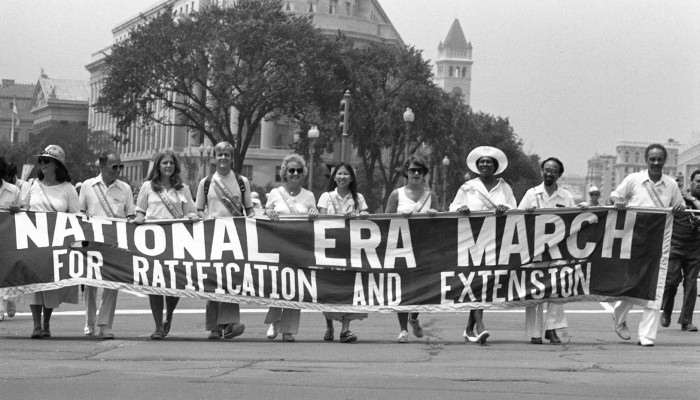

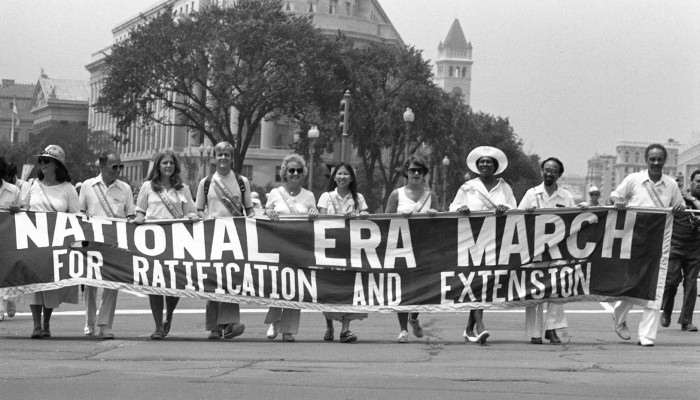

In 1970, a new class of women lawmakers — including Reps. Martha Griffiths (D-MO) and Shirley Chisholm (D-NY) — pressed to make the ERA a top legislative priority. They had to overcome the resistance of Rep. Emanuel Celler (D-NY), the powerful chairman of the House Judiciary Committee who had refused to hold a hearing on the ERA for over 30 years. Faced with increased pressure, Celler finally relented. In March 1972, the amendment passed both chambers of Congress with bipartisan support far exceeding the two-thirds majorities required by the Constitution. Congress promptly sent the proposed amendment to the states for ratification with a seven-year deadline.

Why wasn’t the ERA ratified by its original deadline?

Within a year, 30 of the necessary 38 states acted to ratify the ERA. But then momentum slowed as conservative activists allied with the emerging religious right launched a campaign to stop the amendment in its tracks. Phyllis Schlafly, a conservative lawyer and activist from Illinois who led the STOP ERA campaign, argued that the measure would lead to gender-neutral bathrooms, same-sex marriage, and women in military combat, among other things.

The opposition campaign was remarkably successful. Support for the ERA eroded, particularly among Republicans. Though the GOP was the first party to endorse the ERA back in 1940, GOP lawmakers cooled to the amendment, leading to a stalemate in the states.

By 1977, only 35 states had ratified the ERA. Though Congress voted to extend the ratification deadline by an additional three years, no new states signed on. Complicating matters further, lawmakers in five states — Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, Kentucky, and South Dakota — voted to rescind their earlier support.

In 1982, following the expiration of the extended deadline, most activists and lawmakers accepted the ERA’s defeat. But in the four decades since Congress first proposed the ERA, courts and legislatures have realized much of what the amendment was designed to accomplish. A significant portion of the credit goes to Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who as the founding director of the ACLU Women’s Rights Project found success in arguing for a jurisprudence of gender equality under the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

And yet, despite these dramatic and important gains for women’s rights, pervasive gender discrimination persists in the form of wage disparities, sexual harassment and violence, and unequal representation in the institutions of American democracy.

Why is there revived interest in the ERA today?

In recent years there has been a resurgence of women’s activism, from the Women’s March on Washington to the #MeToo Movement to the record number of women elected to Congress and state legislatures in 2018. Amid this renewed focus on issues of gender equality, lawmakers and advocacy organizations like the ERA Coalition have put the amendment back on the nation’s agenda.

The renewed push to adopt the ERA captured public attention in 2017, when Nevada became the first state to ratify the measure since 1977. A key ERA champion, State Sen. Pat Spearman, explained, “This is the right thing to do, it’s the right time to do it, and so we just ought to do it.”

In 2018, the Illinois legislature followed suit. “This is our generation’s chance to correct a long standing wrong,” argued Illinois State Rep. Steven Andersson, a Republican who helped shepherd the measure. With each new ratification, there has been increased GOP support for the ERA.

Proponents argue that adoption of the ERA can advance the cause of equality in the twenty-first century, but key questions remain. Julie Suk, a sociologist and legal scholar at the CUNY Graduate Center, has asked, “If ratified in the coming year, how should we construe the meaning of a constitutional amendment introduced almost a century ago and adopted half a century before full ratification?”

Over the last year, Brennan Center experts were among those to weigh in on the debate.

Jennifer Weiss-Wolf, the Brennan Center’s Women and Democracy Fellow, noted that the ERA would empower Congress “to enforce gender equity through legislation and, more generally, the creation of a social framework to formally acknowledge systemic biases that permeate and often limit women’s daily experiences.” And it would create consistency to address the patchwork ways gender and economic inequity are often addressed in our current laws. Among the “lingering legal and policy inequities the ERA would help rectify,” she identified the emerging issue of menstrual equity as a legal and policy issue “the ERA could further refine and bolster.”

Brennan Center Fellow Wilfred Codrington (also co-author of this piece) considered whether the ERA, framed as “an explicit, permanent constitutional provision outlawing gender discrimination,” is sufficient to meet the challenge of inequality today. “Lawmakers are justified in adopting the ERA,” Codrington argued, “even if it’s uncertain that the amendment would fully achieve its advocates’ desired ends.” But courts should also draw on their constitutional authority based in equity — defined as “recourse to principle of justice to correct or supplement the law” — which can reinforce their legal equality analysis and equip them to address “a broader spectrum of anti-discrimination cases … with greater nuance.”

John Kowal, the Brennan Center’s Vice President for Programs, explored the legal and procedural questions for Congress, the courts, and the American people arising out of the ERA’s surprising revival after a long period of dormancy. Should the push to ratify the 1972 version of the ERA fail on procedural grounds, Kowal also considered the advantages of starting the amendment process anew given the amendment’s strong base of public support. “When a powerful social movement with deep popular support takes up the goal of constitutional change,” he said, “history shows that this is a battle that can be won.”

What are the key legal challenges today?

Does Virginia’s vote to ratify the ERA mean it will be adopted as the 28th Amendment to the Constitution? The answer hinges on two procedural questions with no settled answer.

First, can Congress act now, nearly 48 years after first proposing the ERA, to waive the lapsed deadline? ERA supporters have long argued that just as Congress had the power to set a deadline, they have the power to lift one. Senate Joint Resolution 6, a bipartisan measure sponsored by Sens. Ben Cardin (D-MD) and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) which is currently pending in Congress, seeks to do just that. But while the ERA’s deadline was extended prior to the deadline, there is no precedent for waiving the deadline after its expiration.

Second, can states act to rescind their support of a constitutional amendment before it is finally ratified? Congress confronted this question twice, during the ratification of 14th and 15th Amendments in the years immediately following the Civil War. In each instance, Congress adopted resolutions declaring the amendments ratified, ignoring the purported state rescissions. But in 1980, a federal district court in Idaho ruled that the state’s rescission of the ERA was valid.

Who will decide these questions? Under a 1984 law, the Archivist of the United States is charged with issuing a formal certification after three-quarters of the states have ratified an amendment. When there has been doubt over the validity of an amendment, Congress has acted to declare it valid. This occurred most recently in 1992 when the states ratified the 27th Amendment, 203 years after Congress proposed it.

On January 8, the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) issued an opinion arguing that the deadline set by Congress is binding and that the ERA “is no longer pending before the States.” Notably, the opinion rejects the conclusion of the 1977 OLC opinion, which approved of the earlier extension of the ERA’s ratification deadline. In response, the National Archives and Records Administration has said that the archivist of the United States, Daniel Ferriero, will not certify Virginia’s ratification or add the ERA to the Constitution until a federal court issues an order. (Ferriero had previously accepted the ratifications from both Nevada and Illinois.)

But would the courts have a say in this controversy? In a 1939 case, the Supreme Court ruled that the question of whether an amendment has been ratified in a reasonable period of time is a “political question” best left in the hands of Congress, not the courts. If Congress acts to waive the deadline, would the courts continue to honor that precedent? How much weight would they give to the view of the American people, who strongly support the ERA according to recent polls?

In sum, Virginia’s vote to ratify the ERA has spurred an important legal and policy debate. However the disputes over the amendment’s validity are resolved, it is clear is that the conversation around the ERA, an amendment that is already nearly a century in the making, is not likely to end in 2020.