Florence Ellinwood Allen: The First Woman State Supreme Court Justice

A century later, her story of perseverance and support from women’s rights activists still inspires.

One hundred years ago, Florence Ellinwood Allen became the first woman to serve as a state supreme court justice. It was one of many firsts throughout her life: she was also the first woman in America to serve as a prosecutor, be elected as a trial court judge, and be appointed to a federal appeals court. Allen overcame numerous barriers based on her gender throughout her legal career, often with the support of grassroots suffragists who rallied behind her. Her achievement is underscored by the fact that there wasn’t another woman on a state supreme court for nearly 40 years.

Allen spent her first year of law school at the University of Chicago, where she was the only woman. She later wrote in her memoir that it was “terrifying to have to enter a classroom first while a hundred men stood aside.” Allen transferred to New York University, which had been accepting women to its law school since 1890. There, she described feeling “on equal terms with men” and became involved in the women’s suffrage movement.

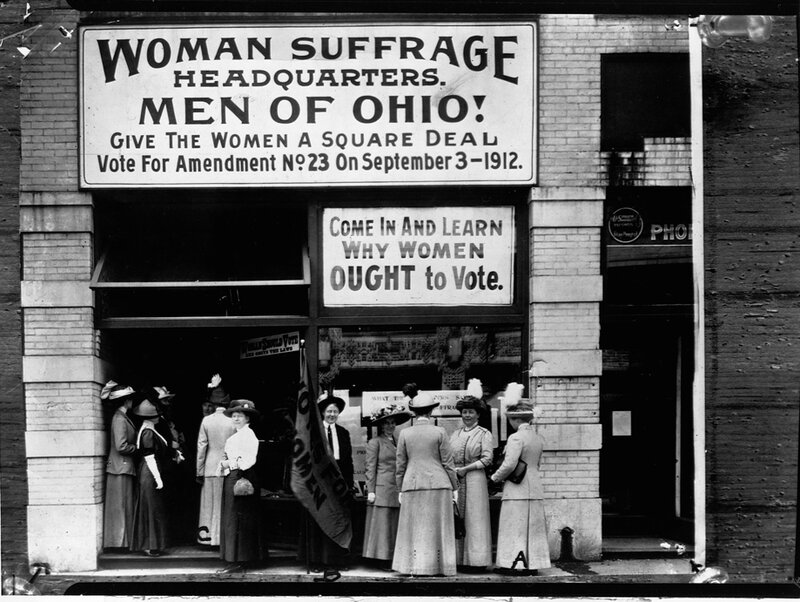

Allen graduated law school second in her class in 1913 and returned home to Ohio, where she opened a private law practice, volunteered for the Legal Aid Society, and continued campaigning for suffrage. While advocating for a ballot initiative to grant Ohio women the right to vote, Allen gave speeches in 88 counties across the state. She later argued and won a case before the state supreme court that granted women the right to vote in municipal elections, although the policy was soon overturned by referendum. In 1919, Allen was appointed as a prosecutor in Cuyahoga County, a national first for a woman.

Just 10 weeks after the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, Allen was elected to the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas and became the first woman elected to judicial office in the country. Because she entered the race late, she had to collect signatures to be listed on the ballot. Her friends in the Woman Suffrage Party circulated petitions throughout the county and collected enough signatures to complete the nomination process. Upon Allen’s election, her male colleagues on the court suggested that she should only rule on marital disputes. Allen disagreed, responding that since she had never married, “she lacked sufficient expertise in the domestic domain,” unlike the men on the bench.

The women’s movement remained deeply involved throughout Florence’s tenure on the court. When Allen called attention to disorganization at the court due to the lack of a chief justice, women’s groups contacted the press and organized mass meetings to raise awareness of the problem. Allen later wrote that this burst of civic engagement among women occurred “because for the first time they were serving on the jury and also because they saw a member of their sex sitting on the bench . . . in a way that made them feel a special ownership in the Court of Common Pleas.”

In 1922, Allen ran for a seat on the Ohio Supreme Court. She was the underdog against a decorated World War I veteran backed by the powerful state Republican party. However, Allen prevailed by a significant margin. Her campaign was driven by “Florence Allen clubs,” which had been organized by suffragists in almost every single Ohio county. Allen relied on this network of volunteers to circulate petitions, organize door-to-door canvassing, schedule speaking engagements, and secure endorsements from local newspapers.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Allen wrote in her memoir that on her first day on the bench, she “was aware of a certain uneasiness among the men” due to her gender. Allen overcame their uncertainty and asserted her judicial authority during her 11 years on Ohio’s highest court, issuing decisions on questions of education, labor, municipal governance, taxes, and more.

In 1928, the Florence Allen clubs returned in force, and Allen was reelected by a margin of some 350,000 votes.

After unsuccessful campaigns for the U.S. Senate and House, Allen was nominated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in 1934. She faced considerable opposition throughout the confirmation process but found support from unlikely allies. Ohio Supreme Court Justice Will Stephenson, who had staunchly opposed the idea of a woman justice when Allen was first nominated to share the bench with him, traveled to Washington to testify that “there is no Court too big for Judge Allen.” Allen was confirmed by the Senate, becoming the first woman to sit on a federal appeals court bench. She remained in this position for 25 years.

On the Sixth Circuit, Allen maintained that her role as a judge should not be impacted by her gender. Upon noticing that the chief judge was not assigning her to hear any cases involving patents, Allen insisted that she no longer be excluded from this category. She later wrote several opinions on patent-related cases that were affirmed by the Supreme Court.

Allen received national attention when she presided over a three-judge panel in the case of Tennessee Electric Power Co. v. Tennessee Valley Authority, ruling that the federal government had the authority to build dams and reservoirs and regulate interstate commerce on interstate waterways like the Tennessee River.

This case raised Allen’s national profile, and she was considered for the Supreme Court by several presidents. Many allies called for Allen to be nominated, including First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who wrote in her newspaper column in 1948, “if a President of the United States should decide to nominate a woman for the Supreme Court, it should be Judge Allen.”

Florence Ellinwood Allen was a trailblazer who understood the importance of diversity in the courtroom. In her words, “When women of intelligence recognize their share in and their responsibility for the courts, a powerful moral backing is secured for the administration of justice.”

A century after her election to the Ohio Supreme Court, Allen’s story reminds us of the importance of a representative judiciary to affirm the legitimacy of a system that administers justice for all. There is still much work to be done on that front: as of last year, only about one-third of active lower federal court judges were women, and 12 states had only one woman on the bench of their state supreme court.