In 2016 as a member of Congress, Deb Haaland stood for four days in solidarity with protesters at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation against construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Today, as the first Native American to be the secretary of the interior — the first to lead any cabinet department — she has the opportunity to support the First Amendment rights of the protesters she joined in the past.

With her authority over energy development on federal lands, Haaland can be a voice for Indigenous and climate movements facing an urgent threat: the rapid spread of laws to protect “critical infrastructure” that single out activists.

Since 2016, 13 states have quietly enacted laws that increase criminal penalties for trespassing, damage, and interference with infrastructure sites such as oil refineries and pipelines. At least five more states have already introduced similar legislation this year. These laws draw from national security legislation enacted after 9/11 to protect physical infrastructure considered so “vital” that the “incapacity or destruction of such systems and assets would have a debilitating impact on security, national economic security, national public health or safety.”

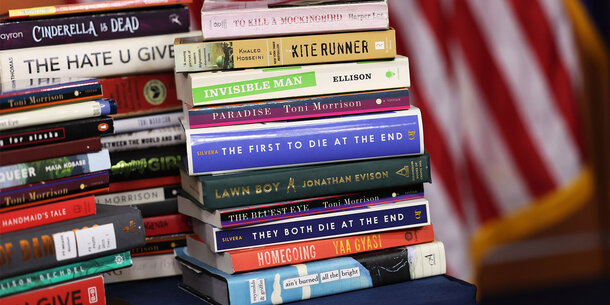

Many industry sectors are designated critical infrastructure, including food and agriculture, energy, water and wastewater, and communications, but most state critical infrastructure laws focus more narrowly on oil and gas pipelines. While protecting critical infrastructure is a legitimate government function, these laws clearly target environmental and Indigenous activists by significantly raising the penalties for participating in or even tangentially supporting pipeline trespassing and property damage, crimes that are already illegal. Many laws are modelled on draft legislation prepared by the American Legislative Exchange Council, also known as ALEC, a powerful lobbying group funded by fossil fuel companies like ExxonMobil and Shell.

Central to the new critical infrastructure laws are increased criminal penalties and vague, broad definitions that could discourage protest and particularly, nonviolent civil disobedience. Many laws make any “damage” to or “interference” with a facility deemed critical infrastructure a felony. Under Ohio’s law, trespass with the purpose of “tampering” with a facility is a third degree felony punishable by up to 10 years in prison and a $20,000 fine. In Indiana, a felony conviction is applied for any facility trespass, a crime that is typically a misdemeanor or fine.

Vague language like “damage,” “tamper,” and “impede” in critical infrastructure laws makes it unclear if, for example, knocking down safety cones and starting a fire next to a natural gas facility are the same under the law. Many critical infrastructure laws do not clarify if they apply only to land a company fully owns or also to pipeline easements, which run through both public and private lands. At least some laws apply to both. Only a week after Louisiana’s critical infrastructure law was enacted, opponents of the Bayou Bridge pipeline were charged with trespassing for boating on public waters on the border of a pipeline easement.

The combination of overly broad language and steep penalties in critical infrastructure laws make it likely that future activists and supporting organizations will be discouraged from exercising their First Amendment-protected protest rights. A lawsuit brought in response to the Bayou Bridge charges will test the laws for the first time on First Amendment grounds.

Many of these laws even extend beyond the protesters. In a proposed law in Minnesota, anyone who “recruits, trains, aids, advises, hires, counsels, or conspires” someone to trespass without a “reasonable effort” to prevent the trespassing is guilty of a gross misdemeanor. In Oklahoma, organizations that conspire with perpetrators are liable to be fined up to $1 million. These laws may infringe on the freedom of association protected under the First Amendment. Indeed, the Supreme Court ruled that the illegal actions of a few individuals do not implicate an entire group.

The criminalization of environmental protest is fueled by federal security agencies and oil and gas companies, who are often major political donors. For years, the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Bureau of Investigation have labelled activists at infrastructure sites as domestic terrorists and violent extremists in order to justify further surveillance and policing. Government documents have been released that detail the FBI’s focus on “Animal Rights/Environmental Extremism,” describing even nonviolent protesters as extremists.

At Standing Rock, a private security firm hired by the pipeline companies consistently referred to protesters as “terrorists” while working with law enforcement. Ahead of the Keystone XL pipeline protests in 2018, DHS agents held an “anti-terrorism training” for state and local authorities. In contrast, members of the far-right militant group the Three Percenters have established a significant presence at oil and gas plants with little law enforcement reaction.

To be sure, as the recent power outages in Texas showed so vividly, the United States needs reliable energy. But it’s questionable whether pipeline construction sites that could feasibly be moved or replaced with renewable energy sources should legitimately be considered “vital” to the energy grid. Furthermore, a singular focus on this aspect of security comes at the cost of others. Whose essential resources do pipeline projects protect and whose do they threaten? Black Americans are disproportionately likely to live near natural gas pipelines and experience higher cancer risk due to unclean air. An oil spill from the Dakota Access Pipeline could devastate the Sioux Tribe’s water source. Meanwhile, on some reservations, 10 percent of households lack electricity and as many as 40 percent of households must haul water and use outhouses. The well-being of these communities must count too.

The rise in critical infrastructure laws may foreshadow more anti-protest legislation to come. A similar wave of anti-protest laws has already begun in response to the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. State legislators contemplating critical infrastructure laws should bear in mind that laws that criminalize trespassing and protect the safety of construction workers and law enforcement already exist. Critical infrastructure laws don’t fill an unmet need — they only raise the penalties for specific groups of people. Courts adjudicating First Amendment challenges in the coming years should recognize that these laws are overbroad and impose disproportionately severe penalties that chill freedom of assembly and association.

As secretary of the interior, Haaland promises to uplift the voices of Indigenous and climate protesters in the Biden administration. State legislators, law enforcement, and the fossil fuel industry should follow suit and listen to these activists rather than suppressing constitutionally protected activity under the guise of national security.