In the wake of the 2020 election, the machinery of disinformation began spreading the Big Lie that a massive and coordinated electoral fraud campaign led to President Trump’s defeat. Some of this disinformation came from his legal team as well as the president himself, and these false claims were amplified and spread by far-right broadcasts on networks such as One America News Network (OAN) and Fox News. While politician Sarah Palin recently failed in a defamation suit against the New York Times, a company called Dominion Voting Systems Inc. may well succeed in its defamation suit against these two news organizations.

Each news organization trained its sights on Dominion Voting Systems Inc., a manufacturer of voting machines used in 28 states. The accusations were so vile and repetitive that Dominion filed defamation suits against Fox, OAN, and attorney Sidney Powell, a member of Trump’s legal team, among others. In the suit against Fox, Dominion stated that “[i]f this case does not rise to the level of defamation by a broadcaster, then nothing does." In its filing on OAN, the complaint argued, “OAN helped create and cultivate an alternate reality where up is down, pigs have wings, and Dominion engaged in a colossal fraud to steal the presidency from Donald Trump by rigging the vote.”

After the 2020 election, Powell alleged that Dominion’s voting machines were unreliable, hacked, or flipped votes. When she tried to get the Dominion’s defamation case dismissed, the district court ruled against her, stating, “Powell contends that no reasonable person could conclude that her statements were statements of fact because they ‘concern the 2020 presidential election, which was both bitter and controversial.’ . . . It is true that courts recognize the value in some level of ‘imaginative expression’ or ‘rhetorical hyperbole’ in our public debate. But it is simply not the law that provably false statements cannot be actionable if made in the context of an election.”

These suits test the reach of the First Amendment and the extent to which lies are considered protected speech. The Supreme Court has determined that published lies or inaccuracies are entitled to at least some First Amendment protection in many instances as the price of facilitating political debate and deliberation in our democracy. The Court also decided, however, that when “actual malice” is present, that protective coverage no longer extends. Is the Big Lie protected by the First Amendment? Or do the actions of the press and the president’s lawyers meet the actual malice standard?

The outcome of these suits may signal whether the Supreme Court is ready to overturn precedent and put tighter reins on speech or if it will offer a new set of guidelines to determine when election lies are unconstitutional and punishable by law.

The actual malice standard

Because some of Dominion’s defamation suits are against the press, they raise the issue of whether the actual malice standard from the landmark 1964 case of New York Times v. Sullivan should remain in place.

Sullivan was a case where a public safety commissioner in Alabama, L.B. Sullivan, took offense to an ad in the New York Times that was raising money for Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders. The ad contained some factual errors that Sullivan claimed defamed him. He sued and won a $500,000 judgment against the New York Times in lower courts. The Supreme Court reversed the decision, calling it “constitutionally deficient for failure to provide the safeguards for freedom of speech and of the press that are required by the First and Fourteenth Amendments in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct.”

This case created the actual malice standard, which states, “[t]he constitutional guarantees require . . . a federal rule that prohibits a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves that the statement was made with ‘actual malice’—that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” This was a departure from the common law tradition, which had previously provided defamed individuals a greater ability to sue the press and win.

The rationale for the Court’s decision in support of broader protection for freedom of the press — including the freedom to publish errors and inaccuracies — was that it “consider[ed] this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.” Sullivan provides protection so that the press need not censor its critiques of elected and appointed government officials.

Though Sullivan ensured that the press could criticize those in political power, the Supreme Court expanded the actual malice standard to public figures as well. While determining who qualifies as a public official is reasonably straightforward, “public figure” is inherently subjective and depends on how well-known a particular plaintiff is.

The Supreme Court did make clear that private individuals (non-public figures and non-government officials) were not covered by the actual malice standard in part because it was so much harder for a private, non-famous individual to get their good name back after it was defamed. As the Supreme Court noted in Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., “private individuals are not only more vulnerable to injury than public officials and public figures; they are also more deserving of recovery.” Thus, the Court left the rules for defamation of private individuals up to the 50 states. And it made clear that someone experiencing 15 minutes of fame did not mean that they were a public figure. As the Supreme Court explains in Wolston v. Reader’s Digest, “[a] private individual is not automatically transformed into a public figure just by becoming involved in or associated with a matter that attracts public attention.”

There were criticisms of the actual malice standard from the beginning. In their concurrence in Sullivan, Justices Hugo Black and William Douglas warned that “malice” was “an elusive, abstract concept, hard to prove and hard to disprove. The requirement that malice be proved provides at best an evanescent protection for the right to critically discuss public affairs and certainly does not measure up to the sturdy safeguard embodied in the First Amendment.”

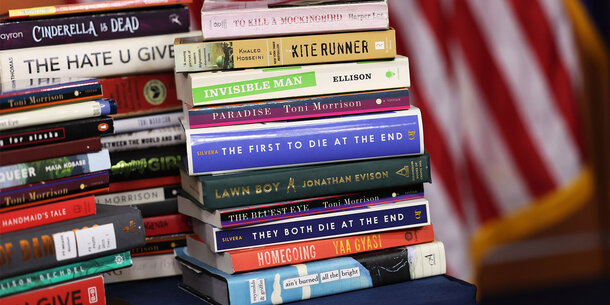

In the past few years, Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch have raised questions about whether Sullivan’s actual malice standard should persist in cases where public figures have their reputations tarnished by lies in the press. Thomas raised some eyebrows when he wrote a concurring opinion from a denial of certiorari in McKee v. Cosby, a case in which a woman who accused entertainer Bill Cosby of sexual assault was deemed to be a limited public figure and consequently lost her defamation case because she could not satisfy the high actual malice standard. He went on to argue that “New York Times [v. Sullivan] and the Court’s decisions extending it were policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law.”

In 2021, Gorsuch joined Thomas’ criticism in Berisha v. Lawson, in which the Supreme Court declined to hear a case where the plaintiff sued an author for defamation based on his characterization in the author’s book. Gorsuch wonders aloud, “[a]s Sullivan’s actual malice standard has come to apply in our new world, it’s hard not to ask whether it now even ‘cut[s] against the very values underlying the decision.’”

Dominion’s libel suits

Dominion is suing OAN and Fox News in separate suits for repeatedly airing claims like the ones articulated above by Ms. Powell. Dominion’s suit against OAN is particularly stark in its allegations:

To capitalize on the interest its target audience had in the false Dominion narrative, OAN effectively deputized its Chief White House Correspondent, Chanel Rion, as an in-house spokesperson for all Dominion-related content. After priming its viewers with a steady diet of post-election programming falsely claiming Dominion rigged the 2020 election, OAN and Rion began producing an entire line of programming exclusively devoted to defaming Dominion, descriptively named ‘Dominion-izing the Vote,’ which branded OAN’s disinformation and defamation campaign against Dominion into a single catchy phrase that is now synonymous with fraudulently flipping votes.

The complaint also alleges that “in February 2021, months after the 2020 election, OAN enlisted MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell to broadcast a series of multi-hour-long ‘documentaries’ spreading disinformation about Dominion. Lindell falsely claimed that Dominion was behind ‘the biggest cyber-attack in history,’ and that Lindell had ‘absolute proof.’” Thus, OAN was tainting Dominion’s brand through its constant leveling of conspiracy theories against the company.

Dominion argued in its suit that OAN met the high burden of showing actual malice, stating that OAN’s “defamatory statements were accompanied with malice, wantonness, and a conscious desire to cause injury.” OAN’s efforts to dismiss this suit are still pending.

While Fox’s actions were slightly less egregious than OAN’s behavior, Fox’s considerably larger audience conceivably did more damage to Dominion’s reputation. As Dominion alleged in its complaint for defamation, “[t]hese lies transformed Dominion into a household name. As a result of Fox’s orchestrated defamatory campaign, Dominion’s employees, from its software engineers to its founder and chief executive officer, have been repeatedly harassed. Some have even received death threats. And of course, Dominion’s business has suffered enormous and irreparable economic harm.”

Dominion tried to get Fox to correct its erroneous statements in real time by sending written rebuttals to false claims made by the network and its on-air personalities. As Dominion alleged in its complaint: “even after Fox was put on specific written notice of the facts, it stuck to the inherently improbable and demonstrably false preconceived narrative and continued broadcasting the lies of facially unreliable sources—which were embraced by Fox’s own on-air personalities—because the lies were good for Fox’s business.” While Fox corrected the record with regards to Smartmatic, a different voting machine company, Fox did not relent on the matter of Dominion voting machines.

When the issue reached the courts, a Delaware state judge in the Dominion v. Fox case rejected all of Fox’s First Amendment arguments and denied Fox’s motion to dismiss the case. Fox attempted to argue that, as press, it was immunized from liability for defamation if what they were reporting was “newsworthy.” But this did not convince the judge, who concluded, “[t]he United States Supreme Court has attempted to strike a balance between First Amendment freedoms and viable claims for defamation [and] declined to endorse per se protected categories like newsworthiness.”

The court noted “[t]he Complaint supports the reasonable inference that Fox either (i) knew its statements about Dominion’s role in election fraud were false or (ii) had a high degree of awareness that the statements were false.” Moreover, the court found “that the Complaint alleges facts that Fox made the challenged statements with knowledge of their falsity or with reckless disregard of their truth.” The court concluded that it could “infer that Fox intended to avoid the truth.”

How Dominion’s lawsuits may change First Amendment law

Dominion’s billion dollar suits against Fox and OAN raise a host of thorny questions: Should suits against the press for defamation be easier to win? Should statements about public figures and public officials be held to the same standard as statements about private citizens? Should a corporation like Dominion be deemed a “public figure” for libel purposes?

These questions seem destined to reach the Supreme Court in one form or another, as demonstrated in the recently dismissed libel suit brought by former Alaska governor and vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin against the New York Times.

On the one hand, the ability of the free press to report on ongoing events will involve innocent errors. On the other, defamatory misstatements about persons or companies can do far more financial and reputational damage today than they could in 1964 given the reach of cable news and internet audiences. The series of outrageous claims about Dominion’s voting machines could well make new case law and provide the Supreme Court a chance to articulate which types of lies about elections are actionable.

Dominion’s suits point to the direct harm to democracy that disinformation can cause. As NPR reported, “Dominion’s court filing alleges that Fox ‘recklessly disregarded the truth’ – and that some of its viewers believed the channel’s narrative with such fervor that they ‘took the fight from social media to the United States Capitol and at rallies across the country to #StopTheSteal, inflicting violence, terror, and death along the way.’” And moreover, “‘[t]he lies did not simply harm Dominion,’ the company’s lawsuit says. ‘They harmed democracy. They harmed the idea of credible elections. They harmed a once-unshakeable faith in democratic and peaceful transfers of power.’” In other words, the small-d democratic stakes could hardly be higher in these defamation cases about a voting machine company in the 2020 election.