One core tactic in election deniers’ playbook is making false claims of voter fraud — and these are disproportionately aimed at cities with large populations of people of color. Such lies put the lives of election workers across the country at risk by spurring threats, harassment, and abuse. Election officials who serve communities of color, however, were disproportionately likely to be targeted by such attacks, according to the Brennan Center’s latest annual survey of election officials.

Following the 2020 election, Donald Trump’s campaign team filed dozens of lawsuits contesting the results. These efforts primarily focused on urban centers with larger shares of voters of color than surrounding communities. At a press conference in late November 2020, Trump’s personal attorney Rudy Giuliani cast doubt on results in the mostly Black city of Philadelphia by falsely claiming, “Unless you’re . . . stupid, you knew that a lot of people were coming over from Camden[, New Jersey,] to vote. They do every year. . . . And it’s allowed to happen because it’s a Democrat, corrupt city, and has been for years.” Such claims were echoed by outlets like Newsmax and other prominent election deniers, including Trump.

In Michigan, the campaign’s accusations of fraud centered on Detroit, where the population is nearly 80 percent Black, and not on nearby white counties where Joe Biden also won by significant margins. In Wisconsin, Trump singled out Milwaukee, which has the largest percentage of voters of color in the state. He accused the county of counting ballots slowly to perpetrate fraud, even though Wisconsin election officials are legally required to wait until Election Day to count mail-in ballots.

Given election deniers’ focus on sowing doubt about results in districts with mostly nonwhite populations, it stands to reason that the election officials working in these jurisdictions would face higher rates of abuse. The Brennan Center’s 2024 survey of election officials supports this conclusion. While it’s impossible to draw a direct line from these attacks to officials’ experiences, our data confirms that election officials serving those communities reported more intimidation and safety concerns.

Our survey found that 38 percent of all election officials reported experiencing harassment, abuse, or threats because of their job. More than a quarter of them are concerned about being assaulted at home or at work. These numbers were high across jurisdictions, regardless of their size or demographics, but they were particularly high in counties where a majority of residents were Hispanic or people of color.

Just over half of election officials who serve in these counties have been harassed or abused, compared to 36 percent of all officials. They are also twice as likely to have been threatened than their counterparts who serve in majority-white counties.

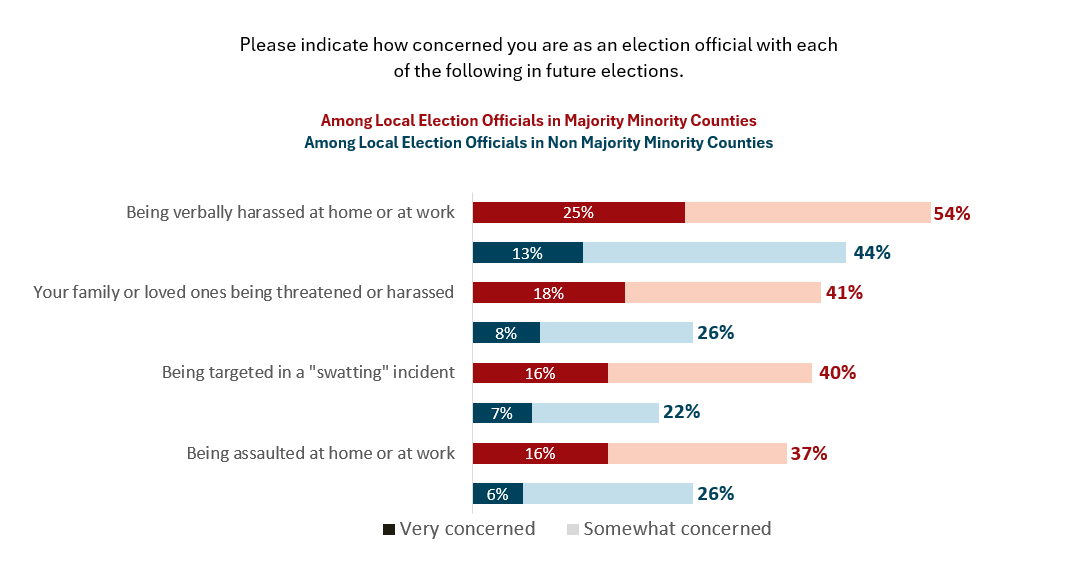

These trends remain consistent for other safety concerns. Election officials from counties where a majority of residents were Hispanic or people of color were more than twice as likely to report being very concerned about being assaulted at home or at work in future elections than the average election official, and nearly twice as likely to report being very concerned about being verbally harassed at home or at work. Forty-one percent of election officials serving counties with a majority of residents of color expressed concern about their family or loved ones being threatened or harassed, compared to 28 percent of all officials. They were also more concerned about being targeted in a “swatting” incident, with 40 percent expressing concern compared to 23 percent of all officials.

Georgia election workers Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss testified before the House January 6 Committee that after Rudy Giuliani publicly accused them of perpetrating election fraud, their lives changed overnight as they faced hundreds of threats. Freeman and Moss served in Fulton County, where a majority of residents are people of color.

As election officials have gone from working largely behind the scenes to perform the technical work of administering elections to being caught up in election denial, 70 percent said that threats have increased since the Big Lie of a “stolen” election originated in 2020. When leaders specifically target communities of color with false claims of fraud, the election officials who serve these communities become a target as well.

The Brennan Center has long advocated for adequate funding of elections to replace outdated voting machines and protect against insider threats. Election officials also need proper resources to implement critical security measures to enhance the safety of their staff. Officials serving counties with a majority of residents of color shoulder a disproportionate lack of funding: while 31 percent of all election officials said that their budgets need to grow significantly to keep up with administration and security needs, 55 percent of officials in communities of color reported the same. They also face more barriers, with 43 percent saying that they have had a budget request denied, compared to 25 percent of all election officials. (Election officials and their supporters can learn about how to access non-local funding for election security through the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections.)

With threats on the rise since 2020, proper election funding is needed now more than ever.