This article is adapted from When the Stars Begin to Fall: Overcoming Racism and Renewing the Promise of America, a book that outlines a path toward a multiracial national solidarity. It integrates personal narrative, rigorous historical and political analysis, and theories from sociology and political philosophy to make a compelling and aspirational case for a better America. By way of two personal vignettes, the excerpt below briefly introduces the tension between American ideals and the Black American experience. When the Stars Begins to Fall will be published on June 8 by Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.

I was 12 years old the first time someone called me a nigger.

It happened one autumn morning as I and my friends — four white boys and Marcus, a Black kid who had just moved to an adjoining neighborhood — trekked through our predominantly white suburban community nestled in the Piedmont plains of North Carolina. A small, nasally voice hurled the slur from behind a hedge of evergreen bushes as we crossed the trodden-grass clearing adjacent to our school. I immediately knew it was Cameron.

The air around 11-year-old Cameron was spoiled and self-obsessed, a characteristic that felt uncommon among the children in our subdivision. His signature tic was flipping his blond-frosted skater bangs over his head of brown hair — a peacock gesture that added some heft to his slight build. Sometimes his hotheaded ways caused him to spit fire that would eventually consume him in the backdraft. This was such a moment. The songs of the morning birds were interrupted as the n-word landed like a grenade in the middle of our unit. It had barely settled into the dirt beneath us when its heat singed the air between us. “All Black people are niggers!” The last syllable bounced around the trees behind us until it was rushed away by the breeze.

The unblinking eyes of my white friends all fell on me, their mouths agape. These were guys with whom I’d camped out, played basketball, traded baseball cards, and talked with endlessly about girls and professional wrestling. But they were not angry. They were not offended. They did not rush to my defense or to reassure me, as friends often do as a display of solidarity in moments like this. The only thing they had for me were slack-jawed expressions dotted with darting eyes that seemed to ask, “What’s our Black friend Teddy gonna do?” Standing there in my frail, prepubescent body, attempting to shoulder this new burden, I felt isolated and smothered, as if no one around could hear my muffled struggling. It was the first time I saddled the silent weight of being Black in America.

Then, in a flash of relief and with an oddly timed sense of joy, I remembered that I was not alone. The new kid! Marcus! In a single heartbeat, I turned to find him already moving toward Cameron’s hiding place in the hedges with choppy strides that quickly extended into a sprint. My instincts took over, and I launched with him. For some reason, it suddenly felt important to me that the two Black people within earshot acted together, in solidarity. Even though Marcus and I were only newly acquainted, in the face of racial hatred we found common cause and unified action. Running with him — my heart racing and my breath short and shallow between long strides — I still remember feeling strong . . . vibrant . . . affirmed.

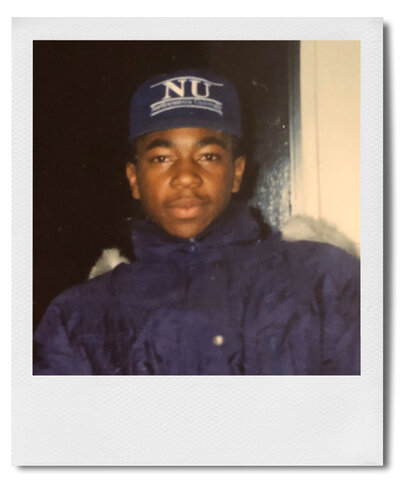

Thirty years later, on a crisp October morning in 2017, I was tucked into a beige-and-burnt-orange subway seat, rattling along the blue path of Washington, D.C.’s color-coded Metro line, deep in thought. If 12-year-old Teddy stepped into that train and eyed this older version of himself, he would have sneaked a steady stream of glances in search of something that felt familiar, trying to decide if he liked the man he had become.

He would have recognized the puffs of skin around the eyes that his mother’s family passed down like recipes and old wives’ tales; the prominent nose from his father’s lineage, born in a place where haints lurk in the crossings of darkened country fields; and his pigeon-toed mien that made his feet look as if they were continuously leaning in to whisper to each other, whether seated or in motion.

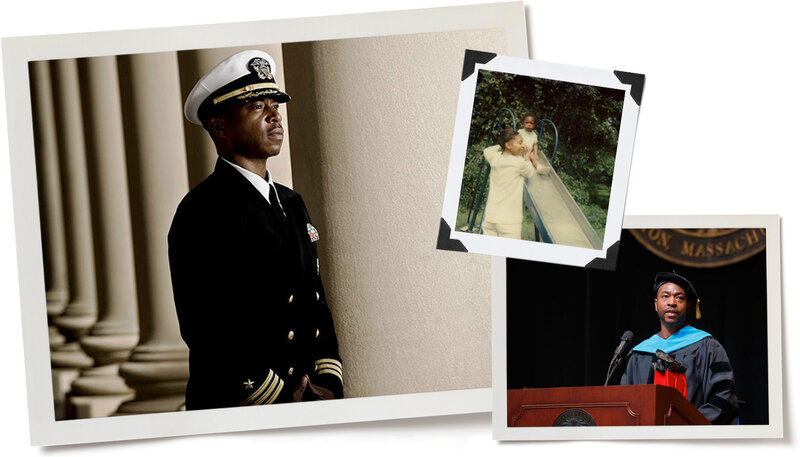

He would have noted the gold on the left hand and smiled to know that he would one day have a girl and find love. He never would have predicted the titles commander and doctor now preceding his last name, the receding hairline where there were once waves he brushed into uncooperative hair laden with pink lotion and pomade, or that he had traveled the world in suits and uniforms, from Johannesburg to Japan, war zones to the White House.

He definitely would have sensed the same melancholic insecurity that often grasps his adult pinky finger and tags along on all his life’s pursuits, little and large. And he would have noted that the burden he felt that one morning with Marcus and Cameron had doubled and transformed — the weight of race had evolved into a responsibility to America and to the dignity of its Black citizens. Had I caught his glance, perhaps I would have smiled, or simply just looked away. I was distracted. I had a speech to give.

There on the subway, I closed my eyes and mouthed the words of an address about the fate of our country. Five decades of alumni from the prestigious White House Fellowship program had gathered for the annual leadership conference in the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s august Hall of Flags, and I was one of the many speakers lined up to offer some thoughts on the state of our Union. Ben Carson, previously a Republican presidential candidate and secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, began the morning by assuring us that the nation was on the right track. Later, H.R. McMaster, then President Donald Trump’s national security advisor and a three-star Army general, took to the podium and sought to give us all confidence that the nation was safe. And then, when it was my turn, I looked the audience in the eye and told them America was in danger.

I began with the well-traveled story of Benjamin Franklin in 1787 emerging from the summer-long convening in Philadelphia, where our Constitution was put to paper. As Franklin stepped outside and took in a breath of fresh air, a woman approached and asked what sort of government the state delegates had created. Franklin responded wryly with a challenge: “A republic, if you can keep it.” Can we keep it? Racism, I told the room, was the only thing that has ever proved strong enough to break up the nation. If we fail to keep our republic, it will be because we allowed racism to swipe it from us once more.

I struggled through listing a sampling of racial incidents pointing to the fissures in our republic: protests and riots in Black communities after lethal confrontations between unarmed Black people and police officers; white nationalists marching with Nazi Germany and Confederate battle flags declaring America belongs to them alone; Black athletes and white politicians at war over appropriate displays of patriotism and free speech during the national anthem; and increased vitriol between political parties accompanied by the racial sorting of party membership.

But I also needed my audience to understand what racism felt like — how it shaped a different reality for one of their Black peers. So I told them: America is where I have achieved dreams that would have been impossible elsewhere, but it is also a haven for my deepest disappointments. It is where the color of my skin enters the room before I do, crashing the party and casting a shadow over conversations. It is where military men who are supposed to be my brothers in arms tell me that my promotions are affirmative-action handouts. It is where I have been yanked from my car, handcuffed, searched, and tossed in jail because two cops thought a Black guy with a blown headlight was suspicious. It is where I raise sons who cannot escape airings of shaky smartphone videos showing Black people’s deadly encounters with law enforcement: George Floyd. Philando Castile. Eric Garner. Walter Scott. And so many others. And it is where I have had to explain to them why their brown skin and dreadlocks make them prime candidates to be excluded from the full rights and protections of citizenship.

Clockwise from left: Courtesy of Harvard University; Courtesy from author; Courtesy of Northeastern University.

Clockwise from left: Courtesy of Harvard University; Courtesy from author; Courtesy of Northeastern University.

Despite maddening contradictions, I love America. I simply cannot help it. I told the room that there is an undeniable and admirable strength in a nation that slowly but steadily groans toward the incorporation of those it used to exclude. It is a country founded on high-minded ideals with an aspirational, hopeful orientation propelled by a people who believe it will be better tomorrow than it is today. For two decades, I wore a military uniform, proudly pulling the cloth of the nation over my shoulders each morning with the full understanding that many people suffered and died for me to have the honor. An appreciation of how far the United States has come, coupled with the vision of what it can become, should inspire us to do our part so that future generations can experience a more perfect union than we have. It is imperfect, but it is ours.

I should not have been startled when a sudden and familiar force tugged at the corners of my face after I asked the room if our republic was one that we could keep. My throat tightened, choking off the words trying to push through. My eyes warmed. My vision blurred. Drawing from my last ounce of composure, I told the mostly white, mostly conservative, and mostly middle-aged audience that racism was an existential threat to America. If we could not muster the bravery to figure out and confront our racial issues, there would be no United States worth saving to leave to our children.

Then a tear fell. And then another. I bowed my head, ashamed of the public surrender to emotion. After a couple of seconds and some deep breaths while pinching at the bridge of my nose, I lifted my head to find, much to my surprise, that many in the chamber were in tears, too.

My tears were the product of a lapse of optimism and faith in the American idea. A naive revelation, perhaps, for a grown Black man. But for the first time in my life, it dawned on me that the nation might be more wedded to racial hierarchy than to the founding principles I had sworn to support and defend as an officer in the U.S. Navy. And I realized that the feeling sweeping through me was the polar opposite of the strength and purpose that had flooded my 12-year-old body after an 11-year-old called me the n-word. Race is at the root of both the empowering connections and the debilitating disconnections that characterize our American experience. Sitting with these two feelings in the same moment on a stage one block from the White House, I worried that we may not be capable of overcoming the effects of racism or the animus it pollinates. I worried that we may not be truly committed to keeping the republic.

The weeping faces that October morning in the nation’s capital were proof that I was not alone. Americans of all races, ages, and political leanings share the deep concern that an inability to resolve our racial issues may be our undoing. All of our tears carried a question: What is to be done? My tears, however, also contained an answer — an answer that has been passed down through generations of Black experiences in America and that has slowly but relentlessly pushed the nation closer to its professed ideals: solidarity.

Back on that autumn morning of my youth when the n-word knocked the wind out of me, Marcus and I chased Cameron, but we did not catch him before he reached the school grounds. That afternoon, however, saw a different result. Cameron and Marcus crossed paths on the way home and immediately engaged in a profane war of words, calling each other everything but a child of God until the kindling caught fire in a series of blows. The two fought their way through the subdivision: throwing punches in a neighbor’s yard and trampling her tulips, swinging wildly at each other in the street and up into driveways like a caravan of chaos, and even knocking an American flag to the ground—the stars falling and settling in the dirt to be trampled by an adolescent interracial conflict.

Decades later in the Chamber of Commerce’s Hall of Flags, I tearfully concluded my address to a room of White House Fellows by recalling the gold sun etched into the back of the chair that seated George Washington during the 1787 Constitutional Convention. The sun was bisected by an imagined horizon, giving the illusion that it was either on its way up into the sky or descending to give way to the stars. As the delegates made their way to sign what would become our Constitution, Benjamin Franklin remarked, “I have often looked at that behind the President without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting: But now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting Sun.”

Under the sweltering suns of an America unrealized, many Black people toiled under the lash to help build a nation. Forbidden to sing of the freedom their souls demanded, they turned to Christian themes to cloak their hearts’ desire. Substituting visions of a heavenly rapture for their dreams of emancipation, they devised spirituals that famed sociologist and historian W.E.B DuBois called the nation’s first original music — the “sorrow songs.” One such song chronicled the rising sun, symbolizing the end of one day and the beginning of another:

My Lord, what a morning

My Lord what a morning

My Lord, what a morning

When the stars begin to fall.

When I descended the stage, I stumbled a bit. After awkwardly taking a few steps to regain my balance, David, a white retired Air Force pilot with silver hair, caught me in a bear hug next to the American flag that bordered the stage. I could not help thinking of what the generations before us would have thought of this fleeting moment of connection and unity, especially the generations of my family filled with sturdy men and women from the red clay of Georgia and the tobacco fields of South Carolina who had endured the nation’s worst impulses just so I would have a fighting chance at the Promise. If my name is any indication, they would have seen a rising sun — a reason to continue hoping that racial equality lies ahead. Whether it is indeed setting or rising, however, will depend on our ability to find the solidarity charted in the pages ahead.