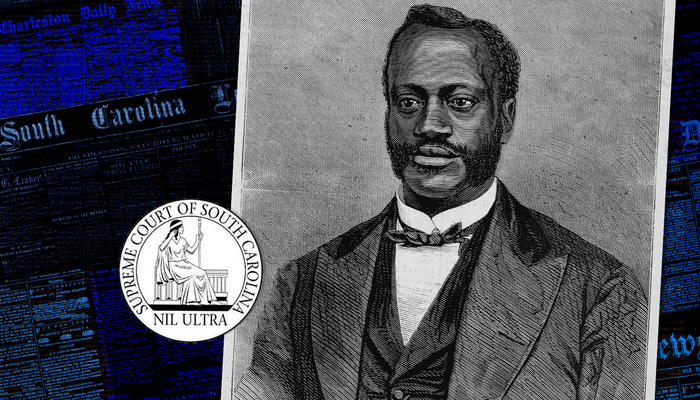

Jonathan Jasper Wright, the country’s first Black state supreme court justice, was sworn into his seat on the South Carolina Supreme Court in 1870. A second Black justice did not reach a high court bench in any state until nearly a century later, when Otis Smith joined the Michigan Supreme Court in 1961.

Wright’s tenure was intertwined with the rise and fall of Reconstruction in the South, a period when Black Americans temporarily gained legal and political opportunities that would be stripped after a campaign of white political violence surrounding the 1876 election and the installation of President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1877. As a political leader and a justice, Wright contributed to the creation and interpretation of new state laws, defining — and surprisingly, sometimes narrowing — the rights of recently freed Black South Carolinians. But he was forced to resign amid scandal when Reconstruction ended, many say unfairly.

Wright was an attorney from Pennsylvania and the son of two formerly enslaved parents. He traveled to South Carolina in 1866 as an employee of the Freedmen’s Bureau, providing legal assistance to formerly enslaved people in the state and eventually becoming a prominent political and legal figure.

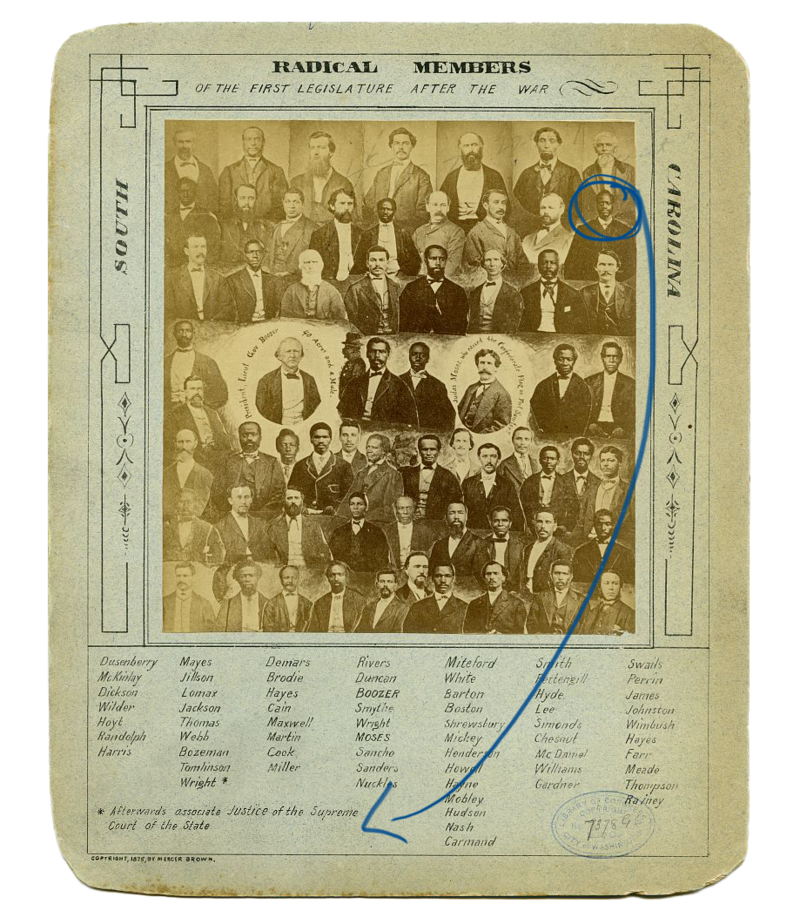

Wright and another Black attorney, William Whipper, were the first Black attorneys to appear before a legal tribunal in South Carolina. Wright also served as a delegate to the South Carolina state constitutional convention in 1867, ran and lost a campaign for lieutenant governor in 1868, and shortly after was elected as a state senator. He was among nine others who were South Carolina’s first Black state senators.

In February 1870, Wright was elected by the state legislature to fill a vacancy on the South Carolina Supreme Court. Wright, considered the more conservative candidate, ran against and defeated William Whipper, who had support from radical Republicans. Strikingly, Wright’s tenure on the court included several rulings that restricted the rights of Black South Carolinians. Many of these decisions conflicted with the political commitments he had expressed as a delegate to the constitutional convention and as a state senator. In the case of Russell v. Cantwell, for example, a freed Black man accused a white man of malicious prosecution that had occurred before the Civil War. Wright denied the claim, arguing that formerly enslaved people did not gain rights retroactively after emancipation and warning against the “flood of litigation” that would ensue if such remedies were made available.

One of Wright’s most noteworthy votes was in dissent against the validation of unverified election results. The 1876 general election, in South Carolina and across the South, had been preceded by a campaign of voter intimidation and violence orchestrated by white Democrats. Despite credible reports of ballot box stuffing and voter suppression on Election Day, Democrats petitioned the South Carolina Supreme Court to prohibit the state Board of Canvassers from investigating the validity of the election results. The court sided with the Democrats, with Wright in dissent. Following a series of events which involved jailing the Republican members of the Board of Canvassers for contempt of court, Democratic and Republican candidates for the state legislative and gubernatorial races both declared electoral victory.

Democrat Wade Hampton’s claim to the South Carolina governorship ultimately reached the South Carolina Supreme Court indirectly, in the case of Ex Parte Norris. At issue was Hampton’s purported pardon of prisoner Tilda Norris. In a 2–1 ruling with Wright in dissent, the court ruled that the pardon was legitimate, thereby validating Hampton’s claim to the governor’s seat. Wright’s dissent was met with outrage: a local newspaper asked, “[Was] it right, Wright, for you to take your salary with your left hand while you denied the Governor’s right with your right?” In February 1877, on the same day as the Ex Parte Norris decision, the Electoral Commission formally voted to recognize Rutherford B. Hayes as the next president of the United States and federal lawmakers agreed to remove federal troops from the South, a compromise that led to the end of the era of Reconstruction.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The tide turned quickly against Wright. In May 1877, the new Democratic majority in the state legislature passed a resolution calling for an investigation into him. The legislative committee tasked with investigating Wright heard testimony asserting that he had accepted a bribe to change his vote in a case, but it never found evidence proving this claim. After 10 days of secret hearings, the committee presented a resolution calling for impeachment, citing accusations of “drunkenness.” Amid impeachment proceedings, Wright resigned.

These accusations followed Wright for the rest of his life. Upon his death in 1885, a national legal journal published an announcement reading, “it is scarcely necessary to say that his published opinions do not give evidence of much legal learning or ability.” Later, historians questioned these allegations: in 1933, Robert Woody wrote in an essay about Wright that “there are several factors which lead to the conclusion that Wright was not guilty of the charge.” More recently, historians have documented a broad effort to discredit the accomplishments of Black leaders during the Reconstruction era. One modern historian of post-Reconstruction historical writing noted that “African American accomplishments were ridiculed or ignored altogether, while racist-inspired terrorism was white-washed.”

Wright played a critical role in establishing South Carolina’s legal structure during a period of revolutionary change to American democracy. His removal from the court resulted in part from a campaign of white voter intimidation and electoral fraud, which led to Democrats regaining control of the legislature. For decades, his legacy was diminished and largely written out of history, as was the experience of many Reconstruction-era Black leaders and politicians.

Almost 150 years after Wright’s impeachment, with a lack of diversity on state supreme courts still a serious problem, his complicated legacy as a trailblazing jurist remains timely.