I. Introduction

The values that undergird American democracy are being tested. As has become increasingly clear, our republic has long relied not just on formal laws and the Constitution, but also on unwritten rules and norms that constrain the behavior of public officials. These guardrails, often invisible, curb abuses of power. They ensure that officials act for the public good, not for personal financial gain. They protect nonpartisan public servants in law enforcement and elsewhere from improper political influence. They protect businesspeople from corrupting favoritism and graft. And they protect citizens from arbitrary and unfair government action. These practices have long held the allegiance of public officials from all political parties. Without them, government becomes a chaotic grab for power and self-interest.

Lately, the nation has learned again just how important those protections are — and how flimsy they can prove to be. For years, many assumed that presidents had to release their tax returns. It turns out they don’t. We assumed presidents would refrain from interfering in criminal investigations. In fact, little prevents them from doing so. Respect for expertise, for the role of the free press, for the proper independent role of the judiciary, seemed firmly embedded practices. Until they weren’t.

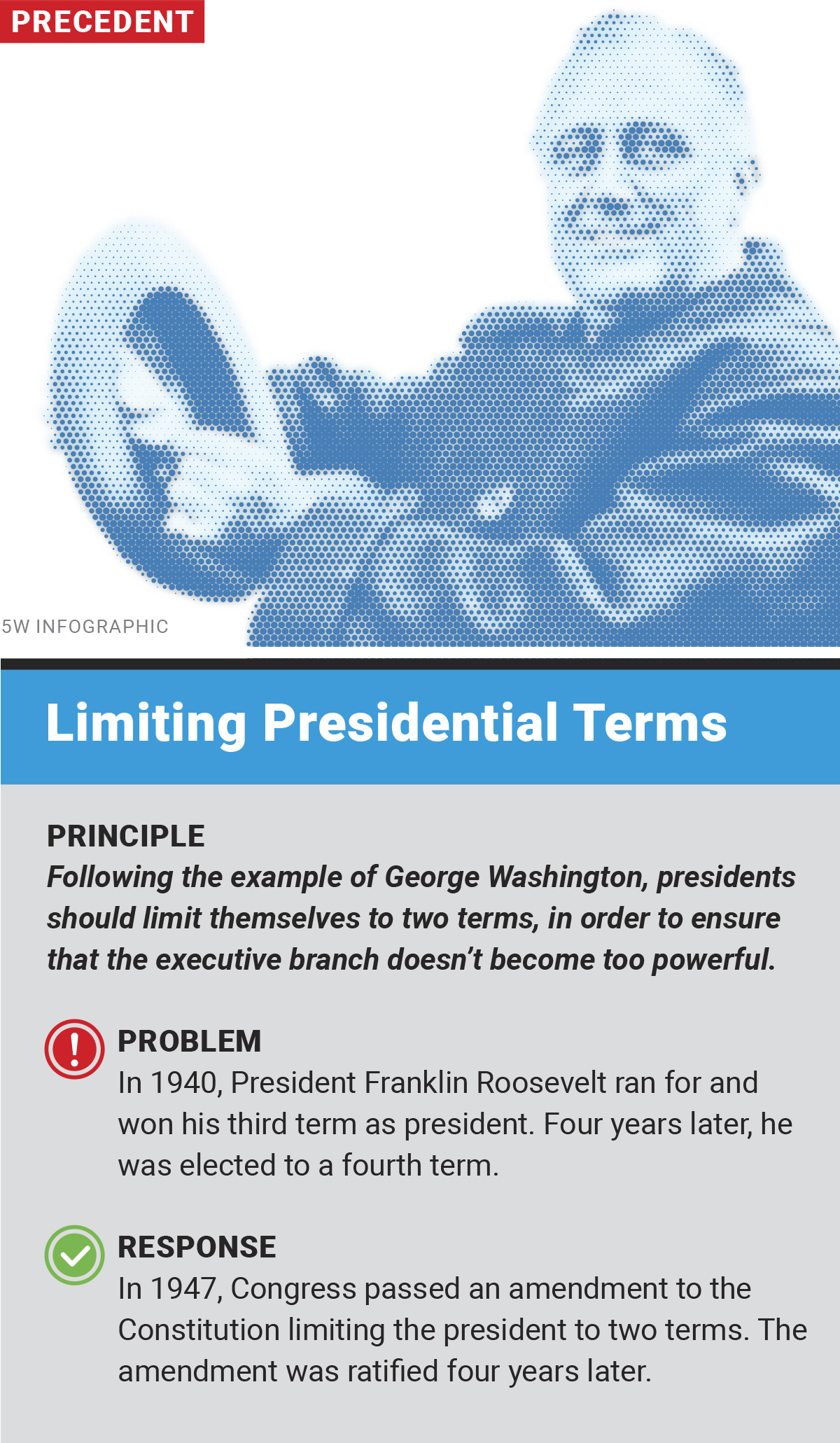

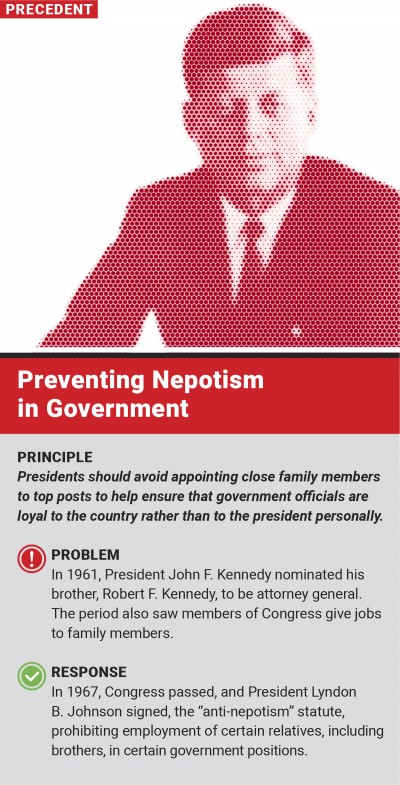

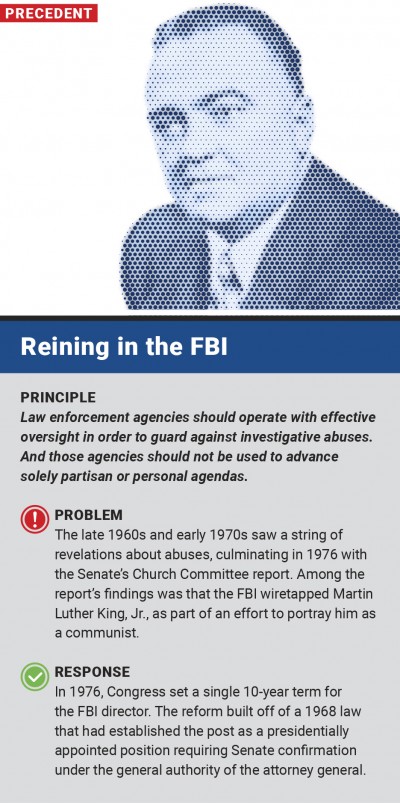

Presidents have overreached before. When they did so, the system reacted. George Washington’s decision to limit himself to two terms was as solid a precedent as ever existed in American political life. Then Franklin D. Roosevelt ran for and won a third and then a fourth term. So, we amended the Constitution to formally enshrine the two-term norm. After John F. Kennedy appointed his brother to lead the Justice Department and other elected officials sought patronage positions for their family members, Congress passed an anti-nepotism law. Richard Nixon’s many abuses prompted a wide array of new laws, ranging from the special prosecutor law (now expired) to the Budget and Impoundment Control Act and the War Powers Act. Some of these were enacted after he left office. Others, such as the federal campaign finance law, were passed while he was still serving, with broad bipartisan support, over his veto. In the wake of Watergate, a full-fledged accountability system — often unspoken — constrained the executive branch from lawless activity. This held for nearly half a century.

In short, time and again abuse produced a response. Reform follows abuse — but not automatically, and not always. Today the country is living through another such moment. Once again, it is time to act. It is time to turn soft norms into hard law. A new wave of reform solutions is essential to restore public trust. And as in other eras, the task of advancing reform cannot be for one or another party alone.

Hence the National Task Force on Rule of Law and Democracy. The Task Force is a nonpartisan group of former public servants and policy experts. We have worked at the highest levels in federal and state government, as prosecutors, members of the military, senior advisers in the White House, members of Congress, heads of federal agencies, and state executives. We come from across the country and reflect varying political views. We have come together to develop solutions to repair and revitalize our democracy. Our focus is not on the current political moment but on the future. Our system of government has long depended on leaders following basic norms and ground rules designed to prevent abuse of power. Unless those guardrails are restored, they risk being destroyed permanently — or being replaced with new antidemocratic norms that future leaders can exploit.

We have examined norms and practices surrounding financial conflicts, political interference with law enforcement, the use of government data and science, the appointment of public officials, and many other related issues. We have consulted other experts and former officials from both parties. Despite our differences, we have identified concrete ways to fix what has been broken.

We begin with those norms. What are they? And why do they matter?

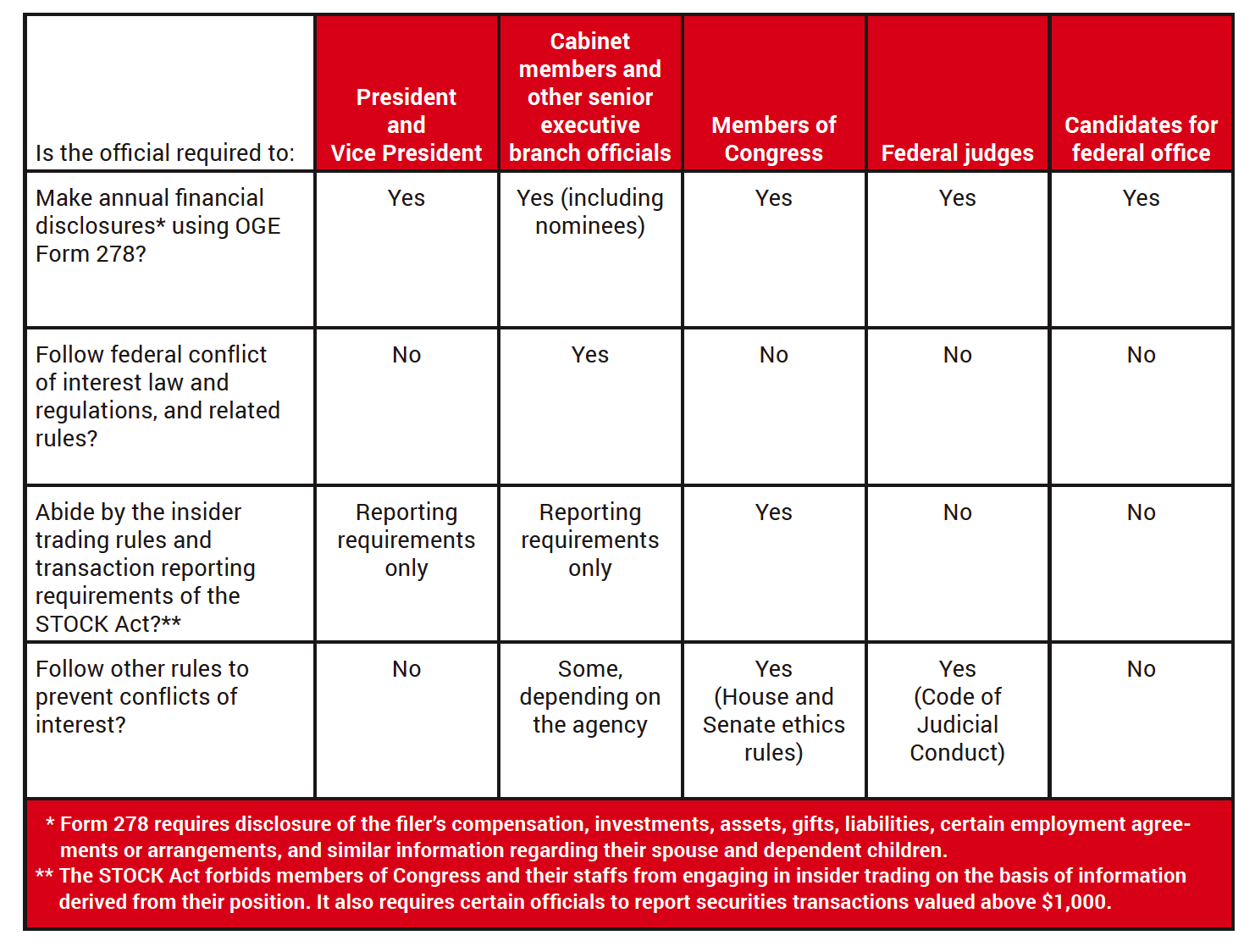

Checks and balances. The phrase appears nowhere in the Constitution, but it is central to blunt arbitrary power and the potential for tyranny. footnote1_gNnYsTTkUtOB5Bg0BX43OXy1r14-c7DvtLbmodAB7Vc_lmwbm0j619Ll1 The Federalist No. 51 (James Madison) (“In a single republic, all the power surrendered by the people is submitted to the administration of a single government; and the usurpations are guarded against by a division of the government into distinct and separate departments.”). It’s more than the clockwork mechanism of three separate but coequal branches. Checks have evolved within each branch as well. Congressional ethics committees police improper conduct. footnote2_awxpsH2E7ZpQwOucJ3tjGnJBos0JUskKAZJj3OyYpM_x7YPHehYWn3n2 S. Res. 338, 88th Cong. (1964) (establishing a Select Committee on Standards and Conduct in the Senate); “Senate Committee Reorganization,” Congressional Record, vol. 123, Feb. 1, 1977, p. 2886 (creating a permanent Select Committee on Ethics to replace the Select Committee on Standards and Conduct); H.R. Res. 1013, 89th Cong. (1966) (establishing a Select Committee on Standards and Conduct in the House of Representatives); H.R. Res. 418, 90th Cong. (1967) (establishing a Committee on Standards of Official Conduct in the House of Representatives); H.R. Res. 895, 110th Cong. (2008) (establishing an independent Office of Congressional Ethics in the House of Representatives). Courts operate under a self-imposed code of conduct. Chief judges, circuit judicial councils, or the Judicial Conference investigate allegations of wrongdoing. footnote3_FLHeUZk4KEFNbakcvyMjHJ29Kk29I5RJeDU6dT3qiE_eFQuAFeNfacO3 “Code of Conduct for Judicial Employees,” in Guide to Judiciary Policy, Administrative Office of the United States Courts, 2013, available athttp://www.uscourts.gov/rules-policies/judiciary-policies/code-conduct/code-conduct-judicial-employees. The executive branch has standards of ethical conduct, as well as inspectors general, internal auditors, and the Justice Department’s special counsel regulations. These overlapping safeguards check the conduct of the powerful.

An evenhanded and unbiased administration of the law. The awesome power of prosecution must be wielded without consideration of individuals’ political or financial status, or their personal relationships. This precept has deep roots. It draws from British law. Its violation formed a chief complaint in the Declaration of Independence. And it was woven into America’s Constitution in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, with their promise of “equal protection” and “due process of law.”

Public ethics. Officials are obliged to seek the public good, not private gain. The Constitution includes key anti-corruption provisions, such as the Emoluments Clauses that prevent a president from receiving funds from foreign governments or states. The Framers had a broad view of corruption. To them, it meant a public official serving some other master — whether pecuniary or political — rather than the public.

Respect for science and the free flow of information. In a modern economy, data — whether environmental, demographic, or financial — must be trustworthy. Beginning especially in the 1970s, an expectation of government transparency — and transparency of government data — became standard. And throughout the nation’s history, the accountability provided by a sometimes ferocious free press has been regarded as crucial.

We believe these values are more than fussy political etiquette. They are, in fact, vital to our democratic institutions and necessary to restore public trust. We hope that the reflexive partisanship of our age does not pose an insurmountable obstacle. At other times of reform, Americans from across the ideological spectrum, including members of both parties, have come together to restore and repair public institutions. Despite today’s intense partisan polarization, we believe that our great nation can and should similarly achieve consensus for reform. In fact, we believe these values still command deep allegiance from Americans across the political spectrum. Our nonpartisan work has reinforced this view. It is up to patriots from all parties to work together on behalf of what we believe to be core precepts of our democracy.

“We the People” gave our government its power. That notion made American democracy, imperfect as it was, truly revolutionary from the start. Restoring these principles is central to the task of revitalizing democracy itself.

With these values in mind, the Task Force examined some of the most significant current areas of concern where our democratic system is most under pressure from official overreach.

In this report, we put forward specific proposals in support of two basic principles — the rule of law and ethical conduct in government.

In future reports, we will turn to other areas, including issues related to money in politics, congressional reform, government-sponsored research and data, and the process for appointing qualified professionals to critical government positions. Most of our proposals reflect a decision to make previously longstanding practices legally required. They reflect, we believe, an existing consensus across both parties.

Ethical Conduct and Government Accountability

To ensure transparency in government officials’ financial dealings:

-

Congress should pass legislation to create an ethics task force to modernize financial disclosure requirements for government officials, including closing the loophole for family businesses and privately held companies, and reducing the burdens of disclosure.

- Congress should require the president and vice president, and candidates for those offices, to publicly disclose their personal and business tax returns.

- Congress should require a confidential national security financial review for incoming presidents, vice presidents, and other senior officials.

To better ensure that government officials put the interests of the American people first:

- Congress should pass a law to enforce the safeguards in the Constitution’s Foreign and Domestic Emoluments Clauses, clearly articulating what payments and benefits are and are not prohibited and providing an enforcement scheme for violations.

- Congress should extend federal safeguards against conflicts of interest to the president and vice president, with specific exemptions that recognize the president’s unique role.

To ensure that public officials are held accountable for violations of ethics rules where appropriate:

- Congress should reform the Office of Government Ethics (OGE) so that it can better enforce federal ethics laws, including by:

- granting OGE the power, under certain circumstances, to conduct confidential investigations of ethics violations in the executive branch,

- creating a separate enforcement division within OGE,

- allowing OGE to bring civil enforcement actions in federal court,

- specifying that the OGE director may not be removed during his or her term except for good cause,

- providing OGE an opportunity to review and object to conflict of interest waivers, and

- confirming that White House staff must follow federal ethics rules.

The Rule of Law and Evenhanded Administration of Justice

To safeguard against inappropriate interference in law enforcement for political or personal aims:

-

Congress should pass legislation requiring the executive branch to articulate clear standards for, and report on how, the White House interacts with law enforcement, including by:

- requiring the White House and enforcement agencies to publish policies specifying who should and should not participate in discussions about specific law enforcement matters,

- requiring law enforcement agencies to maintain a log of covered White House contacts and to provide summary reports to Congress and inspectors general.

- Congress should empower agency inspectors general to investigate improper interference in law enforcement matters.

To ensure that no one is above the law:

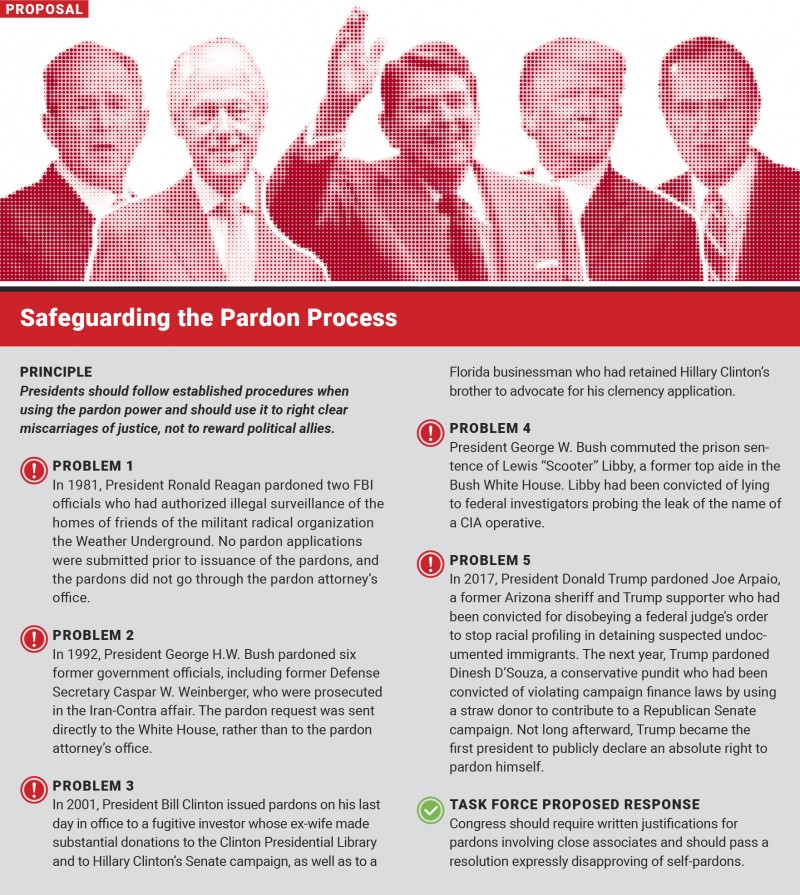

- Congress should require written justifications from the president for pardons involving close associates.

- Congress should pass a resolution expressly and categorically condemning self-pardons.

- Congress should pass legislation providing that special counsels may only be removed “for cause” and establishing judicial review for removals.

End Notes

-

footnote1_gNnYsTTkUtOB5Bg0BX43OXy1r14-c7DvtLbmodAB7Vc_lmwbm0j619Ll

1

The Federalist No. 51 (James Madison) (“In a single republic, all the power surrendered by the people is submitted to the administration of a single government; and the usurpations are guarded against by a division of the government into distinct and separate departments.”). -

footnote2_awxpsH2E7ZpQwOucJ3tjGnJBos0JUskKAZJj3OyYpM_x7YPHehYWn3n

2

S. Res. 338, 88th Cong. (1964) (establishing a Select Committee on Standards and Conduct in the Senate); “Senate Committee Reorganization,” Congressional Record, vol. 123, Feb. 1, 1977, p. 2886 (creating a permanent Select Committee on Ethics to replace the Select Committee on Standards and Conduct); H.R. Res. 1013, 89th Cong. (1966) (establishing a Select Committee on Standards and Conduct in the House of Representatives); H.R. Res. 418, 90th Cong. (1967) (establishing a Committee on Standards of Official Conduct in the House of Representatives); H.R. Res. 895, 110th Cong. (2008) (establishing an independent Office of Congressional Ethics in the House of Representatives). -

footnote3_FLHeUZk4KEFNbakcvyMjHJ29Kk29I5RJeDU6dT3qiE_eFQuAFeNfacO

3

“Code of Conduct for Judicial Employees,” in Guide to Judiciary Policy, Administrative Office of the United States Courts, 2013, available at http://www.uscourts.gov/rules-policies/judiciary-policies/code-conduct/code-conduct-judicial-employees.