While 2030 may seem far away, the Census Bureau has already begun to prepare for the next decennial count. As part of its preparations, the bureau invited public comments for improving its research and design processes. Comments that have been disclosed so far show broad agreement on issues that the bureau should tackle and a chorus of support for reforms that would enhance the accuracy, equity, and legitimacy of the count.

Differential undercounts

Differential undercounts have been a long-standing issue in the census, and concern about their effects on the accuracy of the 2020 results is widespread. While the census typically counts the total number of people living in the country accurately, it has historically undercounted many communities of color and overcounted white communities. The bureau’s major quality checks on the 2020 census showed that it faced the same serious data problems as past counts, with people identifying as Black, Hispanic, or Native American experiencing particularly marked undercounts.

A broad cast of stakeholders ranging from civil rights organizations to leading statisticians submitted comments urging the bureau to limit undercounts going forward. Their recommendations emphasize the importance of community input at every stage of the census process, from early research and design to data collection to data processing.

The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, for example, encouraged the bureau to partner with community representatives to research improved messaging and advertising campaigns targeted at undercounted groups. The Leadership Conference also suggested that the bureau identify ways to increase the census’s accessibility to language minorities and people with disabilities — including by expanding the number of languages the census is offered in and developing text and verbal assistance for people who need accommodations.

Stakeholders have also suggested technological fixes. The Center on Data Innovation, for example, encourages the bureau to use third-party data sources, such as IRS tax filings or private commercial data, to fill in missing demographic information.

Questionnaire design

The comment letters also display related concerns that the design of the census questionnaire itself poses obstacles to an accurate and equitable count. For example, in its current configuration, the census does not allow people to describe their identities as they understand them. This is particularly the case when it comes to their race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. Currently, the census treats race and ethnicity as two separate questions and provides limited options for certain racial or ethnic groups. The form does not ask any questions about gender and sexuality. These limitations result in certain groups going undercounted and others becoming statistically invisible.

Stakeholders have suggested concrete solutions to address these concerns. For example, the Movement Advancement Project — leading a group of 28 signatories that includes the Brennan Center — recommends the bureau include a sexual orientation and gender identity question in the 2030 Census and launch public education programs to increase census participation by LGBTQI+ people.

Other comment letters, such as that from the Funders’ Committee for Civic Participation, recommended that the bureau to continue to research and test combining its separate race and ethnicity questions into a single Hispanic origin, race, and ethnicity question — a process that would lay the groundwork for changes to the census form for 2030.

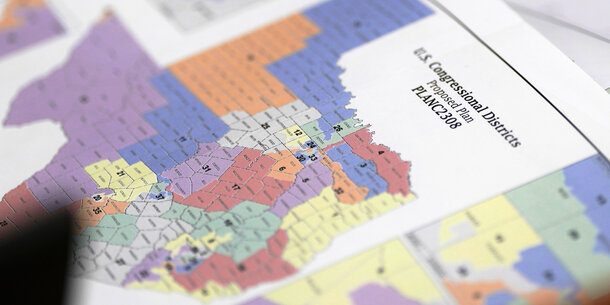

Prison gerrymandering

The comments also show deep concern with the bureau’s contributions to prison gerrymandering. The census counts incarcerated people in the places where they are imprisoned rather than to their pre-incarceration homes. Electoral districts drawn using the bureau’s data shift political resources away from communities of color and reallocate them to the predominantly white, rural areas where prisons tend to be located.

For decades, stakeholders have advocated for changing this practice so incarcerated people are instead counted at their home addresses. The Prison Policy Initiative, writing on behalf of 26 criminal justice and voting rights organizations, recommended the bureau research counting methods and other data sources — like administrative data sets — that could support that goal.

• • •

The comments discussed here were all directed to the bureau. But Congress has a role to play in improving the census, too. The Brennan Center’s report on improving the census details steps Congress can take to address these and other problems. These include passing legislation to give the bureau more latitude to experiment with methods to cure undercounts, facilitating changes to the census questionnaire and the bureau’s data-gathering processes through its oversight function, and legislatively amending the bureau’s residence rule, among other proposals.

Legal and operational changes are both necessary for long-term change, and they should be implemented in parallel to improve future censuses. Community groups are voicing a need for long-overdue reform — both the bureau and Congress should take heed.