New population estimates from the Census Bureau point to significant changes in the composition of the House after the 2030 census.

Using the new data, the Brennan Center estimates that if trends of the last two years continue, the South will gain nine seats in the reapportionment of congressional districts after the next census — the largest single-decade gain for the region in history.

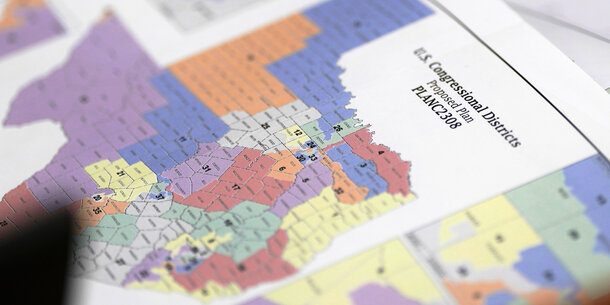

Florida and Texas could see especially large increases of four seats each, with Texas within striking distance of adding a fifth seat. North Carolina would also see its congressional delegation increase by a seat.

These potential gains are driven overwhelmingly by communities of color. Census data released over the summer shows that between 2022 and 2023, more than 84 percent of population growth in the South came from increases in the region’s Black, Latino, and Asian populations, with more than half of overall growth coming from Latinos. The majority of this growth, moreover, was in just four states: Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas.

Meanwhile, California and New York, which have seen significant population outflows this decade, are projected to lose four and two districts respectively. For California, this would be only the second time in its history it has lost representation (the first was this decade when the Golden State lost one seat).

Based on current data, Illinois, Minnesota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin would all see one-seat decreases.

If these estimates come to pass, the South would have a record 164 seats in the House next decade, a profound change. After the 1960 reapportionment, the South, Midwest, and Northeast each had roughly the same number of representatives. But with country’s steady population shift southward in the years since, nearly 4 in 10 members of the House could well be southerners by next decade.

These big apportionment changes would also significantly change political parties’ Electoral College math starting with the 2032 election.

In 2024, Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris could have won the Electoral College by winning the states she carried, Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District (Nebraska allocates some electoral votes by district), plus the so-called Blue Wall battleground states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

By 2032, that strategy would no longer work. Given the shift of electoral votes to the South, even if a Democrat in 2032 were to carry the Blue Wall states and both Arizona and Nevada, the result would be only a narrow 276–262 win.

Of course, the projections are not set in stone. With half a decade to go before the next census, much could change.

The new Trump administration, for example, could carry through on campaign promises to deport millions of undocumented immigrants and their families. Or, as some allies want, it could adopt an even more hardline approach that sharply reduces the number of foreign student visas and cuts off other pathways for legal immigration. Both moves would affect the population of immigrant-heavy states, red and blue alike.

Likewise, the flow of Americans out of states like California, New York, and Pennsylvania in recent years could slow — or even partially reverse. Indeed, the most recent census data contains signs that may be happening to some degree. If population changes for the rest of the decade look more like the past year, California and New York would lose three seats and one seat, rather than four and two.

The outcome could also turn on something more basic: an accurate census. In the lead up to the 2020 census, states like California and New York invested millions of dollars to educate residents about the census and the importance of participation. Other states, like Texas, invested nothing or very little. As a result, New York lost fewer seats than projected, while Texas gained fewer than expected.

An additional wildcard could be a decision by the Trump administration to try to add a controversial question to the census requesting the citizenship status of respondents, which advocates warn could depress census participation in states with large immigrant communities. Efforts last decade by the first Trump administration to add such a question were blocked by courts because officials rushed efforts and didn’t follow required administrative procedures, but many are urging another, better-organized try.

But even if the precise state-level shifts could be affected by a variety of factors, the broad contours of likely changes seem clear enough. Halfway to the 2030 census, next decade is shaping up to be one that will bring some of the most significant shifts in political power in the country’s history.