This was originally published in the Hill.

This fall, all 99 seats in Ohio’s House of Representatives are up for election. Voters should be seeing an exciting, unpredictable campaign season unfold, with candidates vying to address their needs.

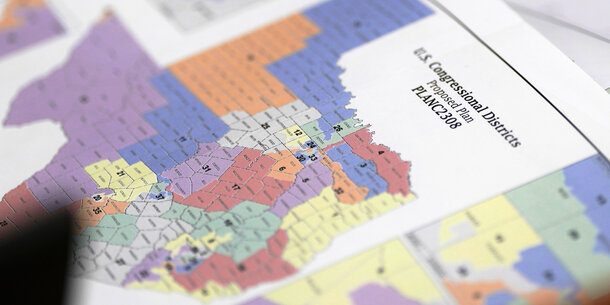

That’s not happening. Because of the way the powerful lawmakers and political insiders drew the district lines, victory is all but guaranteed for many candidates, months before Election Day.

This is nothing new for Ohio voters, and they’ve had enough.

This summer, 535,005 voters backed a ballot initiative to remove gerrymandering from Ohio politics for good. The measure has qualified to be Issue 1 in November, but politicians have put an obstacle in its way: A distorted and deceptive description of the measure that will appear on the ballot.

On Monday, Citizens Not Politicians — the coalition behind the initiative — sued for accurate language. My organization, the Brennan Center for Justice, is a member of the coalition.

Of course, Ohio isn’t the only state subject to extreme gerrymandering. Voters in a handful of other states will see races on the 2024 ballot that are already all but decided because politicians controlled the map-making process and used it to guarantee their own political futures.

In our democracy, it is perhaps the clearest example of letting foxes guard hen houses. We shouldn’t let the legislators who benefit most from gerrymandering draw district maps.

In Ohio, the Citizens Not Politicians ballot initiative would address this problem and take the power to draw district maps away from the state’s most powerful politicians and give it to an independent commission made up of Ohio citizens.

This constitutional amendment, if approved, would end secret backroom negotiations to carve up the state and handshake deals between political power brokers and lobbyists. Instead, Ohio voters who do not stand to personally gain from mapping outcomes would draw districts that represent community preferences as opposed to politicians’ desires.

It would allow elections to respond to ebbs and flows in partisan preferences so that when voters swing toward Republicans or Democrats election results do as well — something Ohio hasn’t had in at least 15 years.

To make this a reality, the commission would do its business in full public view with direct input from Ohioans, a significant and necessary departure from the status quo. Not so long ago, politicians, partisan operatives and lobbyists worked in a secret hotel room dubbed “the Bunker,” drawing district maps that carved up the state to incumbents’ advantage.

Even after public outcry forced politicians in Ohio to amend the constitution in 2015 and 2018, those changes amounted to little difference at the end of the day. The same politicians kept the redistricting pen. And as before, maps continued to be drawn in secret and unveiled at the last possible moment, at times as public hearings were already underway.

Put simply, Ohio lawmakers have proven repeatedly that they will stop at nothing to gerrymander the state and insulate themselves from voters.

In 2022, the Ohio Supreme Court ordered lawmakers to redraw their district maps in a lawsuit brought by the Brennan Center on behalf of the Ohio Organizing Collaborative and other groups in the state. These maps carved up communities and did not reflect the partisan preferences of Ohio voters, a violation of the Ohio constitution. Instead of complying with the highest court in the state, the politicians in control of redistricting ignored the order, producing maps that had superficial differences but made no attempts to comply with the law.

The court rejected those maps, and once again, the lawmakers defied the order. In total, the Ohio Supreme Court struck down district maps seven times between 2022 and 2023 to no avail. For the 2022 election, Ohio voters used unconstitutional maps that the Ohio Supreme Court struck down. Current district maps in place for 2024 are no better.

The Ohioans who signed the petition on behalf of the ballot measure represent both parties, independents and all parts of the state. They want to break the cycle of unjust maps, once and for all. They want to decide who represents them in the legislature and Congress.

They want their votes to matter.