Lauren-Brooke Eisen is the senior director and Ram Subramanian is the managing director of the Brennan Center’s Justice Program. They describe a new initiative to fundamentally change the experience of incarceration to one that is more constructive and humane.

What principles does a dignity-first approach to incarceration entail?

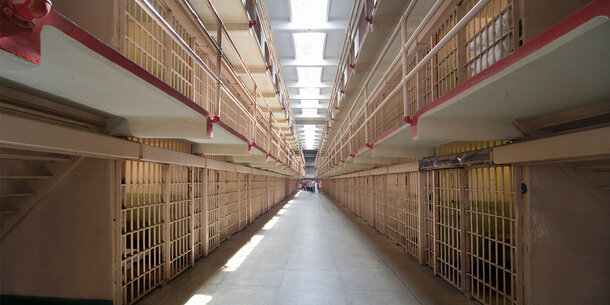

The twin organizing principles are normalization and rehabilitation. Life inside prison should approximate life outside as much as possible. This means giving people access to education, recreation, and treatment; maximizing their interactions with family and friends; and allowing them a certain amount of autonomy in their daily activities. Currently, life in American prisons is characterized by total, all-encompassing control: the prison dictates the activities someone is allowed to do, the treatment they may receive, where they are allowed to go in the facility, even where they walk along a corridor.

Incarceration should enable people to lead a life of social responsibility after release, which requires a recognition that people can change. Providing productive and meaningful activities, such as education or work opportunities with fair compensation, is central to this new approach. In many northern European countries, incarcerated people have their own rooms with a private bathroom, and they often have a key to their living area. Corrections staff are encouraged to engage with them, share meals with them, and see them as human beings.

What are the biggest obstacles to implementing this approach here?

Northern Europe uses prisons sparingly; the United States has more than 1.2 million people in prison and more than half a million in local jails. Each of the 50 states and the federal government manage their own prisons, which makes it difficult to overhaul correctional culture writ large.

Implementing a new corrections philosophy in the United States is challenging because institutional culture is very ingrained. In American prisons, anti-fraternization policies regulate contact between staff and prison residents, either limiting or altogether prohibiting interactions between corrections employees and incarcerated people. The U.S. corrections culture is focused primarily on security and discipline.

Additionally, corrections officers in the United States often receive only weeks of training — usually focused only on safety, security, and control — whereas northern European corrections staff get multiple years of training that focuses on social and behavioral management of human beings and includes topics such as psychology, social education, and human rights. Trainings stress a therapeutic approach to correctional management that emphasizes positive reinforcement and prioritizes strategies to defuse tension and de-escalate dangerous situations.

What types of programs and innovations has your team seen so far?

The programs and units we have visited reimagine the relationship between corrections officers and those who are incarcerated. In Washington State and Oregon, the non-profit organization Amend brings a public health mindset to changing the culture in U.S. prisons. In Indiana prisons, the Last Mile runs coding and web development programs. We also spent time in Connecticut and North Dakota with staff and incarcerated people in the Restoring Promise initiative, which creates housing units for young adults where they receive coaching from incarcerated people over the age of 25 on financial literacy, conflict mediation, and other supports to improve reintegration into their communities when released from prison.

Our visits also took us to Pennsylvania, where we learned about the Little Scandinavia unit, which is modeled after prisons in Norway. Residents live in single-person rooms, share a kitchen, have access to outdoor green space, and go to work, treatment, and school across the facility. Officers on the unit act more like counselors than prison guards, sharing meals and giving advice. We were struck by the incredible partnerships that have developed between correctional leaders, researchers, and techni – cal assistance providers despite challenging politics both inside corrections departments and in state legislatures.

What do you hope to achieve with your forthcoming report?

People say that prison reform in the United States is unachievable. This report will rebut that assumption. There are many ways to approach reform. It can happen in select units but also in whole facilities. We hope that the report will inspire others to make further investments. Educating the public about how improving conditions can reduce violence in both prisons and jails and in the broader community will be central to reforming the U.S. correctional model.