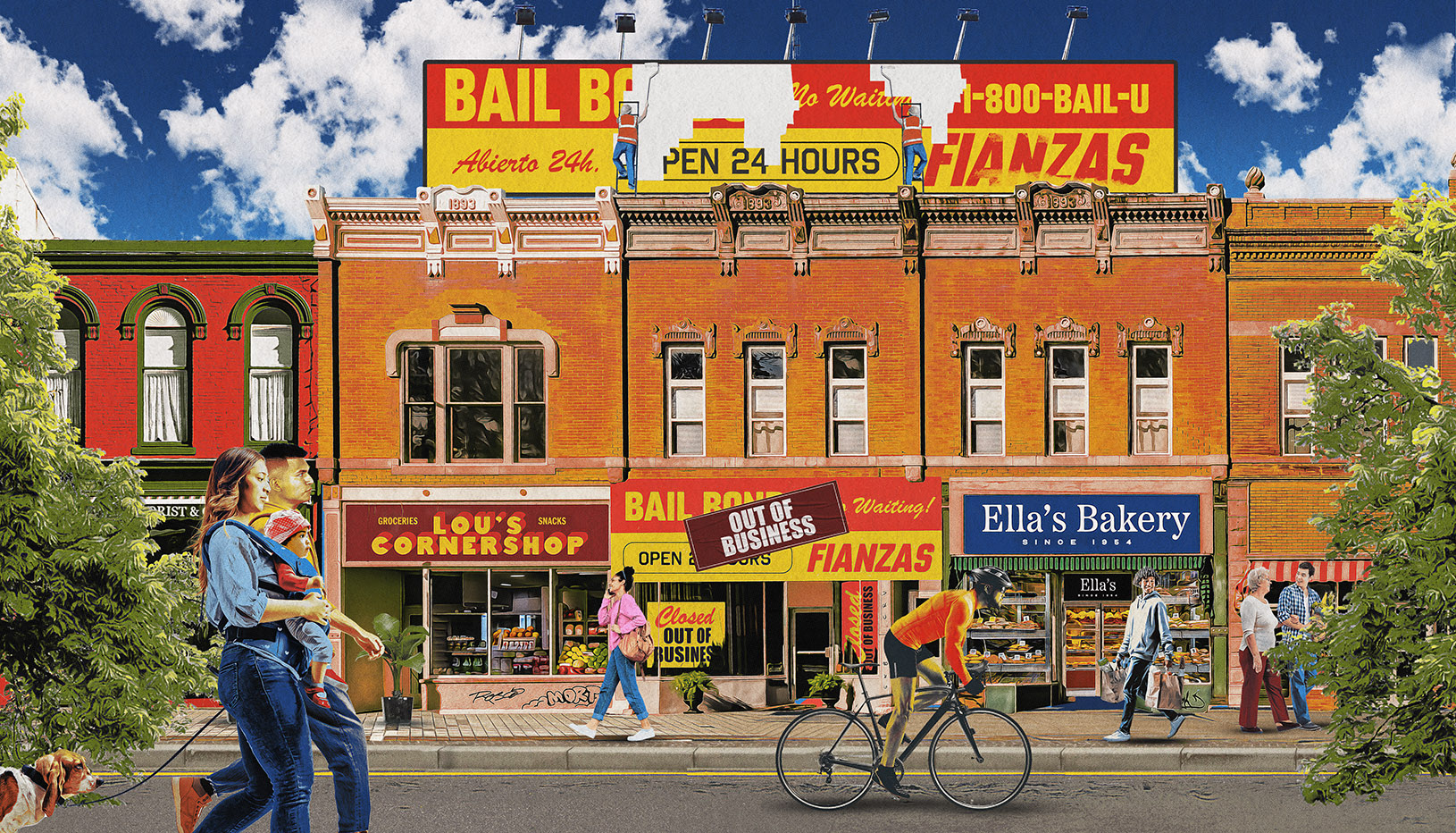

Does Bail Reform Impact Crime?

The evidence for a connection between bail reform and crime is weak. Here’s how we know.

A growing number of cities and states are working to reduce their reliance on money bail, reflecting larger efforts to cut down on unnecessary incarceration and make the criminal justice system fairer. But misconceptions about how these reforms impact crime often block progress. A new report by Brennan Center Justice Program Senior Counsel Ames Grawert and Economics Fellow Terry-Ann Craigie offers the most wide-ranging study of the issue so far, finding no evidence that bail reform affects crime rates. The authors discussed their approach to the research and unpacked the significance of their findings in an interview.

Why study the relationship between bail reform and crime rates?

Craigie: There are numerous reasons we want bail reform. Ideally, we want to keep people out of jail who don’t belong there and save the state funds by avoiding unnecessary incarceration. But it’s crucial to study the relationship between bail reform and crime rates to ensure that these policy changes don’t lead to unintended negative consequences.

Grawert: We were also drawn to this research because bail reform has emerged as a flashpoint in political debates about the criminal justice system, with bail reform often serving as the opening salvo in a broader attack on criminal justice reform. It’s important to determine whether these critiques are valid, as good policy should be guided by research.

If the attacks on bail reform were justified, we would need to reconsider our strategy. On the other hand, if there is no merit to them, it’s all the more important to have a response to critics that shows there are better ways to improve public safety than to roll back reforms. This goes back to a Brennan Center report my former colleague Stephanie Wylie and I coauthored called Challenges to Advancing Bail Reform. We found that in states like New York, Utah, and Alaska, where bail reform faced significant backlash, the political attacks always outran the ability of researchers, advocates, and think tanks to assemble data in defense of policy, which is frustrating.

Basically, while data is important to conversations about bail reform, it takes time to gather that data. So we hope our new report helps fill in the gaps for policymakers looking to understand what effects bail reform may have in their jurisdiction and better inform debates around these policies.

What sets your study apart from existing research?

Grawert: The big distinction is that a lot of the other solid work on bail reform has tended to focus on single jurisdictions. So, what are the effects of bail reform in New York? Or what are the effects of bail reform in Houston? Those are valuable questions, but if you want to try to get a big picture of bail reform’s effects, you need a lot more data. That’s what our report tries to do.

The broad scope of our study is beneficial from an analytical standpoint too. Many bail reform policies went into effect in or around 2020, which makes it hard to tease apart the effects of bail reform from the effects of the pandemic and other things that happened that year. By using a much larger sample, we can be more statistically rigorous and try to control for those factors.

Craigie: Another important distinction is that our study looks at multiple measures of crime rates, not just one. We looked at overall index crime rates, which encompass murder, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft, and larceny, as well as the specific categories of violent crime, property crime, and larceny. And what we found is that bail reform does not significantly impact crime rates one way or another in any of these categories.

Grawert: I want to emphasize that we didn’t only look at crime rates before and after bail reform. We developed a very thorough and careful method to determine the extent to which any changes that we observed in crime rates were caused by bail reform, statistically speaking.

What are the challenges involved in analyzing the impact of bail reform on crime rates?

Craigie: I don’t even know where to start with that! The challenges begin with data. It’s very difficult to get consistent and reliable crime data across different cities, which made compiling our dataset a challenge. We used public data sources for some cities, including city-level public safety data portals and the Crime Open Database. For others, we had to request data directly from the cities. Then we had to ensure that the measures for crime were consistent across all cities.

Grawert: It’s almost impossible to overstate how difficult it is to get standardized crime data across cities. While the FBI notionally standardizes data on this group of top offenses called index crimes, the data from individual cities is produced before that standardization. For instance, what New York City considers an assault may not be the same as what New Orleans considers an assault. To make sure we were comparing apples to apples, we had to create internal definitions for assault and the other offenses we studied. Then we had to go through all the incidents reported by cities and determine which ones matched our internal definitions. Any incidents that didn’t fit were excluded from our dataset.

This data-collection challenge is related to a broader concern the Brennan Center has highlighted: the lack of timely and reliable crime data produced by the FBI. We needed data at a monthly level to get as many observations as we could to power our statistical model, but the FBI only had annual data for most of the cities we studied, and it had no data whatsoever for certain cities in key years.

Ours is the sort of paper that is going to get easier, I think, as the FBI improves its crime-reporting practices, but the current state of things made this research a real challenge and meant that data collection was a huge first leg of the project.

Craigie: Another challenge is it’s hard to build a model examining the causal relationship between bail reform and crime rates. Descriptive analyses can give us a general picture of whether crime trends changed after a city implemented bail reform. But measuring whether those changes can actually be attributed to bail reform and nothing else requires more sophisticated methods, which we used in our report.

Crime rates are influenced by many complex factors. Since we studied the period from 2015 through 2021, we had to account for the impact of the pandemic and associated lockdown measures. Aside from that, we had to control for socioeconomic factors like average income, unemployment rates, education, and so on, in order to isolate the specific impact of bail reform from the other variables that might affect crime.

Walk us through your dataset. How did you select which cities and offenses to look at?

Grawert: To an extent, our city selection was guided by which cities had useable data. As I explained earlier, not every city publishes crime data regularly. So we had to go where the data was.

Craigie: Specifically, we needed cities with available data from 2015 through 2021. The data also had to be granular enough for us to clean and analyze effectively. These requirements meant our study mostly focused on large cities.

Grawert: That’s appropriate for a study like this, though, since the largest cities in the country are generally the ones implementing or affected by bail reforms. Once we had a sample that we felt was broad and deep enough, we sought to fill out the national picture with missing states and regions. Then we ensured that the sample represented cities that we knew had major bail policy changes but didn’t necessarily have easily accessible data, as was the case with Newark, New Jersey.

As for offenses, we concentrated on major offenses tracked by the FBI. The reason why is simple enough: we could be reasonably confident that any city that reports crime data would publish data on those offenses. To our surprise, however, several cities did not publish data on sex offenses, meaning we had to exclude them from the study. That’s unfortunate, as these are serious offenses that are important to understand. But it was the only option we felt was available to us given the data-quality issues we encountered.

How did you analyze the data and check the validity of your results?

Craigie: We used what is called a difference-in-differences framework to measure the effect of bail reform on crime rates. This means we examined crime trends before and after bail reforms in 22 cities and compared these with trends in 11 cities without reforms. We found no significant changes in crime trends during the 12 months after reform, which indicates that bail reform does not have a discernible impact on crime rates.

To make sure we could reliably attribute any significant deviations in crime trends to bail reform rather than preexisting differences, we selected reform and non-reform cities that had nearly identical crime trends in the six months before reforms were implemented.

However, this analysis was complicated by the fact that the cities we studied implemented reforms at different times. We addressed this issue, which is called a weighting bias, by using a statistical estimator that accounts for staggered policy adoption. Even still, we found that bail reform doesn’t change crime trends in a statistically significant way.

We also accounted for potential outliers that may have skewed our results. We reran our models multiple times and removed a different city each time to ensure our findings remained consistent. Finally, we tested the theory that more robust bail reforms may impact crime and examined only cities with major reforms — Buffalo, New York; Chicago; Houston; New York City; and Newark. Again, this didn’t change our findings.

Grawert: We aimed to use the data to check as many “theories” as possible of how bail reform might be linked to crime. We wanted people to come away confident we’ve checked every angle. This was especially critical because previous Brennan Center research shows that some bail reforms don’t have the effects that people expect. For example, reforms in some cities ended up increasing the use of pretrial detention. This prior work made clear the importance of testing different types of reforms, especially those that have been shown to significantly affect who gets assessed bail. That’s what encouraged us to break out reforms by how they were implemented — be it by courts, legislators, or prosecutors — and evaluate whether our results changed based on those categories. They did not.

What other research do you think is needed to better understand the relationship between bail reform and crime?

Craigie: I think a study that encompasses all the major U.S. cities is warranted. Our study, though quite extensive with its analysis of 33 cities, is still limited since major cities were still excluded, such as Miami, Jacksonville, Indianapolis, and San Antonio. If cities like these were included, the results may yield different findings. Additionally, it would be useful to study a longer time period to rule out the possibility that bail reform has long-term impacts on crime.

Grawert: I also think it would be valuable to get a better sense of the many complex factors that influence recidivism while on pretrial release so that we are better able to control for them in other research on bail reform. Future studies can try to account for that complexity by looking at data on, for example, how often judges actually set bail and how long people remain in detention between arrest and the end of their case. But that data is most often controlled by court systems and tends to be even harder to access than crime data. Some of my Brennan Center Justice Program colleagues have worked with court data, as have other researchers, and this is an exciting area of potential research on bail policy.