The past decade has seen increasing momentum for bail reform, with lawmakers, prosecutors, and courts across the country shifting the focus of bail decisions from ability to pay to fairness and public safety. However, reformers must frequently contend with fears that limiting or eliminating money bail will lead to a rise in crime. The data shows that these fears are unfounded, and they shouldn’t stand in the way of reforms that can make our criminal justice system more equitable and humane.

What is bail?

When someone is arrested, they may be given the option to post bail, which allows them to be released from custody while awaiting their court proceedings. Bail was originally meant to ensure that the accused would return to court for their hearings and trial, and today it often works by requiring a financial guarantee. This is why the terms bail and money bail are used interchangeably much of the time.

In cases involving money bail, the court has broad discretion to set a dollar amount that a person accused of a crime must pay to secure their release before trial. If a person misses their court date, they lose the money, and the court may issue a warrant for their arrest. If they appear as promised, they usually get the money back, minus fees, which can be quite high if they use a bail bondsman.

Not all bail involves money, however. The court can choose to release a person on their own recognizance, for instance, meaning they only need to provide a written promise to appear in court when required. The promise can also be backed by an “unsecured” bond — that is, a promise to forfeit some amount of money if they break their conditions of release. In those cases, people released on an unsecured bond will only be asked to pay the court if they miss any scheduled appearances or break the other conditions of their pretrial release.

While the right to bail is enshrined in 41 state constitutions, this right is not absolute. People may be denied bail depending on the type of crime they’re accused of or whether they’re deemed a flight risk. In recent decades, many states have also allowed courts to deny bail to those who are considered an immediate risk to public safety. The rules governing bail eligibility and bail amounts differ across states.

Why do bail policies need to be reformed?

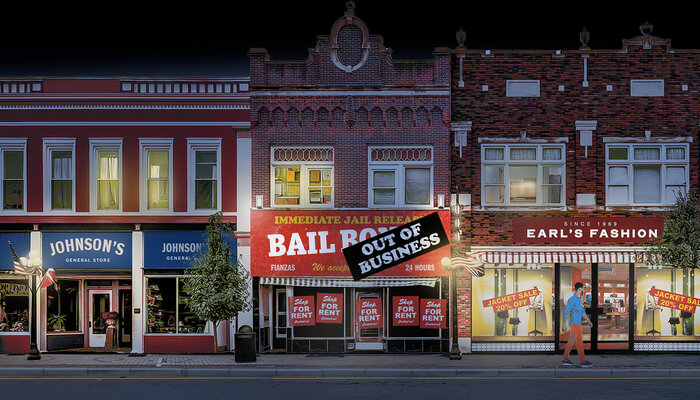

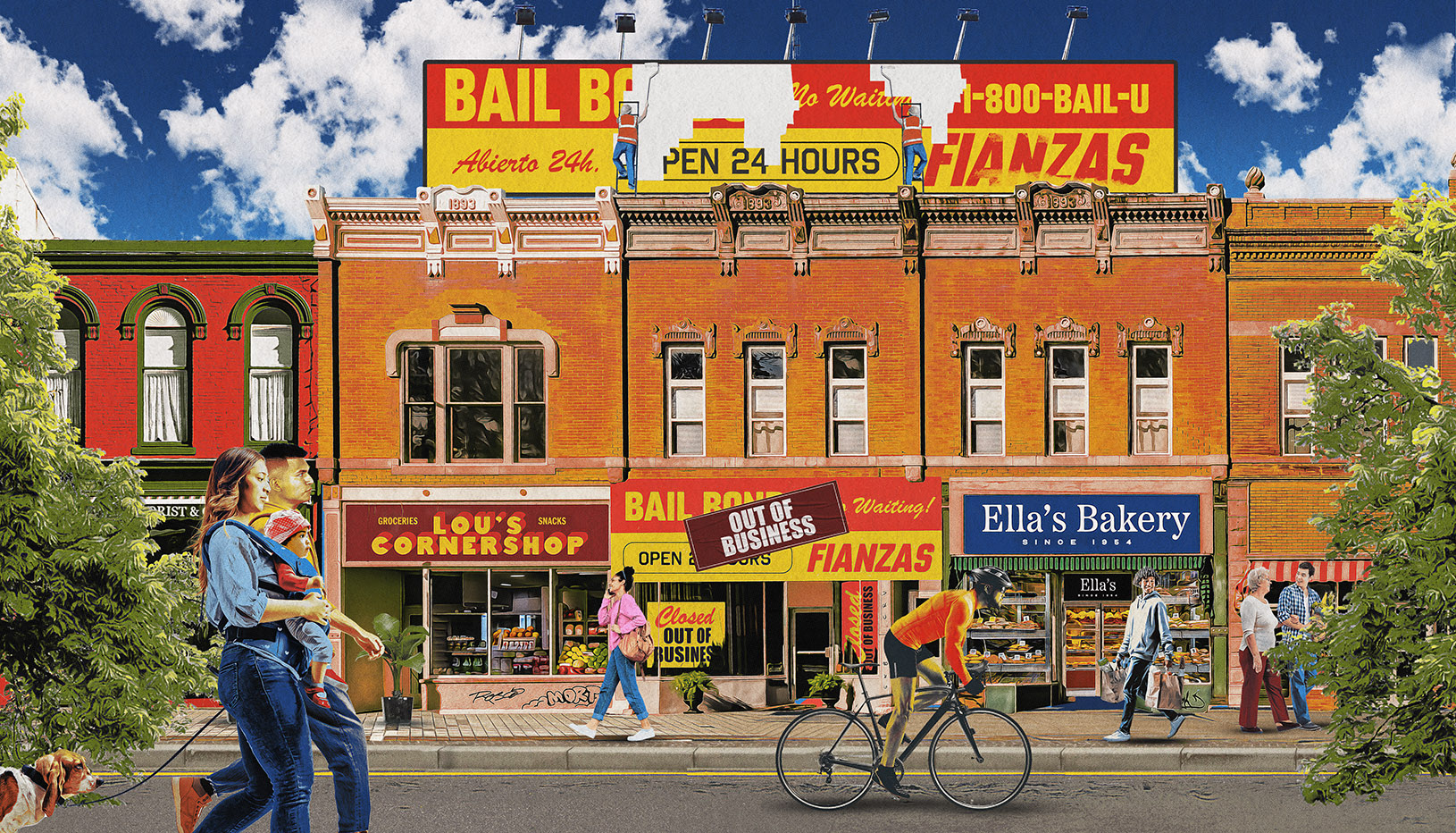

Money bail has faced intense criticism for decades, and for good reason. The system effectively punishes poverty by creating a two-tiered system where ability to pay, rather than public safety, determines who stays in jail and who goes free.

Those who can’t afford their bail are left with a grim choice: remain behind bars, sometimes for months or even years, until trial or contract with a commercial bail bond company. Staying in jail can severely disrupt a person’s life, leading to job loss, family strain, and increased pressure to accept plea deals, regardless of whether they are guilty. The alarmingly high number of deaths by suicide in pretrial detention speaks to its psychological toll. On the other hand, the financial repercussions of a commercial bail bond can be overwhelming. These companies offer to cover the bail amount in exchange for a hefty fee, which is typically a percentage of the total bail, and a high-interest repayment plan. The result is a profit-driven industry that extracts billions from low-income Americans, deepening the cycle of poverty and incarceration. At the same time, people with sufficient wealth or access to credit can buy their freedom.

The racial disparities within the bail system exacerbate the problem. Black and Latino defendants are frequently assessed higher bail amounts than white defendants charged with similar crimes. Systemic inequalities make it even harder for people of color to afford bail, contributing to disproportionately high rates of pretrial detention among these communities.

Bail reform seeks to address these issues and explore more equitable approaches to pretrial release and detention. Some jurisdictions have curbed money bail to ensure that only those who genuinely pose a risk of fleeing or endangering the public are held in custody. Over the long term, such reforms aim to reduce unnecessary incarceration and mitigate racial and economic disparities.

Where has bail reform been implemented?

New York and New Jersey are some of the most-cited examples of states that passed laws designed to dramatically overhaul their bail systems. Their efforts to move away from money bail sparked backlash, leading legislators to roll back some of the changes. Nevertheless, bail reform hasn’t been confined to so-called blue states. Over the past decade, more than a dozen cities and states across the political spectrum, from California to Texas, have taken steps to limit or eliminate money bail.

The specifics of these reforms vary. Some jurisdictions have restricted money bail to cases where defendants are deemed a significant flight risk or threat to public safety. Others have enacted laws that prevent judges from setting money bail for lower-level offenses, such as violations or misdemeanors. Additionally, some jurisdictions require judges to consider a defendant’s ability to pay when setting bail amounts.

The push for bail reform has come from several fronts: state legislatures, courts, and prosecutors. In New York State, for example, a 2020 law restricted the circumstances when money bail could be used. In Houston, a court ruling effectively eliminated money bail for low-level misdemeanor cases; in Los Angeles and San Francisco, district attorneys directed prosecutors to avoid seeking money bail in certain cases and opt for nonmonetary conditions instead. While changes enacted by legislatures tend to be the most robust and have the greatest impact on bail systems, all three of these fronts have helped grow the momentum for bail reform nationwide.

What are common critiques against bail reform?

Opponents frequently attack bail reform with unsubstantiated claims that it drives crime, pointing to high-profile cases where people released on bail committed new offenses. They argue that reducing the use of money bail makes it too easy for potentially dangerous individuals to be released, thus compromising public safety.

These concerns deserve careful consideration, as criminal justice policies should be based on robust evidence of their effectiveness at preserving public safety. However, isolated incidents of crime don’t mean that bail reform broadly increases crime.

Is bail reform impacting crime rates?

In the most comprehensive study of the issue to date, Brennan Center researchers found no evidence that bail reform affects crime rates.

The study analyzed monthly crime data from 33 cities from 2015 through 2021, comparing 22 cities that implemented bail reforms with 11 that did not. It looked at murder, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft, and larceny to determine if there was any increase or decrease in these crimes after cities enacted bail reforms.

The researchers performed several different analyses of the data to assess any potential connection between bail reform and crime.

They examined whether bail reform affected crime rates generally. If bail reform were causing an increase in crime, as critics have claimed, we would expect to see crime rates in cities with bail reform rise compared to non-reform cities. However, a simple comparison shows no such thing. Instead, crime rates remained broadly similar in both sets of cities throughout the study period; crime dropped for both groups during 2020 at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, driven by falling larceny rates, and then rose in subsequent years, without significant deviation between the two groups.

While informative, this type of comparison may mask differences between the groups of cities. As such, Brennan Center researchers undertook a more sophisticated analysis of the data in which they studied changes in crime rates in the 12 months after cities enacted bail reforms. To ensure that any differences in post-reform crime trends were likely due to the reforms themselves rather than underlying differences between the cities, they matched reform and non-reform cities that had similar crime trends in the six months before bail reforms were enacted. And they accounted for variables such as the timing of bail reforms, socioeconomic factors, political orientation, and pandemic-related lockdown measures. They found that in the 12 months after reforms were implemented, crime trends in the reform cities and the comparable non-reform cities didn’t deviate in a statistically significant way.

These results remained true when they looked separately at violent crimes, property crimes, as well as larceny, which covers lower-level misdemeanor offenses like shoplifting. The data did not show that bail reform had an impact on any of these crime types in the 12 months following reform.

Even when focusing on cities with major bail reforms — Buffalo, New York; Chicago; Houston; New York City; and Newark — the study found no significant change in crime trends in the 12 months after the policy changes compared to cities without reform.

Taken together, the study’s conclusion is clear: there is no evidence linking bail reform to changes in crime rates. This undercuts the politicized claims that bail reform is responsible for recent crime spikes.

These findings are reliable, as researchers conducted various additional tests to validate their results, accounting for potential delays in reform implementation, the impact of the pandemic, or any outliers in their data that could have skewed their findings. Even after considering these factors, the results consistently showed that bail reform did not have a discernible effect on crime rates.

If bail reform doesn’t seem to be impacting crime rates either way, why pursue it?

According to the best data we have, bail reform neither increases nor reduces crime rates. So why opt for reform? It boils down to a simple reason: bail reform is about creating a fairer and more equitable criminal justice system.

Without a compelling public safety justification, punishing people before they’re convicted is fundamentally unfair and undermines the principle that people are presumed innocent until proven guilty. By reducing reliance on money bail, reforms aim to tackle these disparities and offer a more humane approach to pretrial release. These changes are one step in a broader reckoning with a criminal justice system that is widely recognized as excessively punitive and driven by problematic for-profit incentives.

Evidence consistently shows that the current bail system deepens social inequalities, with poorer defendants and people of color bearing the brunt of its flaws — not because they’re guilty, but because they can’t afford to buy their release.

Additionally, while bail reform may not impact crime rates directly, it could indirectly play a role in advancing long-term public safety goals. By removing the focus on whether someone can pay bail, judges can instead prioritize safety when deciding whether a person should await their trial in jail or in their community.