This is an excerpt from The People’s Constitution: 200 Years, 27 Amendments, and the Promise of a More Perfect Union. The book tells how the American people have taken an imperfect constitution — the product of compromises and an artifact of its time — and made it more democratic.

In the five years following the Civil War, Americans added three Reconstruction amendments to the U.S. Constitution, amendments that served as the cornerstone for the nation’s “second founding.” The Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery in 1865, was a powerful affirmation of the individual liberty and human dignity of four million Black people held in bondage in America — a constitutional reform that forever changed their fate and that of their descendants. The Fourteenth Amendment, enacted three years later, guaranteed equal citizenship and provided strong new protections for civil rights. But what about the political rights of the newly freed? With defiant white Southerners already taking steps to restore society as it existed before the war, there was a renewed sense of urgency to safeguard the newly-bestowed constitutional rights, increasing the pressure on Congress to act. Yet even many of the most ardent congressional supporters of equal rights questioned whether the country was ready to extend the franchise to the former slaves.

To address this pressing concern, lawmakers would have to revisit one of the crucial compromises made by the Constitution’s Framers. While one delegate to the Philadelphia Convention remarked, “The people will not readily subscribe to the new national Constitution, if it should subject them to be disenfranchised,” most of the men who devised our system of government back in 1787 believed that voting should be restricted to males who owned property or paid certain taxes. In the end, the Framers made the fateful decision to leave it to each state to determine who qualifies as a voter. Throughout the nation’s history, states would exercise this power to exclude African Americans, women, Indigenous people, immigrants, religious minorities, and others from equal participation in our democracy. Even today, many states continue to use this power to erect barriers to the ballot box that disproportionately impact voters of color.

It was 1869, and the clock was ticking. The 40th session of Congress would soon come to a close. Would lawmakers seize the moment to take bold action to protect voting rights?

Back in the spring of 1866, as the Senate was making the final set of changes to the Fourteenth Amendment, Charles Sumner proposed adding a provision to outlaw racial discrimination in all “civil or political” rights “whether in the courtroom or at the ballot-box.” The proposal was voted down overwhelmingly. As Jacob Howard later explained on behalf of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction: “It was our opinion that three-fourths of the States of this Union could not be induced to vote to grant the right of suffrage . . . to the colored race.” Apart from Sumner, few political leaders were willing to champion Black suffrage publicly. In an 1865 letter to the governor of Louisiana, published after his death, President Lincoln indicated that he would support voting rights for “some of the colored people” in the state, “for instance, the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks.” Even President Johnson privately conceded that literate, property-owning African Americans should be enfranchised. But when the suffrage question arose during the debate over the Civil Rights Act of 1866, its drafters made sure the bill had “nothing to do with the political rights or status of parties.”

The Republicans’ resounding victory in the 1866 midterm election spurred a new willingness to confront the suffrage issue. In the brief legislative session that followed the election, before the new class of lawmakers was seated, emboldened Republicans passed a measure to extend voting rights to African American men living in the District of Columbia. The law took effect in January 1867, after Congress voted to override yet another of President Johnson’s vetoes. That same month, lawmakers introduced Black male suffrage in the United States territories. Then, in February 1867, they admitted Nebraska to the Union “upon the fundamental condition” that its eligible Black residents not be denied the right to vote.

Once the 40th Congress assembled in March 1867, the expanded Republican majority launched its project of Radical Reconstruction in the South. Its first order of business was to supplant the all-white state governments reconstituted from the wreckage of the Confederacy. Three Reconstruction Acts, enacted in 1867 over Johnson’s vetoes, divided the South into temporary military districts administered by army generals and set new terms for the readmission of the former Confederate states. First, the rebel states were required to grant the franchise to “the male citizens of said State, twenty-one years old and upward, of whatever race, color, or previous condition.” Second, they would have to hold conventions to draft new state constitutions guaranteeing universal male suffrage, subject to approval by Congress and the states’ voters in a referendum. And third, as noted earlier, they had to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment.

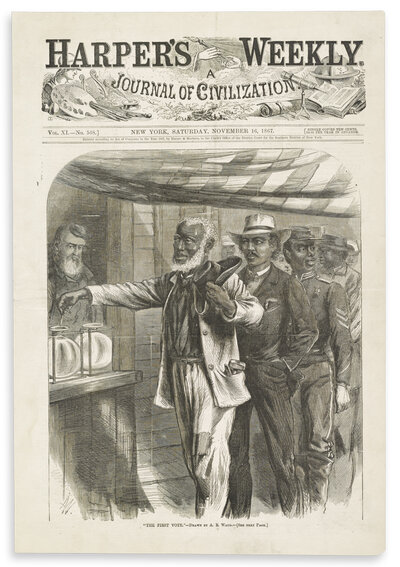

The Reconstruction Acts also laid out procedures for registering voters and organizing state constitutional conventions. Taken together, these measures dramatically expanded the electorate in the ten covered states (Tennessee was exempted). Within a year, more than seven hundred thousand African Americans were added to the voter rolls and, by 1868, they were voting in large numbers throughout the South. In five Southern states—Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina— African Americans made up the majority of the electorate. The Reconstruction Acts resulted in the broadest expansion of the franchise in a generation, since the Jacksonian Era push to expand the electorate to include all white men. One local Tennessee newspaper criticized the new policy for its tendency to “degrade and disgrace our form of government.” The Republican plan, the paper claimed, would “cheapen the right to suffrage, by bestowing it upon ignorant, besotted masses, excluding there from the brightest intelligence and political experience.”

This striking expansion of the franchise in the South stood in stark contrast to what was occurring in the rest of the country. By 1868, only seven states outside of the region permitted Black people to vote. Most of the others had enacted laws decades earlier to exclude Black people from the rolls, even as they moved toward universal suffrage for white men. When voters in eight Northern states considered measures to repeal these race restrictions between 1865 and 1869, the ideal of equal suffrage crashed into a rock of white resistance. Voters in Iowa and Minnesota agreed to liberalize their laws. Elsewhere, though, Northern Democrats rode a wave of backlash, making big gains in the state elections of 1867. A San Francisco newspaper prayed that “the common sense and latent prejudice of the country may be relied upon . . . to preserve us from the monstrous folly of erecting unqualified negro suffrage into a national ‘institution.’ ” The Republican Speaker of the House, Schuyler Colfax, spoke for many in his party when he wondered if the Republicans had gotten “ahead of the people.”

MPI/Stringer

MPI/Stringer

As the presidential election of 1868 loomed, Democrats assailed the Republicans for their “unparalleled oppression and tyranny” in subjecting the South “to military despotism and negro supremacy.” Their party plat- form pledged to return “the privilege and trust of suffrage” to the states. Republicans, on the other hand, attempted to straddle the sectional divide, endorsing the Reconstruction policy of “equal suffrage to all loyal men” in the South while reassuring Northerners that “the question of suffrage in all the loyal states properly belongs to the people of those states.” This two-track approach drew fierce criticism. The New England Anti-Slavery Society denounced the position as “a practical surrender of the whole question.” Sumner called the platform plank “foolish and contemptible,” while Stevens lambasted his “skulking” party for its “cowardly and mean” approach to the question.

The election results shocked the Republicans. The party’s nominee, the former Union general Ulysses S. Grant, won the popular vote by an unexpectedly narrow margin—about three hundred thousand votes out of nearly 6 million cast. During the campaign, Grant barely mentioned Black suffrage, hoping to sidestep a divisive issue. But now Republicans came to see that their interests lay in enfranchising this new and potentially loyal constituency. They recognized too that the former Confederate states would act to suppress the Black vote at the earliest opportunity. With a sense of urgency, Republicans began work on a voting rights amendment. They had to get it done before the start of the next Congress, when Democrats would be returning in force. Over two months of debate, lawmakers put forward more than sixty proposals. One measure offered by a Pennsylvania congressman would have instituted universal suffrage with “no distinction of wealth, intelligence, race, family, or sex.” But for the most part, the proposals focused on male suffrage. The decision led to a rift with woman suffragists who had supported the abolitionist cause.

There was considerable disagreement on what the amendment should say. Should it affirmatively recognize a fundamental right to vote? Or should it merely prohibit discrimination in voting? Should the amendment outlaw only abridgments based on race, color, and previous condition of servitude? Or should it extend more broadly to discrimination based on religion, education, national origin, and property ownership?

Congressman George Boutwell, a Massachusetts Republican, was an early supporter of securing “universal suffrage to all adult male citizens of this country.” Willard Warner, a “carpet-bagging” Ohio Republican representing Alabama in the Senate, concurred, proclaiming “it is the duty of the hour to put into the Constitution a grand affirmative proposition which shall protect every citizen of this Republic in the enjoyment of political power.” Such an amendment would have the virtue of making the right to vote explicit in the Constitution for the first time. But most members of Congress were not ready to embrace such a radical break with the tradition, dating back to the decision of the Framers, of leaving voting rules in the hands of the states. Their “dodge” has been to “our collective peril,” says law professor Lani Guinier, leaving “one of the fundamental elements of democratic citizenship tethered to the whims of local officials,” freeing them “to enact restrictive voting policies that would block millions of citizens from the ballot box.”

Nativism also figured into the lawmakers’ hesitancy. Members of Congress from Pacific Coast states feared the amendment would enfranchise the region’s Chinese American population. “They are a people who do not or will not learn our language,” said a senator from Oregon. “They cannot or will not adopt our manners or customs and modes of life.” Lawmakers from the East had anti-immigrant prejudices of their own. Warning of an influx of Catholics from Europe, Senator James Patterson of New Hampshire asked, “Why should we throw open this portal of political power and let into the strongholds of our Government the emissaries of arbitrary power, the minions of despotism?”

For these reasons, the lawmakers coalesced around a more tightly crafted amendment to prevent discrimination based on race. Massachusetts senator Henry Wilson argued for a broader ban on discrimination “on account of race, color, nativity, property, education, or creed.” But Nevada Senator William Stewart spoke for most when he argued that an amendment addressing race was the “logical” next step. “It is the only measure that will really abolish slavery,” he said. “Let it be made the immutable law of the land; let it be fixed; and then we shall have peace.”

After agreeing to limit the amendment’s protection to African American men, some in Congress wanted the measure to protect the right to hold office as well. Advocates of this approach cited an incident in Georgia, in which the legislature ousted more than two dozen duly elected Black members. Some lawmakers worried that the added provision would complicate the prospects for ratification. Others, like Massachusetts congressman Benjamin Butler, rejected the premise that such a right needed to be spelled out. “The right to elect to office carries with it the inalienable and indissoluble and indefeasible right to be elected to office,” said Butler.

As the session clock ticked down, Democrats raised familiar objections grounded in states’ rights and white supremacy. They were joined by a handful of conservative Republicans. One decried a “revolution . . . striking at the life of republican institutions within the States themselves.” Echoing Willard Saulsbury’s objection to the Thirteenth Amendment, another lawmaker maintained that the proposal exceeded implicit “limitations” on the constitutional amendment power, enabling Congress to undermine “the institutions of the State” to put “their local frames of government, their sovereignty, and their powers altogether within the control of three fourths of the other States.”

Democrats further charged that Republicans only supported the amendment for their own partisan advantage: “to maintain the dominance” of the Republican Party “by means of the degradation of the suffrage” as one lawmaker put it. At the same time, they looked for ways to put this controversial question before the people in state ratifying conventions. Charles Sumner chastised the Democrats for their demagoguery, likening them to “the witches in Macbeth”—presiding over “a political caldron, into which will be dropped all the poisoned ingredients of prejudice and hate,” wielding the amendment as “the pudding-stick with which to stir the bubbling mass.”

In the session’s final days, the choice came down to two competing measures. The Senate passed a narrowly drafted amendment to ensure that the right to vote and hold office could not be denied or abridged on the grounds of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The language approved by the House would protect more broadly against discrimination based on “race, color, nativity, property, creed, or previous condition of servitude.” It was left to a conference committee to reconcile the differences. What emerged is the language of the Fifteenth Amendment we know today: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” While drafts from both houses included protections for the right to hold office, that provision was mysteriously dropped in the final measure.

The redraft frustrated many members. But with adjournment approaching, there was little time left to make further changes. On February 25, 1869, the House adopted the conference committee’s measure by a vote of 144–44. The next day, senators who had hoped for more offered their reluctant support. “I am prepared to believe that we must accept the report of this committee or abandon all hope of any amendment of the Constitution being proposed by this Congress,” said Vermont’s Justin Morrill, reflecting the view of many Republicans. It was, he conceded, the “best that we can obtain.” Senators approved the measure on February 26 by a vote of 39–13. Charles Sumner cast a principled vote of “absent,” complaining that the amendment did not go far enough. Willard Warner called it “unworthy of the grand opportunity that is presented to us.” He predicted that his adoptive home state of Alabama would disenfranchise 90 percent of the Black electorate through the use of literacy tests and property requirements not specifically based on race.

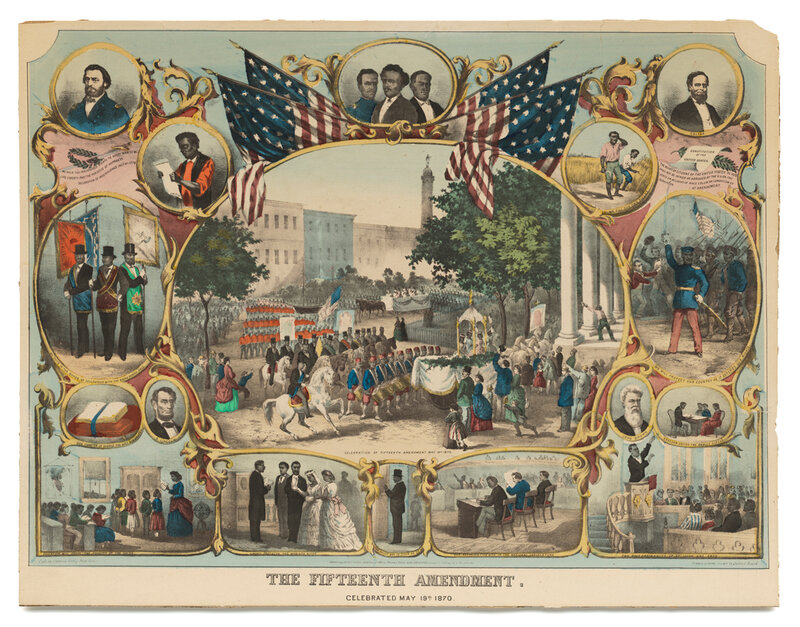

Heritage Images/Getty

Heritage Images/Getty

Despite the controversy, the Fifteenth Amendment achieved ratification in less than a year. A February 3, 1870, vote by Iowa’s legislature put the measure over the top. The border states of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Tennessee rejected the measure, as did the Pacific Coast states of California and Oregon, where anti-Chinese sentiment was strong. In the end, the amendment’s adoption depended on the vote of four Southern states still under military rule. Virginia, Mississippi, Georgia, and Texas all voted to ratify the amendment as a condition to having their statehood restored. Without them, the amendment would not have obtained the support of the twenty-eight legislatures needed for ratification. The measure’s adoption was clouded by another controversy over rescission. In January 1870, New York’s legislature sought to revoke its ratification following an election giving control to the Democrats. Once again, when Congress certified the amendment, it refused to recognize the action, including New York in the list of ratifying states.

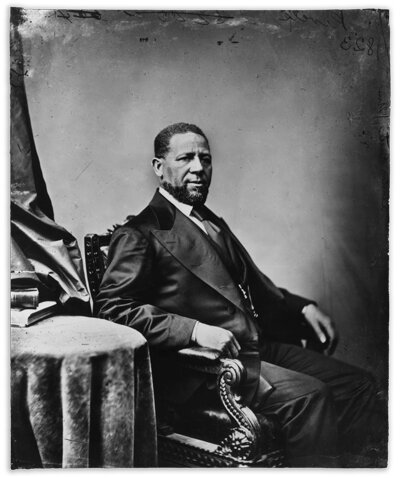

On April 11, 1870, two months after the amendment’s adoption, Mississippi senator Hiram Revels, the first African American to serve in Congress, delivered an address to mark the joyous occasion.

The final result of our triumph, the cap-stone of the temple of Liberty, the crowning glory of the edifice raised to Freedom, was the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, which we now celebrate. This sacred Amendment, now welded in and become part and parcel of our glorious Constitution—bone of its bone, flesh of its flesh— which strikes down the last hope of the rebellion; which abolishes, so far as statutes can abolish, the last civil and political distinction between different classes of our citizens, uniting the entire nation into one harmonious whole. “E pluribus Unum” is the glory of the hour. This Amendment, which firmly places the ballot in the hands of the male adult members of a race numbering from four to five millions, had become a political necessity as imperious as was the military necessity which placed the bayonet in the same loyal hands.

Civil rights leaders also reveled in the amendment’s ratification. The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society proclaimed: “Beneath that broad banner of civil and political liberty, the white man and black man stand, side by side.” William Lloyd Garrison celebrated “this wonderful, quiet, sudden transformation of four millions of human beings from the auction block to the ballot-box.” Over the protest of some of its members, the leaders of the American Anti-Slavery Society, the organization Garrison founded, declared that “the work for which the society had been organized was complete.”

MPI/Stringer

MPI/Stringer

Since its adoption, scholars have debated the motives behind the last- minute push to add a third Reconstruction Amendment. Some believe that the Republicans were, first and foremost, concerned with their own political power. According to this view, adopting the Fifteenth Amendment was aimed primarily at bringing Black voters into the party fold—“a conversion of expediency rather than one of conviction.” Others see Radical Reconstruction as “the last great crusade of the nineteenth-century romantic reformers.” In this analysis, the moral imperative that drove the abolitionist cause also motivated the lawmakers’ determination to secure African American citizenship and political rights.

Ultimately, even principled politicians are politicians. Charles Sumner, the great abolitionist champion, was well aware that the enfranchisement of African Americans would be a boon to the Republican Party. “Wherever you most need them, there they are,” he said, “and be assured they will all vote for those who stand by them in the assertion of equal rights.” But the claim that the party got behind Black suffrage out of calculating self-interest obscures some essential history. Lawmakers who supported the Fifteenth Amendment were, for the most part, principled supporters of rights for African Americans who demonstrated this commitment by consistent votes on issues affecting the Black population. Given the pervasiveness of racism in the country, Republicans took these positions at great political risk. In the North, where the party was strongest, there were relatively few African Americans to swing elections. Moreover, in states where the suffrage question was put before voters, the party paid a political price.

In the end, the party of Lincoln was hardly “radical” when it came to voting rights. Republicans pressed for the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment while they still held a supermajority in Congress to advance it. Even so, despite constant prodding by idealists, the party coalesced around a conservative solution. Hesitant to disrupt a core feature of the original Constitution, the drafters of the Fifteenth Amendment left states in charge of their own voting rules, with consequences that reverberate to this day.

For decades, segregationists and their enablers sought to discredit the “so-called Fifteenth Amendment,” insisting that it was adopted under “duress.” It is clear that the South’s recalcitrance justified the Radical Republicans’ exercise in “constitutional hardball.” The question is, was the product of all that effort enough? The recent proliferation of vote- suppression measures in the states—from voter ID laws to the suspicious purges of voter rolls, all sanctioned by the courts—suggests the answer is no.

© 2021 John F. Kowal and Wilfred U. Codrington III. This excerpt originally appeared in The People’s Constitution: 200 Years, 27 Amendments, and the Promise of a More Perfect Union, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.