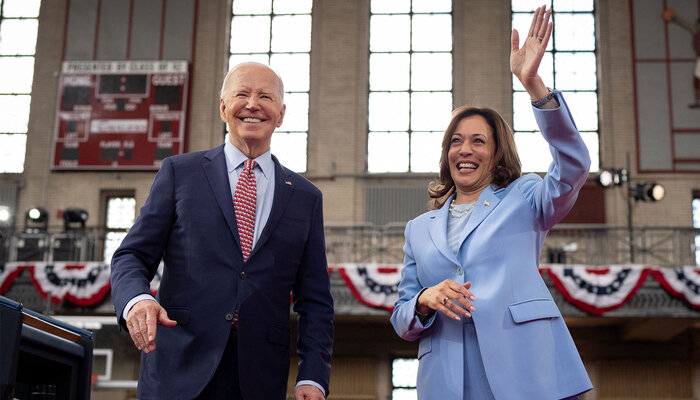

President Biden’s decision to bow out of the 2024 presidential race has raised a pressing question now that he is likely to be replaced at the top of the ticket by Vice President Kamala Harris: What will become of the Biden-Harris campaign’s substantial campaign war chest, which stood at some $240 million as of the day he left the race?

A significant portion of that $240 million is already under the control of the Democratic National Committee and other party committees and thus is entirely unaffected by Biden’s withdrawal. But more than $90 million was held by Biden’s principal campaign committee — the official vehicle for the Biden-Harris reelection campaign. FEC filings suggest that those funds will now be used by the Harris campaign. Is that legal?

Most campaign finance experts think it is. The rationale here is straightforward. FEC regulations provide that “any campaign depository designated by the principal campaign committee of a political party’s candidate for President shall be the campaign depository for that political party’s candidate for the office of Vice President.” Therefore, Biden’s committee, which was also his principal campaign committee in 2020, has jointly listed Harris in its FEC filings ever since she first became his running mate. Once Biden withdrew from the race this year, the committee simply updated its FEC registration to replace Biden with Harris at the top of the ticket.

It is true that FEC regulations and federal statutory law do not address this exact situation — an incumbent vice president running for reelection and then moving to the top of the ticket before having been formally renominated at her party’s convention. But the commission has never suggested that an incumbent vice president must at any point establish her own campaign committee, let alone provided specific guidance for when doing so might be necessary. All incumbent presidential and vice-presidential candidates in recent memory have run for reelection together as a single ticket, sharing one committee before and after formal renomination. The Harris campaign is understandably relying on this precedent.

It is not even clear that this approach offers the campaign a significant financial advantage. Running together as one ticket means that the president and vice president are subject to a single set of contribution limits. If a donor already gave the legal limit to the Biden-Harris campaign (as many wealthy donors have), the Harris campaign cannot go back and solicit more money from them. If Harris’s campaign were instead considered separate from Biden’s, it would be free to ask these donors for more money.

In the meantime, the campaign would not necessarily have to return the original Biden-Harris war chest; all or at least part of it could just be redirected to the DNC, which is allowed to accept unlimited transfers from candidates. The money could then still be used to support the new ticket. The effect, as another commentator has noted, would essentially be to double the legal contribution limits for presidential campaigns, injecting even more money into the process.

Nevertheless, former President Trump, the conservative group Citizens United (plaintiff in the notorious Supreme Court ruling that led to the evisceration of many other campaign finance rules), and a number of Republican state parties have all filed complaints with the FEC. They argue that Harris cannot access the Biden-Harris funds and that — as the Trump complaint puts it — the campaign’s attempt to use them amounts to a “heist.”

Overblown rhetoric aside, there is certainly some room for legal argument here. Given the FEC’s history of allowing joint campaign accounts between incumbent presidential and vice-presidential candidates, however, these complaints are unlikely to gain traction. Even if the law ultimately does not favor the Harris campaign’s position, FEC commissioners have in the past cited unclear rules as grounds to dismiss complaints as a matter of prosecutorial discretion, and there would certainly be a compelling case for such a dismissal here. For better or worse, that decision would be unreviewable in court under current law.

In any event, the evenly divided FEC’s sluggish track record in resolving disputes — often taking years — makes it highly unlikely the commission will rule on this issue before the election. And given the record pace at which the Harris campaign is raising new money, the question of whether they are ultimately entitled to the remaining Biden-Harris campaign funds may be largely academic.

There is no small amount of irony in the fact that some of the loudest voices crying foul in this matter are those who have been at the forefront of successful efforts to weaken the very rules they accuse the Harris campaign of breaking. Thanks to these efforts, campaigns already have effective ways to sidestep most legal limits on their fundraising. For instance, candidates can establish and work closely with supposedly independent super PACs, which are free to raise unlimited money from billionaire megadonors (even donors who own companies doing business with the government). Campaigns can also rely on outside “dark money” groups that keep their donors secret, whose spending is increasing and becoming even harder to track. And no matter how far any of these actors push the legal envelope, they usually have little to fear from the FEC, which often struggles to enforce the law even when it is clear.

In short, there are real and enduring problems with our campaign finance system that a substantial majority of Americans across the partisan spectrum want elected leaders to solve. The presumptive Democratic nominee’s use of funds raised jointly with her predecessor in accordance with legal limits to benefit her party’s ticket is not one of them.