This is an excerpt from the new edition of The Fight to Vote by Brennan Center for Justice President Michael Waldman. The book tells the dramatic story of the continuous struggle to win and maintain voting rights throughout American history, with two new chapters recounting the new assault on voting rights and the push for federal legislation to stop it.

On March 26, 2021, Georgia governor Brian Kemp sat at a polished table, brow furrowed, pen in hand. Six middle-aged white men in dark suits flanked him. They posed in front of an oil painting of a slave plantation. Kemp was there to sign the Election Integrity Act, a statute born in controversy, targeting Black, Latino, and Asian voters, which would help set off a high-decibel national debate. As the men stood stiffly, Representative Park Cannon, a Black Democratic legislator, knocked on the door of the governor’s office. Two beefy state troopers grabbed her by both arms and arrested her, dragging her through the halls and out of the Capitol.

In a lurid flash the tableau captured a dramatic political story. In the early months of 2021, the Big Lie drove state legislatures across the country to mount an attack on voting rights—the most concerted attempt to roll back voting since the Jim Crow era.

Alyssa Pointer/Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP

Alyssa Pointer/Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP

By the Brennan Center’s ongoing count, Republican legislators introduced more than four hundred bills in forty-eight states to restrict the vote. These were not just thrown in the hopper by backbenchers hoping for a few good hours on Twitter. By October 2021, thirty-three bills in nineteen states had become law. Many of these proposals aimed to undo the practices that had successfully expanded access the previous year—especially those that let citizens vote by mail or early. Others expanded purges (which removed people from the rolls) or authorized partisans to harass citizens. The push came hardest in states with the fastest-growing minority populations, states that had flipped to the Democrats or were threatening to do so. And the proposed restrictions uncannily hit hardest Black, Latino, and Asian citizens. Many of these measures once would have been stopped or slowed by the Voting Rights Act and its requirement that such changes be “precleared” by the Justice Department or a federal court. Now, thanks to the Supreme Court, legislators could act with impunity.

The fight first came into view in Georgia. Vote by mail had been enacted there by Republicans, but in 2020 it was heavily used by Democrats. The legislature prepared to effectively repeal it for those under sixty-five—meaning that older, whiter, more conservative citizens could still vote absentee. The proposal ended early voting on the Sunday before Election Day, the day Black churches organized “souls to the polls” drives. It repealed automatic voter registration, which Brian Kemp had proudly created as secretary of state just a few years before.

For some Republicans, it went too far. The state’s lieutenant governor refused to preside over the legislative debate. Lobbyists for major corporations including Delta Air Lines and Coca Cola—long allies of the Georgia Republican party—urged a retreat. The behind-the-scenes scramble had some impact. As finally passed, the restrictions were less severe—but they were just as targeted. The new law banned mobile voting centers, for example, which only had been used in Atlanta. It made it a crime to give water or snacks to people waiting in line at a polling place, in a state where Black people were far more likely than white people to have to queue for long periods. It cut back on drop boxes and required more proof of identity to vote absentee.

At the last minute, sponsors slipped in perhaps the most dangerous provision. It sought to undermine the independent officials who had stood up to Trump and declared Biden the victor. The law created a new election board responsible to the Republican legislature, taking power away from the secretary of state. The law also effectively let the legislature remove county election officials (raising the risk that state lawmakers could simply take over the machinery in Democratic Atlanta). It was a new ominous twist: aiming not only to limit who could vote but rig who could count the votes. Not just vote suppression, but election subversion.

Georgia’s law had a concussive impact. President Biden denounced it as “Jim Crow in the Twenty-First Century.” Corporations that had professed fealty to racial equality the year before during Black Lives Matter protests now felt pressure from their own employees to do something. Executives, led by Ken Frazier, the CEO of Merck, and Ken Chenault, former CEO of American Express, signed protests and took out full-page ads. Major League Baseball moved the All-Star game out of Atlanta. The Georgia House, in turn, voted to revoke a jet fuel tax break that benefitted Delta Air Lines in punishment for its criticism of the new law. Senator Mitch McConnell, long the champion of Citizens United, now warned corporations to “stay out of politics.”

Voting restrictions moved forward in other states. The governors of Iowa and Florida signed new laws. Ugly motives were barely concealed. An Arizona legislator who sponsored that state’s proposals made headlines when he said that he did not think everyone should vote. At a hearing on a restrictive bill, Representative John Kavanaugh explained that when it came to voters, “Quantity is important but we have to look at quality as well.” Texas bill S.B. No. 7 originally said it aimed to protect the “purity of the ballot box,” a phrase from the state’s constitution used to justify all-white primaries in the Jim Crow era. The wording was removed only after it was called out during a contentious debate on the bill.

Increasingly it became clear that a key strategic goal was to remold state election machinery to hand control to partisans. New laws and proposals targeted who would count the votes, stripping power from election officials. These schemes aimed to ensure that in 2024, independent officials could not stand up to political bullying as they had in 2020.

In Texas, legislation neared passage in June 2021 that would cut back on early voting, and impose criminal penalties on local officials who widely send out ballot applications. It barred drive-through voting and twenty-four-hour polling places, the innovations implemented by Lina Hidalgo in Harris County in 2020. It prohibited voting on Sunday mornings, the time used by Black churches for “souls to the polls” organizing drives. And it gave partisan judges the power to overturn election results. Following the trend set by Georgia, it imposed vague new criminal penalties on election officials if they modified or suspended rules in an emergency unless it is “expressly authorized” by the state’s election code. “Other portions of S.B. No. 7 impose criminal penalties for activities involving counting ballots, dealing with mail-in ballot applications, mailing early voting material, provisional ballots, ballot duplication, and poll watchers,” a watchdog group summarized.

With an hour left to go, Democratic lawmakers bolted, leaving the Senate short of a quorum and temporarily killing the bill. The governor called a special session in July to focus on restrictive election laws. When it began, Democrats slipped out of Austin, chartered a plane, and flew out of state. Texas governor Greg Abbott threatened to arrest them. Eventually they would trickle back to Texas, and the legislation eventually passed, but not before the lawmakers made a point on the national stage.

“We are now taking the fight to our nation’s Capitol,” the Democrats said in a statement. “We are living on borrowed time in Texas.” They resurfaced in Washington, D.C., where they joined a movement demanding federal action.

For the People

It had the makings of an epic clash: state legislatures were rushing to restrict the vote. At the same time, Congress had the power to stop that voter suppression in its tracks—legally and constitutionally. The great question was whether it had the political will to do so.

Already, for the first time in decades, Democrats and progressives had begun to put democracy reform at the center of their politics. The new focus took shape after the 2016 election. Trump’s victory startled many Americans, shaken by the country’s divisions and the rise of angry white nationalism as a mainstream political force. Many saw Trump as part of a global backlash against pluralist, multiracial democracy.

In Grand Rapids the morning after Trump won, a twenty-eight-year-old named Katie Fahey sat in her kitchen and scrolled, wincing, through her social media feed. She tapped out a Facebook post. “I’d like to take on gerrymandering in Michigan,” she wrote. “If you’re interested in doing this as well please let me know.” She added a smiley face emoji. Within weeks thousands of volunteers had signed up, and drafted a ballot measure to set up a nonpartisan commission to conduct redistricting. Relying only on volunteers, Fahey’s group gathered signatures in the snow to qualify the proposal for the ballot. It won, as did similar laws in Colorado, Missouri, and Utah. That same day, in Florida, voters ended that state’s notorious felony disenfranchisement system, which had barred 1.4 million from voting. A ballot measure to restore the right to vote for people with a past felony conviction needed 60 percent to win. Organizers, many of them formerly incarcerated, enlisted conservatives, religious leaders, and police chiefs. Instead of hiding they went door to door, asking to have their rights restored. Amendment Four passed with a surprising 64 percent. Republican legislators quickly moved to undo the change, and civil rights groups were challenging that in court.

Associated Press

Associated Press

Politicians responded to the surge in public support for reform. Sixteen states plus the District of Columbia had passed or implemented automatic registration, boosting rates across the country. Most were Democratic-leaning states, but not all. Alaska voters enacted it by ballot measure. In Illinois, Republican governor Bruce Rauner signed it into law after legislators passed it unanimously.

In 2017, Democrats took control of the U.S. House of Representatives. Nancy Pelosi returned as Speaker. It was far from obvious that party leaders would embrace reform. (Representative Steny Hoyer, Pelosi’s deputy and longtime rival, had told me previously, “If we win, let me tell you what we’re going to focus on: not this. People don’t care.”) Why the shift? A new political action committee, End Citizens United, had mobilized Democratic candidates who announced they would shun corporate funds. The group was explicitly political. Forty new lawmakers were elected with a pledge to make political reform a top priority. Pelosi introduced the For the People Act with the symbolically significant denominator H.R.1.

It was novel to find democracy reform at the center of either party’s agenda, and some lawmakers were uneasy. A cluster of Democratic House members quietly resisted. On a street near the Capitol one morning, a congressman told me he would oppose the plan, and that few cared. His timing was off. At that very moment, a block away, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the newly elected firebrand from New York City, challenged a panel of witnesses, “Let’s play a game.” Methodically she drew them out to show how porous campaign finance and ethics laws were. A video of the exchange went viral, quickly amassing 40 million views, making it the most watched political video ever on Twitter, all on the arcane topic of election and lobbying law. The caucus quickly fell in line, and H.R.1 passed the House on March 8, 2019. It was the most sweeping democracy reform plan to pass either chamber of Congress in half a century.

Now it was January 2021, and somewhat to their surprise after the ups and downs of the election season, the Democrats had control of the White House, House, and Senate. (With a fifty-fifty split, the vice president breaks Senate ties to give the party the control.) And with states rushing to pass restrictive laws, federal voting rights legislation suddenly seemed not like a “nice to do” item or a “want to do” but a “must do.”

The For the People Act would set national election standards, guaranteeing access to vote by mail and requiring adequate early voting. It would extend automatic voter registration nationwide. It also addressed redistricting: establishing guidelines to block racial and partisan gerrymandering, and setting up independent commissions to draw lines. The bill included significant campaign finance reform. It would require disclosure of “dark money,” the funds used in elections that were not disclosed. It also would revive the federal system of public financing of campaigns, with matching funds provided for small individual contributions to congressional or presidential candidates.

The voting and redistricting provisions, in particular, would override the actions of state governments. Congress has the power to do this under the Constitution’s Elections Clause. (That’s the provision James Madison insisted on, using “words of great latitude” because it was “impossible to foresee the abuses” legislatures might dream up, described in Chapter 2.) The Supreme Court recently reaffirmed that sweeping authority. In a 2019 ruling, an opinion written by Chief Justice Roberts noted, “the Framers gave Congress the power to do something about partisan gerrymandering in the Elections Clause,” and even pointed to H.R.1 as a prime example.

Bill Clark/Getty

Bill Clark/Getty

A second piece of important legislation moved along a parallel track. It aimed to restore the full strength of the Voting Rights Act after it was gutted by the Supreme Court. It would reestablish “preclearance,” which had been the law’s most effective element. The legislation was renamed the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. To overcome the justices’ skepticism about whether the Voting Rights Act could be constitutional at all, sponsors painstakingly amassed data and evidence of continued racial discrimination. The measure would not pass the House until August 2021.

Biden had not campaigned on avid support of voting legislation. But like many, he was shaken by the election and Trump’s effort to overturn it. He had sponsored earlier laws to reauthorize the Voting Rights Act. His true passion as a young legislator was campaign reform. In the spring of 1993, he paid an off-the-record visit to President Bill Clinton in the Oval Office. Democrats were drafting campaign finance reform, and I attended as Clinton’s aide working on the legislation. Go further, Biden urged. Try to enact full public financing of campaigns. It would change Washington. Biden’s voluble passion was striking, his idealistic language not often heard in the Oval Office. The bill Democrats proposed that year was far weaker than Biden hoped for, and it failed in any event. At the time Biden had little organizational backing for his stance.

Now an energized grassroots movement pressed for action. For decades, democracy reform failed to reach the top tier of progressive goals partly because of divisions between civil rights groups, led by people of color, and good government groups, principally white and suburban. That was especially true on issues including redistricting reform and campaign finance. Not this time: melding voting rights with anti-corruption proposals turned out to be a force magnifier. Now explicitly political committees, including a group led by former Attorney General Eric Holder that pressed for redistricting reform, and Stacey Abrams’s Fair Fight Action, played prominent roles. Progressive grassroots networks including Indivisible and MoveOn joined insurgent groups that arose in the racial justice movement, such as Black Voters Matter. Traditional reform lobbies Public Citizen and Common Cause had their own coalition. Labor unions, once skeptical of reform, mobilized members. It was the broadest push in decades. Fretful commentators who thought a trimmed-down bill might find an easier path to passage misread the political strategy: narrower bills have narrower constituencies of support.

Once again H.R.1 passed the House. Now it was also introduced as the lead bill in the Senate: S.1. Majority Leader Charles Schumer repeatedly declared, “failure is not an option.” The legislation was wildly popular. A tape of a private briefing held by the conservative Koch network, leaked to Jane Mayer of the New Yorker, suggests its potency. The group’s pollster had tested arguments against the measure, and found, disconcertingly, that Republicans as well as independents and Democrats strongly supported the bill. Better not to try to argue against it, he explained, since turning public opinion would be “incredibly difficult.” Better to rely on, instead, “under-the-dome-type strategies” to obstruct the bill. As Senator Ted Cruz of Texas told lobbyists in his own leaked phone call, this was “an all-hands moment.”

Indeed, the legislation would soon crash hard into the arcane rules of the U.S. Senate. It takes sixty senators to end a filibuster, and thus allow a vote on legislation. The filibuster is not in the Constitution. In fact, the framers considered and rejected the idea of requiring supermajorities. It was used throughout the twentieth century especially to thwart civil rights legislation. Then, as parties grew more polarized, it became used to block . . . well, almost anything. It is simply assumed that legislation require sixty votes. In 2013, for example, after the massacre of elementary school children at Sandy Hook, legislation to strengthen background checks for gun purchases had 90 percent public support and a majority of the Senate. It died due to a filibuster. Senate officials tallied as many “cloture” motions to end a filibuster in the past decade as in the entire previous half century.

Now, as in earlier eras, the filibuster was being used to block vital voting rights legislation.

Associated Press

Associated Press

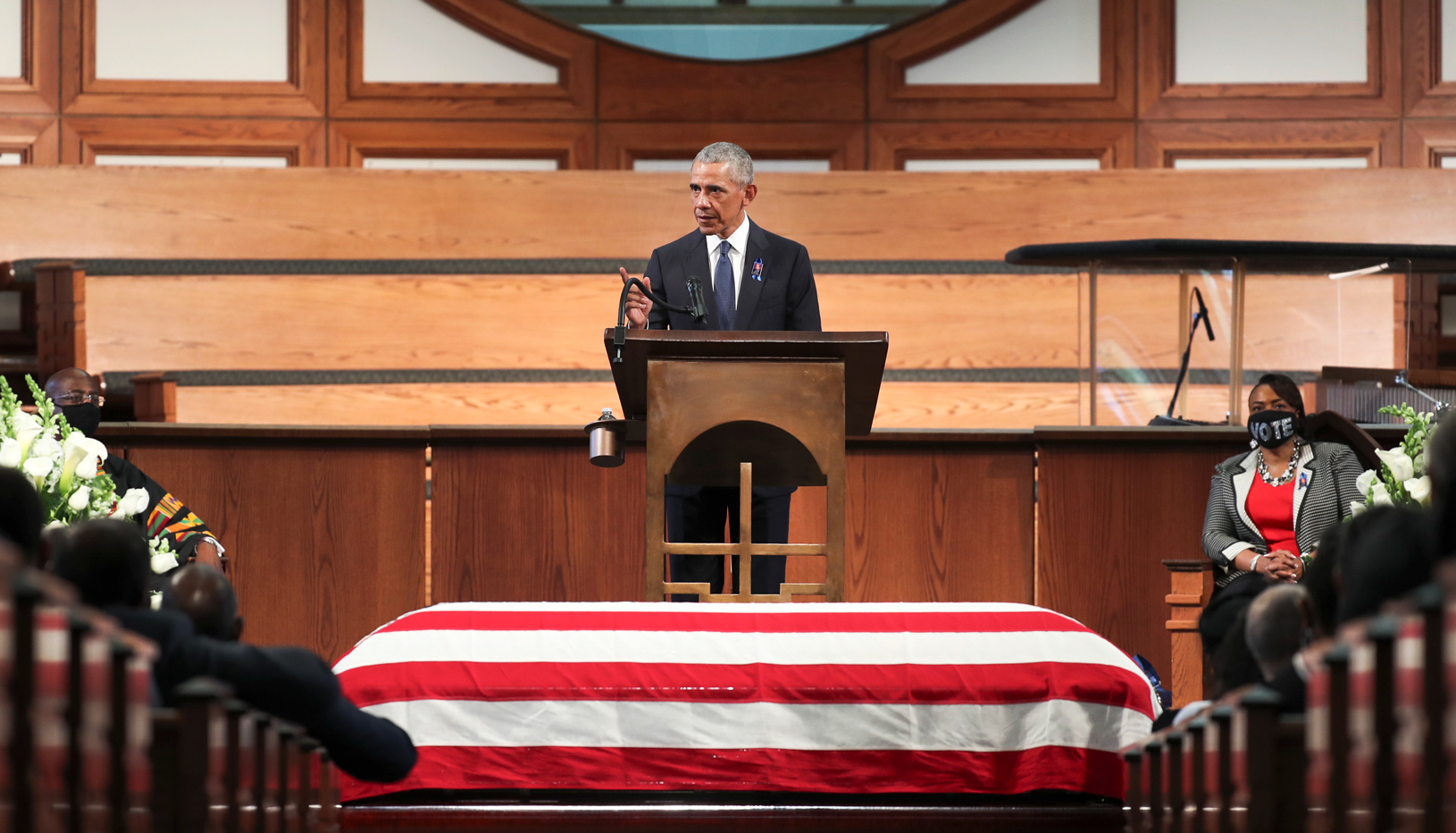

In 2020, Representative John Lewis died. Lewis, of course, had led the march on Edmund Pettus Bridge that led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Since 1987, he had served in Congress, where he was a revered figure. At Lewis’s nationally televised funeral, Barack Obama stood over the late Congressman’s casket. The former president demanded action on voting rights, not in 1965, but now: “Let’s honor him by revitalizing the law that he was willing to die for.” Obama called for passage of the For the People Act. “And if all this takes eliminating the filibuster—another Jim Crow relic—in order to secure the God-given rights of every American, then that’s what we should do.” Obama’s pungent words stung. As president he had done little to advance the issue. Now he had crystalized a new growing consensus among Democrats: the filibuster must go.

Senators had changed the filibuster before. In 1974, they cut the number of votes needed to end a filibuster from sixty-seven to sixty. In the past decade, Republicans and Democrats had ended it for Supreme Court, lower court, and executive branch nominations. Exceptions already were carved out for bills ranging from budget reconciliation to military base closings and trade agreements, all of which required only a majority.

In 2021, two Democratic senators, Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, made clear they did not want to eliminate the filibuster. Manchin’s stance perplexed. He was a former secretary of state who had sponsored the predecessor reform bill in years past, but now insisted on Republican support—an impossibility in the polarized Congress. He declared he would not back S.1. Then he proposed the elements of a stripped-down version of the bill that—while less sweeping—still included key voting, redistricting, and campaign finance rules. When Senator Schumer tried to begin debate on June 22, fifty Republicans objected, stopping the bill, at least for now. Later in the summer they blocked votes on redistricting and “dark money” campaign spending. In September, Manchin and other Democrats formally introduced the new version of the legislation, now rechristened the Freedom to Vote Act. Even in its new form, it would be the most significant voting right bill in decades.

Will there be enough political pressure and momentum to force action, including the possibility of a carve-out to the filibuster for election laws? Will the Freedom to Vote Act simply die in the Senate, a victim of the crowded congressional calendar? Will Joe Biden throw the full weight of the White House behind the urgent need for reform?

Associated Press

Associated Press

In early summer, Biden spoke at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia. He had hastily scheduled the speech after Black leaders challenged him to do more in a White House meeting. The president strode into the atrium of the museum where he had once served as board chair and in simpler times could regularly be found in the lobby, schmoozing and having coffee. Ringed by flags, Biden decried the Big Lie. He urged action on H.R.1, winning thunderous applause, and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. He noted that the Justice Department had doubled the number of lawyers working to protect voting rights. He was particularly incensed by the new provisions finding their way into state laws that gave partisans the power to declare the winner. “To me, this is simple,” he said. “This is election subversion—who gets to count whether or not your vote counted at all.” Rhetorically Biden raised the stakes sky high. “I’ve said it before: We are facing the most significant test of our democracy since the Civil War. That’s not hyperbole. Since the Civil War. The Confederates back then never breached the Capitol as insurrectionists did on January the sixth.” Rhetorically Biden drew a red line. Would such powerful words produce action?

Shortly before Biden walked out to speak, amplifiers blared a soundtrack of classic rock. On came “We Won’t Get Fooled Again,” the 1971 song by The Who about dashed revolutionary hopes. (Meet the new boss / Same as the old boss.) Reformers hoped that was not an omen.

FIGHT TO VOTE by Michael Waldman. Copyright © 2016 by Michael Waldman. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.