The 2024 election was much safer than feared. But threats of violence were also far greater than many realize.

The Brennan Center has confirmed that at least 227 bomb threats targeted polling locations, election offices, and tabulation centers around the country on Election Day and the days after. In addition, we saw explosive devices detonating on ballot drop boxes across multiple states in the Pacific Northwest, hoax calls claiming active shooters at schools serving as polling sites in the Northeast, and law enforcement deploying to voting locations across America in response.

Despite these incidents — seemingly far greater than in the recent past — the media generally described the election as “smooth,” and “almost boring.” Why? Because officials’ preparation meant disruption was minimal. To keep our elections safe and secure in the future, law enforcement and election officials must continue to invest in and build on the joint election security efforts that proved successful in 2024.

The collaboration between election officials and law enforcement ahead of the 2024 election was key to effectual and transparent responses to a variety of crises across the country. This pre-2024 collaboration “was markedly different than the collaboration in prior election cycles, which was often limited to election administrators sharing polling location addresses with local law enforcement,” said Edgardo Cortés, former Virginia Department of Elections Commissioner and current Brennan Center adviser.

Unfortunately, elections are likely to remain a high-profile target. And, as we learned in 2024, threats will continue to evolve and emerge throughout the cycle.

After the 2020 election, election officials faced a spike in threats, with mobs, armed protesters, and other events outside election offices and tabulation centers. While some administrators — such as Orange County registrar Neal Kelley of California and Scott County auditor Roxanne Moritz of Iowa — felt supported by local law enforcement, including sheriffs Don Barnes and Tim Lane, respectively, many did not. As explained by retired Michigan State Police Captain Harold Love, “Law enforcement’s response to these threats was uneven across the country.”

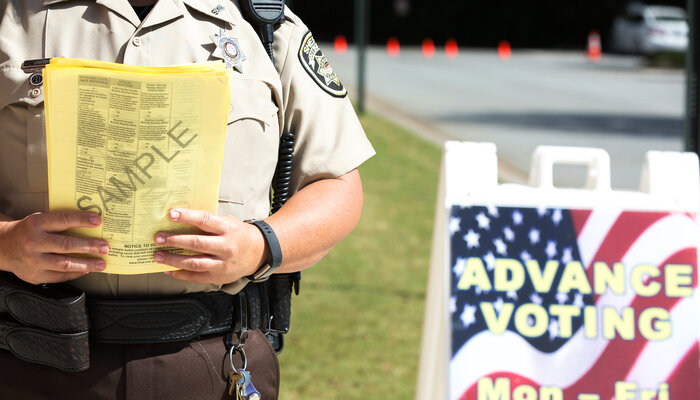

This is unsurprising, as law enforcement faces many challenges in this space. First, there are reasonable concerns about voter intimidation, election interference, and public perception when law enforcement is involved with election security. As explained by Kelley, a former chair of the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections, in congressional testimony, “I believe there are ways to address these growing threats while remaining steadfast in our resolve to recognize that the mere presence of law enforcement in the polls can be viewed as intimidation.”

Additional challenges include state-by-state variations in laws that determine the role of law enforcement in keeping election officials, election infrastructure, and voters safe. Massachusetts, for example, requires a police officer to be present in polling locations, while South Carolina law prohibits law enforcement from entering a polling location “unless summoned into it by a majority of the [polling location] managers.” Further, law enforcement typically receives little or no election-specific training.

Fortunately, leaders in both the law enforcement and elections communities stepped up after the 2020 election. One of the first efforts was a meeting led by Weber County Sheriff Ryan Arbon and County Clerk/Auditor Ricky Hatch between law enforcement and election officials from across northern Utah. It focused on “unit[ing] leaders around a consensus on security needs” and received praise and quick amplification from the elections community. An opinion piece by bipartisan sheriffs, which was highlighted on Face the Nation, affirmed, “Ensuring elections are free from violence, threats and intimidation is a nonpartisan issue. . . . It is critical for law enforcement leaders and election officials to work together.” In Arizona, Maricopa County Sheriff Paul Penzone strategically deployed law enforcement to deter bad actors and clearly communicated intolerance for election-related violence or intimidation in multiple public appearances.

This work paved the way for law enforcement across the country to invest time and resources — in partnership with election officials — necessary for an “all hazards” approach in preparing for the 2024 election, a strategy described by an emergency response firm as emphasizing “preparedness for a wide range of emergencies and disasters, regardless of their cause or nature.” This approach also calls for partnering with a diverse group of stakeholders, including “community organizations to reach vulnerable populations, provide support services, and promote public awareness.”

Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger supported partnering with law enforcement for election security purposes, hosting regional tabletop exercises to bring together police and election officials to practice coordinated responses to a wide range of simulated crises, including bomb threats. Georgia’s Clayton County elections director Shauna Dozier recently spoke about the importance of these exercises after her jurisdiction faced multiple bomb threats on Election Day. (Unlike some other jurisdictions, Clayton County did not close any specific polling locations.) “It was very eye-opening for us,” she said, adding that the training was critical since they had to implement it on Election Day. Law enforcement and election officials conducted similar exercises in dozens of states across the country, including Arizona, California, and Michigan, all of which also faced bomb threats.

Throughout the cycle, when election officials faced threats, they coordinated with their law enforcement and election official colleagues across the country to identify solutions and help others prepare. This sort of interstate collaboration in response to physical threats “at minimum, was not routine, and more realistically, simply didn’t happen before the 2024 cycle,” explained Dane County Clerk Scott McDonell of Wisconsin. For example, in 2023, after election officials in Washington State received mail that contained a suspicious substance, they alerted law enforcement, including the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and other colleagues outside the state. Subsequently, tabletop exercises across the country included a suspicious package scenario, which ensured local officials identified and worked with the local agency responsible for hazardous materials to develop a response plan.

And after multiple election officials became victims of “swatting” — hoax calls designed to initiate a large police presence — law enforcement worked with election officials to share lessons learned. Joint recommendations for swatting mitigations include gathering the home addresses of election officials, election offices, and tabulation centers, and flagging them in the computer-assisted-dispatch system (CADS) to automatically alert 911 staff and responding officers.

Major County Sheriffs of America, National Sheriffs Association, and Major City Chiefs Association, promoted diverse election security planning efforts, stating, “The associations have been in preparation for [the 2024] election for over a year and a half. Our members have participated in tabletop exercises, received briefings from federal, state, and local partners, shared intelligence and threat information, held conversations with election officials, elected officials, and election volunteers, and coordinated with advocacy groups working to secure the election process.”

In mid-2024, the Georgia Peace Officers Standards and Training Council became the first in the country to require election law training for new police officers, including “protections against voter intimidation, election interference and threats.”

These efforts are the foundation of the effective responses to the threats and attacks on the election and were critical to minimizing voter security concerns. This ensured that election outcomes — not election administration — were the big story of the 2024 election.

Election officials and at least one governor were quick to praise law enforcement for their work. Congratulations are certainly in order, but the work is not done. Election security, like cybersecurity, is a race without an end. While both communities made important strides ahead of the 2024 election, without ongoing investment these gains may be quickly lost.

In addition, there may be more transferable lessons from other law enforcement planning resources. For example, Florida’s Hillsborough County Supervisor of Elections Craig Latimer who is a former major with the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office noted, “We can learn a lot from how other major events — such as a Super Bowl — are handled.” It is worth exploring whether some “major events” mitigation tactics, such as pre-event bomb-sniffing dog sweeps, are feasible for elections.

Looking ahead, bomb threats, swatting, and other threats will likely continue to target our elections. Election officials and law enforcement must remain prepared for it all. Innovative information sharing partnerships, such as the joint efforts piloted by national law enforcement associations or Washington State and the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center, are just two examples of the steps that officials can take to strengthen the infrastructure critical to keep elections safe.

Requiring or at least offering election law training for officers is another option. To ensure that elections remain “boring,” state and local officials must continue to invest in proven coordinated election security planning efforts and innovate as new threats emerge.