Timeline of Women’s Suffrage

The road to suffrage was more of a patchwork of fits and starts. It took more than a century for the consensus in support of women’s suffrage to reach the threshold required for an amendment.

The earliest recorded vote legally cast by a woman in America occurred in 1756 in colonial Massachusetts. Though only free men who owned property had voting rights, the town permitted Lydia Chapin Taft, a wealthy widow whose eldest surviving son was younger than voting age, to vote in three Uxbridge town meetings — the first one in favor of appropriating funding for the French and Indian War, and the other two in 1758 and 1765.

1776–1807: The New Jersey experiment

During the country’s nascent years, only five of the original state constitutions explicitly noted that the right to vote belonged exclusively to men. But according to records, in no other state besides New Jersey did women exercise that right.

On July 2, 1776, the same day the Continental Congress unanimously voted for independence from Great Britain, New Jersey adopted its state constitution, with a nondescript “they” buried in the voter qualifications statute. “That all Inhabitants of this Colony of full Age, who are worth Fifty Pounds proclamation Money clear Estate in the same, & have resided within the County in which they claim a Vote for twelve Months immediately preceding the Election, shall be entitled to vote,” the state constitution read.

In 1790 and 1797, the New Jersey Legislature clarified what the state constitution only implied, revising the state’s election statute to include the words “he or she.” That change, which applied only to single women with property, was first adopted in 7 of 13 counties, and then later across the state. Married women had no separate legal existence from their husbands and therefore could not vote. Though it’s difficult to get a complete picture of how many women exercised this right, poll records show that between 1800 and 1806, at least 75 women voted in state and congressional elections in Upper Penns Neck Township.

In 1807, the New Jersey Legislature reversed its progressive stance on voting rights, spurred by growing fears over the political influence of women and Black voters. “After it was reported that women cast nearly a quarter of all votes in the election of 1802, a Trenton newspaper worried that female turnout had reached ‘alarming heights,’” the Brennan Center’s John Kowal and Wilfred Codrington write in The People’s Constitution: 200 Years, 27 Amendments, and the Promise of a More Perfect Union. “The brief experiment with New Jersey’s ‘petticoat electors’ came to an end in 1807.”

That year, more ballots were cast than there were eligible voters in a disputed county election, leading to rampant allegations of voter fraud and new voting restrictions. Responding to public outcry, the New Jersey legislature passed the 1807 Electoral Reform Law, imposing uniform voting rules that abolished the property requirement and limited the franchise to white male taxpayers. In doing so, they baselessly laid the blame for voter fraud squarely onto women, people of color, and immigrants, disenfranchising them once more. By 1844, that change was enshrined by a state constitutional convention, which rewrote the charter to explicitly restrict voting to free white male citizens.

1848: A start in Seneca Falls

While there is debate over whether the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 was truly the start of the women’s suffrage movement, it did mark a significant turning point. The 300-person gathering in upstate New York, attended by renowned abolitionist Frederick Douglass, sought to address women’s inequality and included a radical demand: suffrage. At the convention, Elizabeth Cady Stanton introduced the Declaration of Sentiments, modeled after the Declaration of Independence, demanding for women “immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of these United States,” including the right to vote. The declaration, which became a framework for the suffrage movement, was signed by 68 women and 32 men. The Seneca Falls Convention spawned many other conventions for women’s rights in the years that followed.

In October 1850, the suffrage movement held a two-day national women’s rights convention in Worcester, Massachusetts — the first of a series of annual national convenings. The gathering, which drew almost a thousand attendees who lined the street around Brinley Hall, sought to strengthen the burgeoning movement’s support around the country. An array of notable speakers endorsed the right to vote for women, including Lucy Stone, Sojourner Truth, and Lucretia Mott, among others. Truth, an emancipated slave known for her powerful oratory, spoke specifically to the plight of enslaved women. The convention’s delegates affirmed a resolution pledging solidarity with those enslaved, which stated, “We will bear in our heart of hearts the memory of the trampled womanhood of the plantation, and omit no effort to raise it to a share in the rights we claim for ourselves.” The convention received negative press coverage in the days that followed.

The next convention was held in 1851 in Akron, Ohio. Truth took the stage once more, delivering her acclaimed speech, known as “Ain’t I a Woman.” The speech, ahead of its time, highlighted the intersection of the suffrage and abolitionist movements, weaving together the sexism and racial discrimination suffered by Black women. Two different versions of the speech emerged, leaving open the question of what exactly Truth said. The version that actually includes the iconic question, “Ain’t I a woman?,” was published by suffragist and writer Frances Gage in the New York Independent more than a decade after Truth delivered the speech. The Sojourner Truth Project casts doubt on the fidelity of that version because of the liberties Gage took and the Southern dialect she assigned to Truth, a native New Yorker. The more faithful transcription, according to the project, was published a month after the convention by journalist Marius Robinson in the Anti-Slavery Bugle.

A year after the end of the Civil War, leading suffrage activists, including Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, as well as abolitionists Douglass and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, met in New York City for the 11th National Women’s Rights Convention. The convention unanimously approved a resolution to form the American Equal Rights Association with the goal of working to “secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color, or sex.” The new organization unified the fights for women’s voting rights and civil rights for newly freed Black Americans.

Over the next two decades, the movement found some early success in the West, but it also suffered numerous losses on the ballot and in legislatures. In 1867, a campaign in Kansas to ratify an amendment that would grant equal voting rights for women and Black Americans failed. With it, the strength of a united suffrage movement under the American Equal Rights Association began to falter.

1869: A divided movement

The earliest efforts to secure voting rights for women were deeply intertwined with the fight to end slavery. But in the post–Civil War era, known as Reconstruction, the movement fractured along racial lines. After the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, the 15th Amendment brought those fissures to the fore.

Many suffragists supported a constitutional amendment enfranchising Black men, even if that achievement came before extending voting rights to women. Others in the movement, who long supported suffrage for both women and Black men, rejected the idea that women should step aside. The latter group opposed any change to the Constitution that did not also grant women the right to vote. As Congress debated the 15th Amendment, that divide became particularly fraught, with some white suffragists used racist and anti-immigrant stereotypes to make their case.

For example, a few months after the 15th Amendment passed Congress on February 26, 1869, Stanton, who along with Susan B. Anthony collected signatures in support of the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery, expressed frustration at the exclusion of women’s suffrage in the voting rights amendment. “Think of Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung,” she said at a women’s rights convention, invoking ethnically coded language for Black men, as well as Irish, German, and Chinese immigrants, “who do not know the difference between a monarchy and a republic, who cannot read the Declaration of Independence or Webster’s spelling book, making laws for . . . [noted suffragist] Lucretia Mott.”

After that bitter meeting in May 1869, the American Equal Rights Association was effectively finished and the movement splintered into two factions with competing approaches to suffrage. Stanton and Anthony, representing women who opposed the 15th Amendment’s focus on placing Black men’s suffrage above universal suffrage, formed the National Woman Suffrage Association with the goal of achieving women’s suffrage through a separate federal constitutional amendment. This new group, seen as more radical than its counterpart, pursued a wide-ranging feminist agenda that included not only women’s suffrage but also women’s social equality. Meanwhile, Stone, Harper, and others who backed the enfranchisement of Black men before women created the American Woman Suffrage Association, an explicitly multiracial organization that adopted a state-by-state approach to fulfilling their sole mission: securing suffrage for women.

1872–1913: A new departure and forces rejoined

While the three Reconstruction Amendments did not explicitly enfranchise women, some suffragists advanced a novel interpretation of the 14th Amendment that argued that it implicitly granted them voting rights. Pointing to the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the 14th Amendment, which states, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States,” these suffragists, including Anthony, argued that the right to vote in federal elections was already conferred to women as citizens under the 14th Amendment.

Members of this “New Departure” movement tested their theory at the polls in 1872. Anthony and her three sisters sought to register to vote in their hometown of Rochester, New York. Though it took an hour of vigorous debate and threats of prosecution to persuade the reluctant election inspectors to agree to their request, Anthony and her sisters were among more than a dozen Rochester women who successfully registered to vote on November 1, 1872. City newspapers harshly criticized their actions along with their interpretation of the 14th Amendment, writing, “Citizenship no more carries the right to vote that it carries the power to fly to the moon.”

Over these protests, Anthony and other Rochester women cast their ballots on Election Day — a small victory that led to significant blowback. Anthony was arrested two weeks later and charged with election fraud. She was found guilty and sentenced to pay a $100 fine, which she refused to do. Afterward, she called her trial, in which the judge directed the jury to deliver the guilty verdict, “the greatest judicial outrage history has ever recorded.”

One woman who subscribed to the New Departure theory tested it in the courts. Suffragist Virginia Minor was blocked from voting in the 1872 election by a local registrar in St. Louis, Missouri. In a case that made its way to the Supreme Court, Minor’s husband filed a lawsuit on her behalf, citing the 14th Amendment. In an 1875 ruling, the Court unanimously rejected Minor’s claim, concluding that the right to vote was not guaranteed by citizenship and that states had the power to restrict the franchise to men.

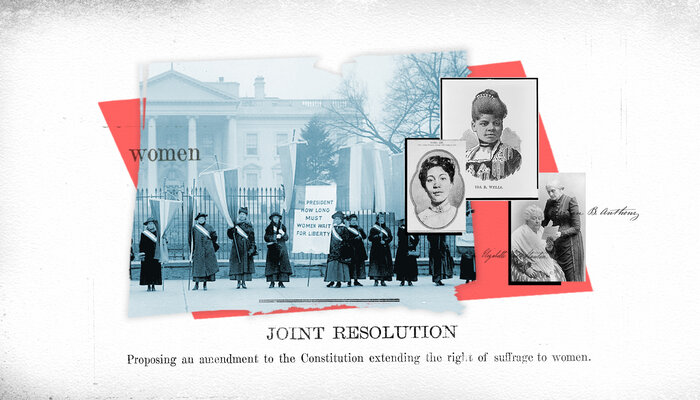

Following that setback, suffrage activists set their sights on Congress. The 19th Amendment was first introduced in Congress by Sen. Aaron Sargent of California on January 10, 1878. It would take more than 41 years for the amendment to secure the necessary two-thirds vote in each house of Congress, but the introduction of the joint resolution, widely known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, was a consequential milestone. For the first time, suffragists were allowed to testify before the members of the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections on the issue, and they flooded the committee with tens of thousands of petitions supporting the amendment. By June, however, the committee recommended that consideration of the amendment be indefinitely postponed, effectively shelving it.

Meanwhile, the piecemeal campaign waged by the American Woman Suffrage Association, Stone’s outfit within the suffrage movement, saw mixed success. Bids to give women the right to vote in the territories of Washington, Nebraska, and Dakota all failed throughout the 1850s and 1860s. But in 1869, Wyoming Territory lawmakers enacted the first women’s suffrage law in the United States, extending the right to vote to women without any restrictions based on property ownership or marital status. The law also allowed women to hold public office, and in 1870, Esther Morris became the first woman in the nation to do so when she was appointed justice of the peace in South Pass City. Twenty years later, women’s voting rights were enshrined in Wyoming’s draft state constitution despite fears that the addition would stand in the way of its push for statehood. Though there was some resistance, in 1890, Congress ultimately agreed to admit Wyoming as the 44th state, making it the first in the union to guarantee universal suffrage.

In Kansas, where a statewide constitutional amendment to grant women the right to vote was defeated in 1867, the suffrage movement shifted its focus to municipal elections, seeking to seat women in local offices. By 1887, an all-female city council was elected in Syracuse and Argonia elected the first woman mayor in the country. Throughout the 1890s, three states in the West — Colorado, Idaho, and Utah — all approved giving women the right to vote.

Amid this limited series of victories in sparsely populated states and territories in the West, and with a constitutional amendment stalled in Congress, the divided suffrage movement rejoined forces. The two competing organizations — the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association — merged in 1890, forming the National American Woman Suffrage Association. The new group, led by Stanton and Anthony in its earliest years, sought to pass an amendment to the U.S. Constitution while also orchestrating state campaigns across the country. By the early 1900s, Anthony handed over the reins to the next generation, hand-picking Carrie Chapman Catt to succeed her as president.

Still, racial fractures continued to bedevil the suffrage movement. Within the National American Woman Suffrage Association, some chapters welcomed Black women and others did not. Notably, state and local chapters barred Black women from attending national conventions held in Atlanta in 1895 and in New Orleans in 1903. On the eve of the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, DC, in which some 5,000 women marched along Pennsylvania Avenue to demand their right to vote, national organizers instructed Black women to march in the back. Ida B. Wells, a Black journalist and activist, openly defied this demand, joining her Illinois state contingent instead.

1916: A younger generation for suffrage

After the 1913 procession, new tension grew inside the movement. A younger generation, frustrated by what they saw as the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s mild-mannered tactics, pursued more militant strategies. In 1912, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, two young suffragists appointed to the organization’s congressional committee, tried to persuade their counterparts to focus solely on a federal amendment instead of a state-based strategy. Paul and Burns formed the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage in 1913 while keeping ties with the National Association.

On the state advocacy front, by 1914, nearly every state and territory in the West adopted women’s suffrage, including California (1911); Arizona, Kansas, and Oregon (1912); and Montana and Nevada (1914). But the rest of the country lagged, as more populous states in the East, including Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania, delivered crushing defeats. The National American Woman Suffrage Association, led by Catt, pursued suffrage through a dual-track strategy known as “The Winning Plan,” which comprised state-by-state organizing and lobbying in the nation’s capital. Catt’s multipronged strategy steadied a fractious movement, directing its focus to sophisticated organizing and lobbying efforts. Her leadership was instrumental in shaping the campaign for suffrage leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment and, ultimately, its ratification.

But for Paul and her allies, that route was taking too long.

In 1916, Paul decided to cut ties with the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and the Congressional Union evolved into the National Woman’s Party, realizing Paul’s vision for an organization dedicated solely to fighting for a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage. The group was known for pushing its cause through militant protests, hunger strikes, and campaigns against politicians who didn’t support suffrage.

Members of the National Woman’s Party rose to national prominence following President Woodrow Wilson’s reelection. Between 1917 and 1919, Paul employed a new and more sensational strategy: peaceful demonstrations outside the White House gates. The women who gathered protested in silence, and later with signs that highlighted the White House’s hypocrisy for supporting democracy abroad in World War I while excluding women from the process at home. They became known as the Silent Sentinels.

After months of daily picketing, Paul, Burns, and dozens of other Sentinels were arrested in October 1917 and sent to Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia, where they continued protesting through hunger strikes. Reports of forced feedings and abuse — including accounts of one November evening, dubbed the Night of Terror, when the women were brutally beaten and terrorized by the guards — drew the attention and sympathy of the public. The suffragists were released later that month. By January 1918, in part due to Catt’s political savvy and Paul’s public pressure, Wilson announced his support for a constitutional amendment during his State of the Union address.

1918–1920: Suffrage at last — for some

With Wilson’s support and 15 states granting equal voting rights to women, the women’s suffrage amendment was reintroduced in the U.S. House of Representatives, where it passed by a two-thirds majority in January 1918. In September of that year, Wilson appeared in the Senate chamber to make a direct appeal for women’s suffrage — a rare move for a president. But the proposal fell two votes short of passage, prompting the National Woman’s Party to launch targeted campaigns against the senators who voted against the amendment. Five weeks later, Democrats lost their majorities in both chambers of Congress in the midterm elections, in part due to their failure to pass the 19th Amendment.

It took several more attempts for both chambers to finally pass the amendment. In the Senate, Southern Democrats represented the most significant hurdle. In May 1919, Wilson called a special session of Congress, which finally secured the necessary two-thirds majorities in both the House and Senate after opponents of the amendment abandoned a filibuster. The House approved the 19th Amendment on May 21, 1919, more than 40 years after it was first introduced. The Senate followed a couple of weeks later on June 4.

The 19th Amendment’s fate was then left to the states. At least 36 states, three-fourths of state legislatures at the time, had to approve the amendment for it to be officially adopted into the U.S. Constitution. Within days of the vote in Congress, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Michigan ratified the measure. By the end of the year, 19 more states, including Texas, followed suit, and 2 states rejected it. (Alabama and Georgia, much like the rest of the South, staunchly opposed giving women equal voting rights.) By March 1920, 35 states had ratified the amendment, but that year, it was rejected by another 6: South Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Mississippi, Delaware, and Louisiana.

After that series of demoralizing losses, the amendment appeared to be seriously in doubt. The 36th ratifying state remained elusive until the ratification process landed in Tennessee. While it wasn’t clear how the legislature would vote, the year before, Tennessee lawmakers had granted partial suffrage to women, allowing them to vote in presidential and municipal elections.

Tennessee Gov. Albert H. Roberts, under pressure from President Wilson, called a special session of the legislature on August 9, 1920. For weeks, activists, organizers, and lobbyists flocked to Nashville, the state capital, all trying to sway lawmakers’ votes one way or the other. Pro-suffrage activists donned yellow roses, while the opposition wore red.

The final vote came on August 18, 1920. The House was deadlocked. Then, State Rep. Harry Burn, a 24-year-old Republican from McMinn County who had initially voted to table — and effectively kill — the suffrage amendment, had a dramatic change of heart. Though he wore the red rose of the “antis” on his lapel, in his pocket he had a letter from his mother, Febb Burn, urging him to “be a good boy” and support ratification. Burn heeded her words and cast the decisive “aye” vote to approve the amendment, and with it, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified. After being accused of taking bribes to switch his vote, Burns explained his decision by saying, “I know that a mother’s advice is always safest for her boy to follow, and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification.”

Post-1920: Struggles after the 19th Amendment was ratified

The road to the 19th Amendment was long and arduous. As Catt said, “To get the word ‘male’ out of the Constitution cost the women of the country 52 years of pauseless campaign.” But for millions of women of color, once the amendment was adopted into the Constitution, the fight for equal voting rights was far from over.

Even with a constitutional right to vote, women of color were not protected against the voter suppression tactics that took hold in the South. Without federal legislation to give more teeth to the 19th Amendment, Southern women of color encountered the same racially discriminatory laws that deterred or blocked Black men from the ballot box. Some states imposed grandfather clauses — a restriction that limited voting rights to those whose grandfathers were able to vote — while others required literacy tests or poll taxes to register to vote. While seemingly neutral, these measures disproportionately disenfranchised voters of color. Additionally, deeply ingrained anti-immigrant fervor, which often translated into racist and xenophobic legislation, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, kept still more people of color out of the democratic process.

It wasn’t until Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the landmark civil rights law aimed at blunting voter suppression, that communities of color were given a more equal opportunity to exercise the franchise. But that progress has been stunted in recent years. Over the last decade, the Supreme Court has significantly weakened the Voting Rights Act, eroding key protections against racial discrimination in voting.