The highly decentralized nature of our election system creates a patchwork of approximately 10,000 jurisdictions at the county or municipal level. At the heart of every one are local election officials, and in many ways they are the unsung heroes of our democracy.

That’s because when they do their jobs well, they often go largely unnoticed. Tens of millions of Americans routinely vote without facing long lines or other challenges, but I’ve never seen see a headline of “Local Election Official Aces Incredibly Complex Technological and Administrative Test.”

To be sure, no election official (or election) is perfect, and one disenfranchised voter is too many. And it’s appropriate to have incredibly high expectations of these stewards of our democracy. But many of the recent public attacks that they are facing are unfair and untrue.

Although I no longer serve as a state election official myself, I am honored to work closely with local and state election officials from the full range of the political spectrum on a number of reforms, from risk-limiting audits to resiliency planning.

Here are five things you may not know about local election officials and the crucial work they do.

1. They work in a nonpartisan or bipartisan fashion to make sure that every eligible vote is counted.

Election officials across the country endeavor to conduct every election in a professional manner. Many take oaths of office, which require a pledge to uphold the federal and state constitutions.

I’ve found that in general, election administration at the local level is much less politicized than one might expect after reading news about the partisan fights between and among federal and state officials. At least one reason for this is likely that state and federal officials aren’t responsible for working directly with voters during elections, whereas local election officials are. More than half of our election officials work in jurisdictions with 5,000 or fewer registered voters.

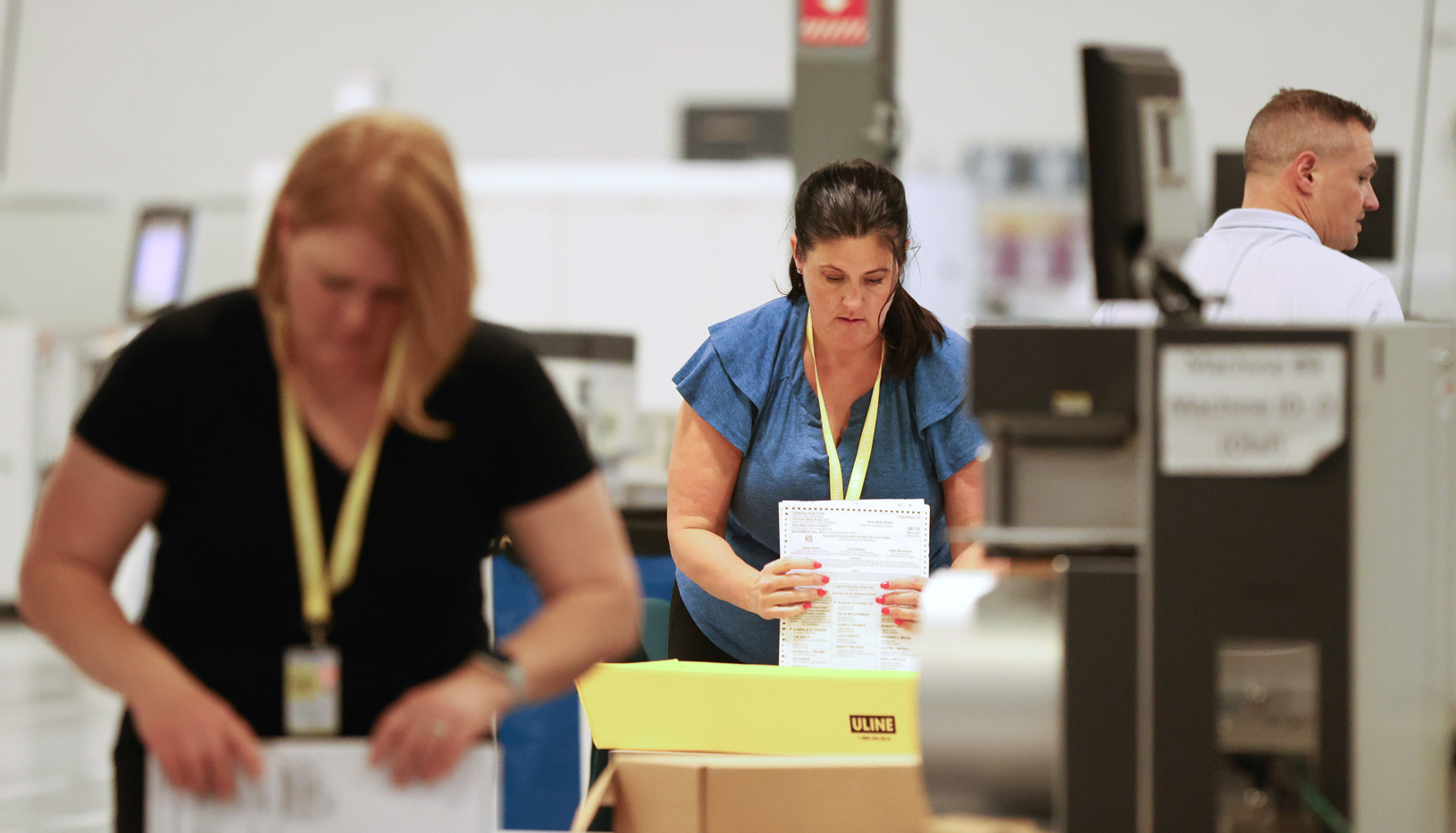

Further, multiple states incorporate balanced partisan representation into various layers of the election administration process. For example, in Arizona, bipartisan teams of one Democrat and one Republican review absentee ballots that tabulators are unable to read and jointly agree on how the ballot should be counted.

2. They don’t make the rules and they don’t set their budgets.

Local election officials are often caught in the middle of conflicts between legislators, courts, and local budget makers. When one of these sides makes a decision, it’s often with little or no input from the local officials who then have to translate the policies into the forms, envelopes, and procedures necessary to actually administer an election.

This year that position has been especially tough as they are tasked with conducting a safe and secure election during a pandemic while implementing ever-changing legislative mandates and judicial decisions, even as some are facing budget cuts. As one election official explained, “Being an election official right now is like being pushed into a batting cage without a bat and all of the pitching machines are aimed at you.”

And this is not a partisan issue. With the pandemic raging, bipartisan groups of local election officials, often joined by their state counterparts, have begged their legislatures for a variety of relief measures. But time after time their requests for common-sense and zero or low-cost solutions, such as authorizing the processing of absentee ballots before Election Day, have been denied.

Even worse, Congress — to be more specific, the Senate — has failed our election officials. The Brennan Center estimates that, due to Covid-19, our election officials are facing an additional $4 billion in costs to conduct safe and secure elections. But the Senate has only agreed to provide one-tenth of what they need. This financial crisis caused at least one local election official to consider paying for plastic shower curtains and PVC pipe out of her own pocket in an effort to keep voters and poll workers safe at the polls.

Moreover, many of the challenges are related to the aging and increasingly frail election infrastructure that is the legacy of years of chronic underfunding at the local, state, and federal level.

3. They must wear many hats but are underpaid.

The typical local election official makes approximately $50,000 annually. Yet the job has become increasingly complex, and they are even subject to occasional death threats.

Today, election officials must be logisticians, cybersecurity experts, communication specialists, legal analysts, and community servants to name just a few of the roles they’re expected to flawlessly fulfill. And this year, many are working seven days a week and through other hardships. One official recently admitted to working from his hospital bed after being diagnosed with Covid-19.

4. They tend to be white and female, but there are encouraging signs that the profession is becoming more integrated and equitable.

There are many reasons for this gender imbalance, but at least one is related to the historical role these officials served, which is still apparent in many of their titles, like clerk, registrar, and recorder. In the past, a significant portion of the job responsibilities could be inelegantly described as “paper pushing,” even though the job has always been best performed by dedicated community servants who deploy strong communications and technical skills. But we’re beginning to see some election officials fight, successfully, to change their official titles to better reflect their current duties. For example, registrars in Virginia may now use director of elections as their title.

The exception to the low pay tends to be in big metropolitan areas. But four of the top five largest election jurisdictions in the country are led by men.

In a promising development, the two newest administrators on this list are people of color. Adrian Fontes was elected as clerk and recorder in Maricopa County’, Arizona, in 2016, and Chris Hollins was just appointed as clerk in June of this year in Harris County, Texas. And we (finally) have a woman of color in the top five: in 2019, Karen A. Yarbrough was sworn in as the first female African American clerk of Cook County, Illinois, the third largest election jurisdiction in the country.

5. Today’s local election officials are tomorrow’s state and federal leaders.

For obvious reasons, serving as a local election official is great preparation for leadership positions in many other areas of government or the private sector. Sen. Roy Blunt, chair of the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, is the former Clerk of Greene County, MO. And Sen. Joni Ernst is the former auditor of Montgomery County, IA.

Several chief election officials in several states, including New Mexico, Washington, and North Carolina, are also former local election officials.

There are many structural safeguards built into our election administration system. The dedicated corps of local election officials are among the strongest, and they deserve our thanks.