American elections face increasingly complex cyber and physical security threats from foreign adversaries, emerging technology, and escalating risks of political violence. Fortifying election systems against these threats is essential.

Historically, state and local governments have been responsible for ensuring the integrity of our electoral system, and that remains true. Decentralized election administration has been a significant source of strength for election security.

But over the past decade, federal support has increased as Congress and federal agencies provided state and local officials with funding and expertise and facilitated information sharing on the threat landscape. As security threats continue to evolve and with election officials now operating as frontline national security figures, that support has helped make U.S. election systems more resilient than ever.

However, the incoming Trump administration may roll back federal support for election security, as outlined in Project 2025. Therefore, it is critical that states step up and reclaim additional responsibilities to ensure our electoral system is protected against threats that experts agree are likely to grow in the coming years.

States should increase personnel support for election officials, providing cyber and physical security expertise to enhance state and local election operations.

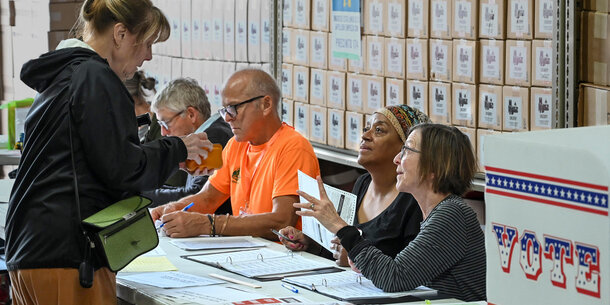

Election officials entered the 2024 cycle amidst a four-year long barrage of attacks, with one in three local election officials saying that they had experienced threats, harassment, or abuse for doing their job. This year, bomb threats targeted at least 67 Election Day polling places, ballot drop boxes were set on fire in three states, election websites faced denial-of-service attacks, and foreign adversaries used fake videos impersonating election workers to cast doubt on election integrity.

While election officials nonetheless administered a fair and secure election in the face of these challenges, these threats will continue to challenge elections in the coming years.

States must ensure that election officials have the support and expertise needed to prepare for and respond to all challenges that threaten to undermine the election process.

- State legislatures should provide funding to launch or expand cyber navigator programs, which hire trained cybersecurity and election administration professionals to work with local election officials and help them assess the security of their systems, identify potential vulnerabilities, and develop tailored strategies to mitigate risk. States can also explore similar support programs that offer technical, operational, communications, and legal capacity to assist local offices without sufficient resources.

- State legislatures should provide funding for physical security assessments and assign a state law enforcement or emergency management agency to conduct these assessments for local election offices.

- State legislatures should provide funding directly to local election offices to hire additional cybersecurity and IT support.

- Peace Officer Standards and Training programs should require law enforcement officers to complete training in election law.

- State legislatures should fund, and state and local officials should support, training exercises between election officials and other critical state and local government partners, including law enforcement and emergency preparedness agencies.

States should increase funding for election officials to upgrade and harden election infrastructure against cyber and physical security threats.

With the aid of over $1 billion in federal Help America Vote Act (HAVA) funding since 2018, states have made remarkable progress in updating voting equipment and other election technology to address long-standing security concerns. Most critically, nearly all votes — 98 percent — were cast on paper in the 2024 election compared to just 82 percent eight years ago.

Decreased federal funding for election security will threaten this progress. Congressional funding for election security has already declined, with just $205 million appropriated since 2020 compared to $805 million in the three years prior. While the Department of Homeland Security attempted to offset this decline by requiring a portion of key grants be spent on election security, this requirement may not continue after 2024.

At the same time, the Election Assistance Commission has released significant updates to federal voting system standards for the first time since 2005 and will be launching first-time standards for other election technology, including electronic pollbooks and voter registration systems. Insufficient funding will deprive election officials of the opportunity to purchase technology that meets these latest security standards.

States must ensure that election officials have the resources needed for modern and secure infrastructure.

- State legislatures and state officials should make use of available unspent federal funds, including HAVA Election Security, Homeland Security Grant Program, and State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program funds, to cover immediate needs.

- State legislatures should provide state and local election officials with additional funding for election infrastructure, including:

- Upgrades to voting equipment, electronic pollbooks, voter registration databases, and other election technology, to ensure this technology meets the latest federal security standards

- Improved physical security of election offices, warehouses, counting facilities, and polling places.

States should support cross-jurisdictional information sharing networks and boost voter education efforts.

As election security has emerged as a national threat, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and other federal agencies have improved information sharing between the federal, state, and local levels to ensure election officials understand and are prepared to respond to cyber and physical security risks. These efforts include convening public and private sector leaders to provide interagency and cross-jurisdictional coordination on security risks and funding the Elections Infrastructure Information Sharing & Analysis Center (EI-ISAC) to reach and support frontline election officials across the country.

But these information sharing efforts, not only by the federal government but private companies and researchers as well, have faced political attacks in recent years, leading to diminished capacity to track election falsehoods, communicate across public and private sectors, and get accurate information to election officials and voters. This rollback has occurred even as artificial intelligence technology has made it easier than ever to imitate authoritative sources and deceive the public. These new threats posed by AI require additional support from state legislatures to fund voter education on the topic.

States must protect and expand information sharing capacity and voter education capacity.

- State and local officials should join and support existing cross-jurisdictional information sharing networks, including state and national election official associations and EI-ISAC.

- State legislatures should provide funding for voter education campaigns to inform the public on how elections work and to prepare the public to understand and identify deceptive AI-generated communications.