Introduction

The gap in voter participation between Black and white Americans decreased following the civil rights revolution of the 1960s. Unfortunately, our research shows that for more than a decade, this trend has been reversing. This report uses data to which few previous researchers have had access to document the racial turnout gap in the 21st century.

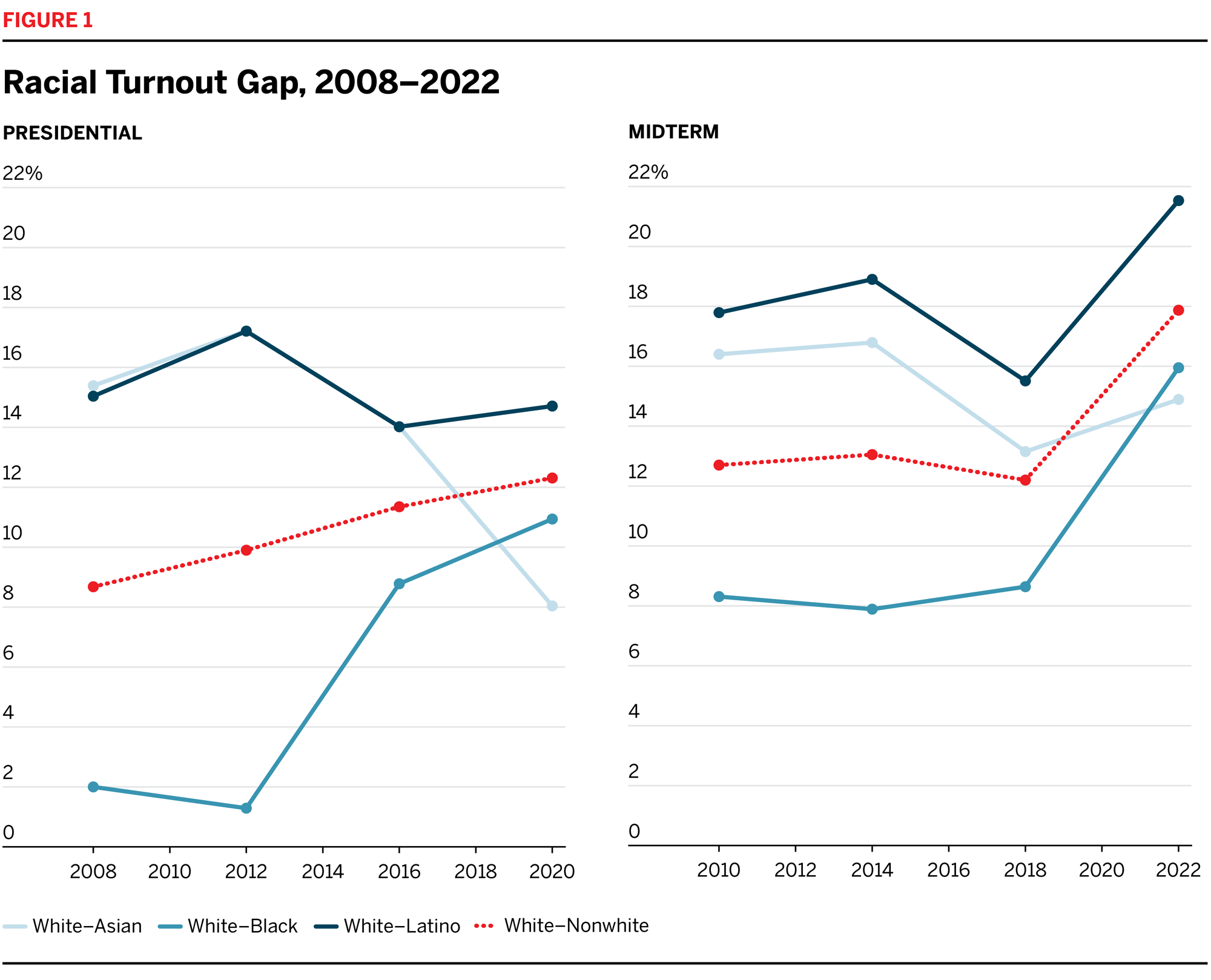

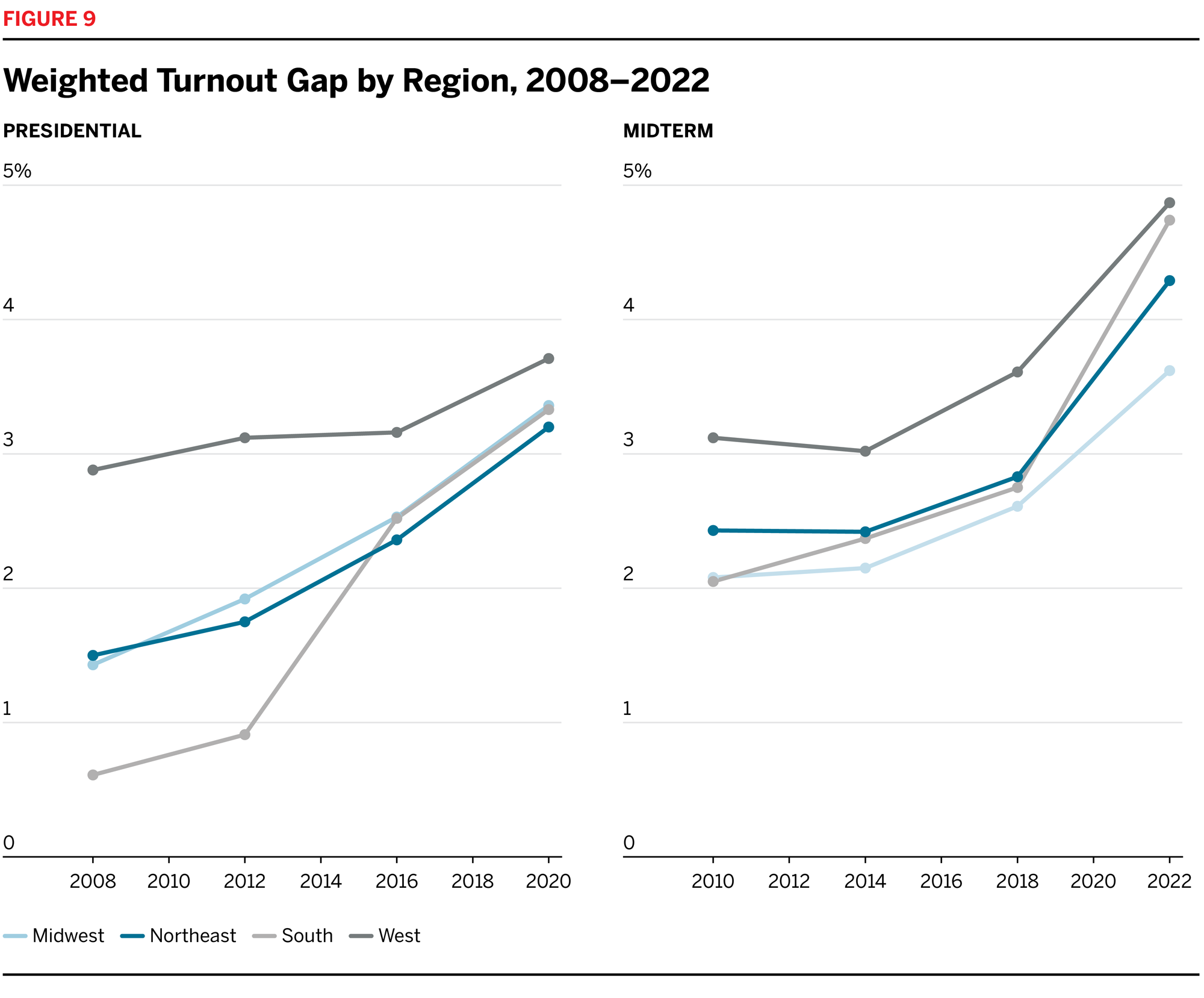

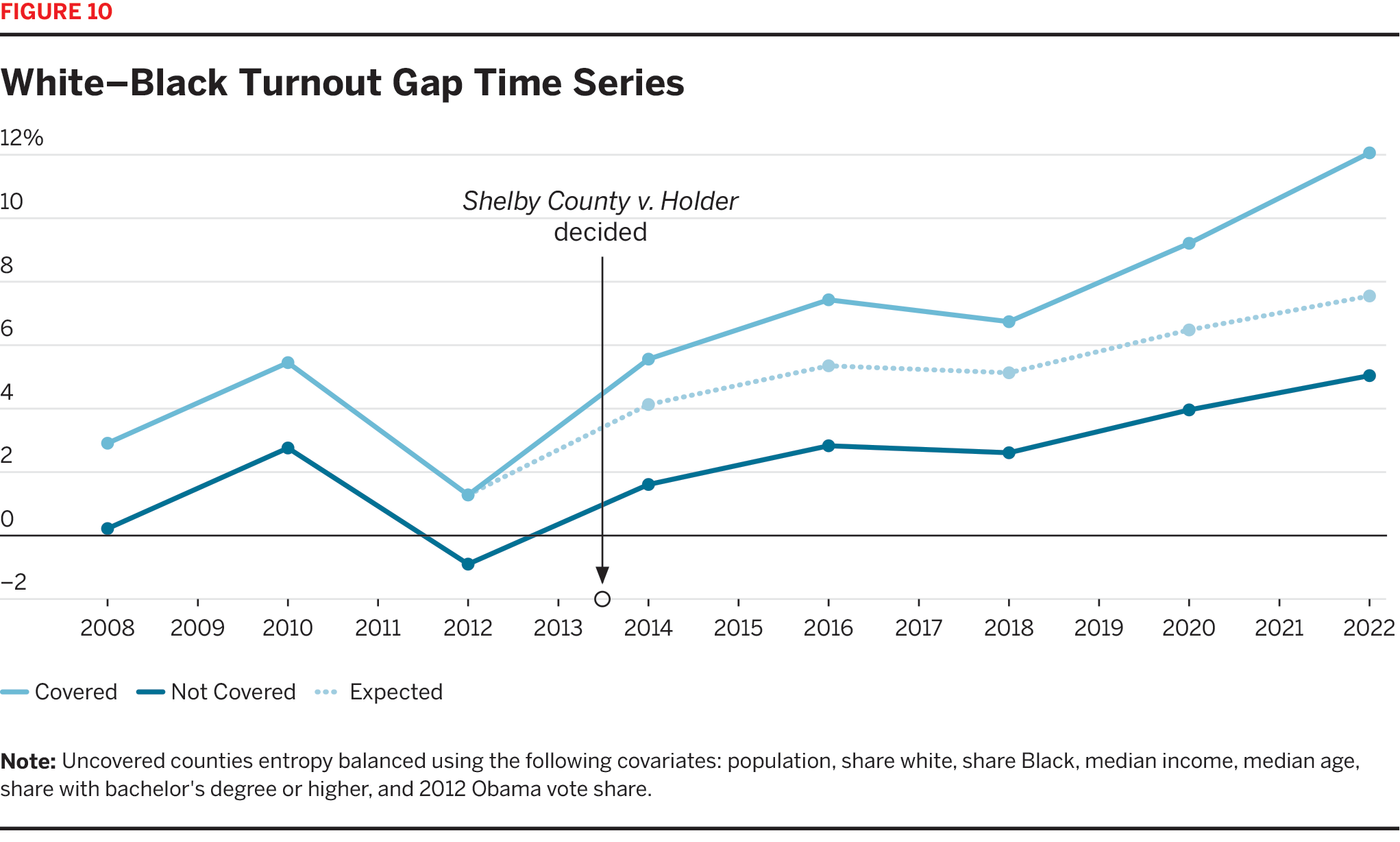

The racial turnout gap — or the difference in the turnout rate between white and nonwhite voters — is a key way of measuring participation equality. We find that the gap has consistently grown since 2012 and is growing most quickly in parts of the country that were previously covered under Section 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which was suspended by the Supreme Court in its 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder. 1

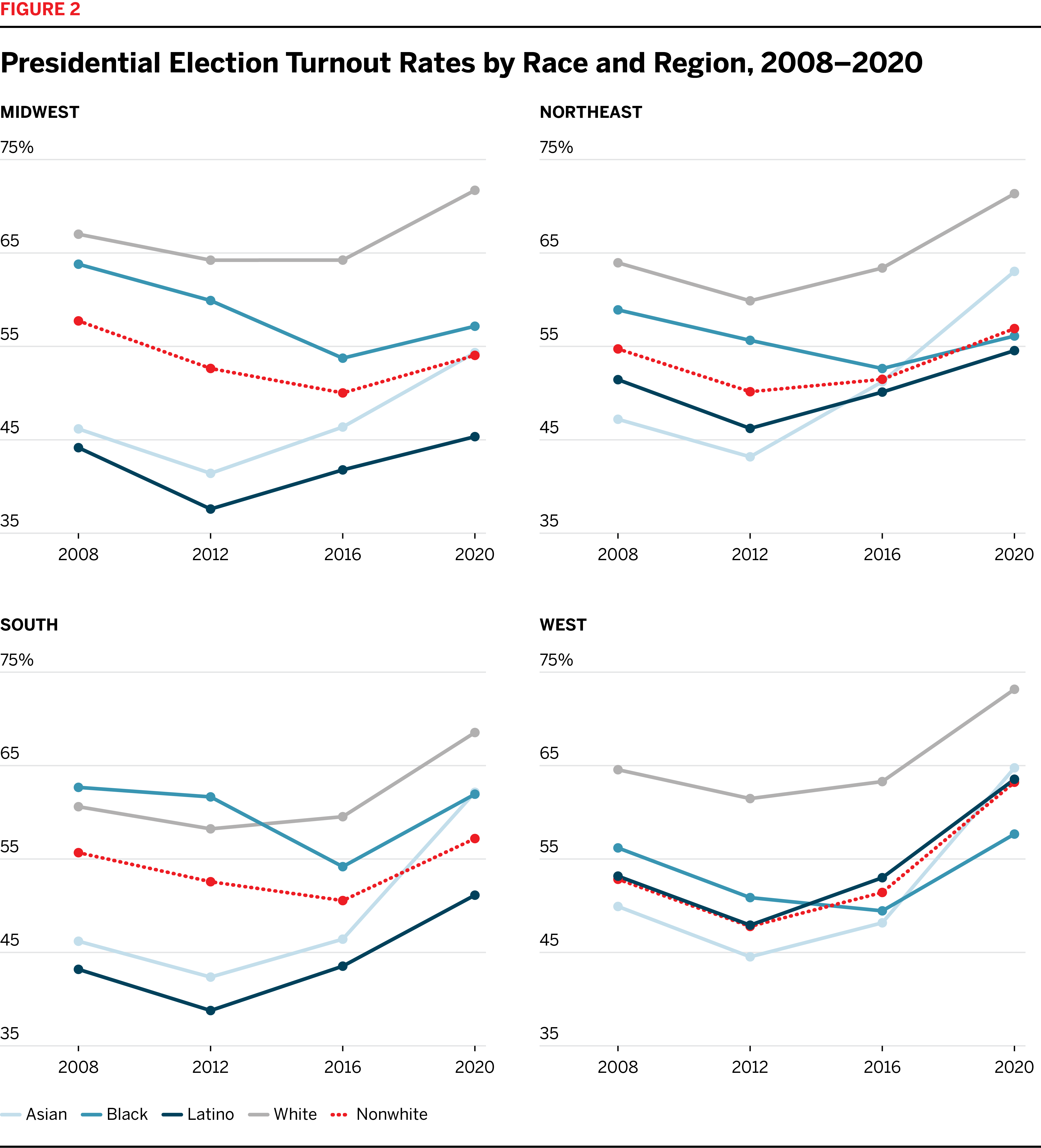

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act required jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination in voting to “preclear” any changes to their voting policies and practices with the U.S. Department of Justice (or federal courts). In the Supreme Court’s Shelby County decision, Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, argued that Congress had not established that the formula used to determine the jurisdictions that would be subject to preclearance (found in Section 4b) was reflective of current political realities and that the formula was thus unconstitutional. While the Court agreed that the original coverage formula’s reliance (in part) on low turnout was justified in the 1960s and 1970s, the narrow majority concluded that contemporary turnout gaps should be used to assess current coverage under Section 4b. The Court relied heavily on turnout rates to substantiate its argument, writing that in the 2012 presidential election, “African-American voter turnout has come to exceed white voter turnout in five of the six States originally covered by §5.” But this interpretation of the data was far too narrow: the low turnout gaps in 2012 were likely due to Barack Obama’s presidential candidacy and did not demonstrate that preclearance was no longer needed. 2 That moment, on its own, was unrepresentative of the general pattern showing a sustained, and now growing, racial turnout gap.

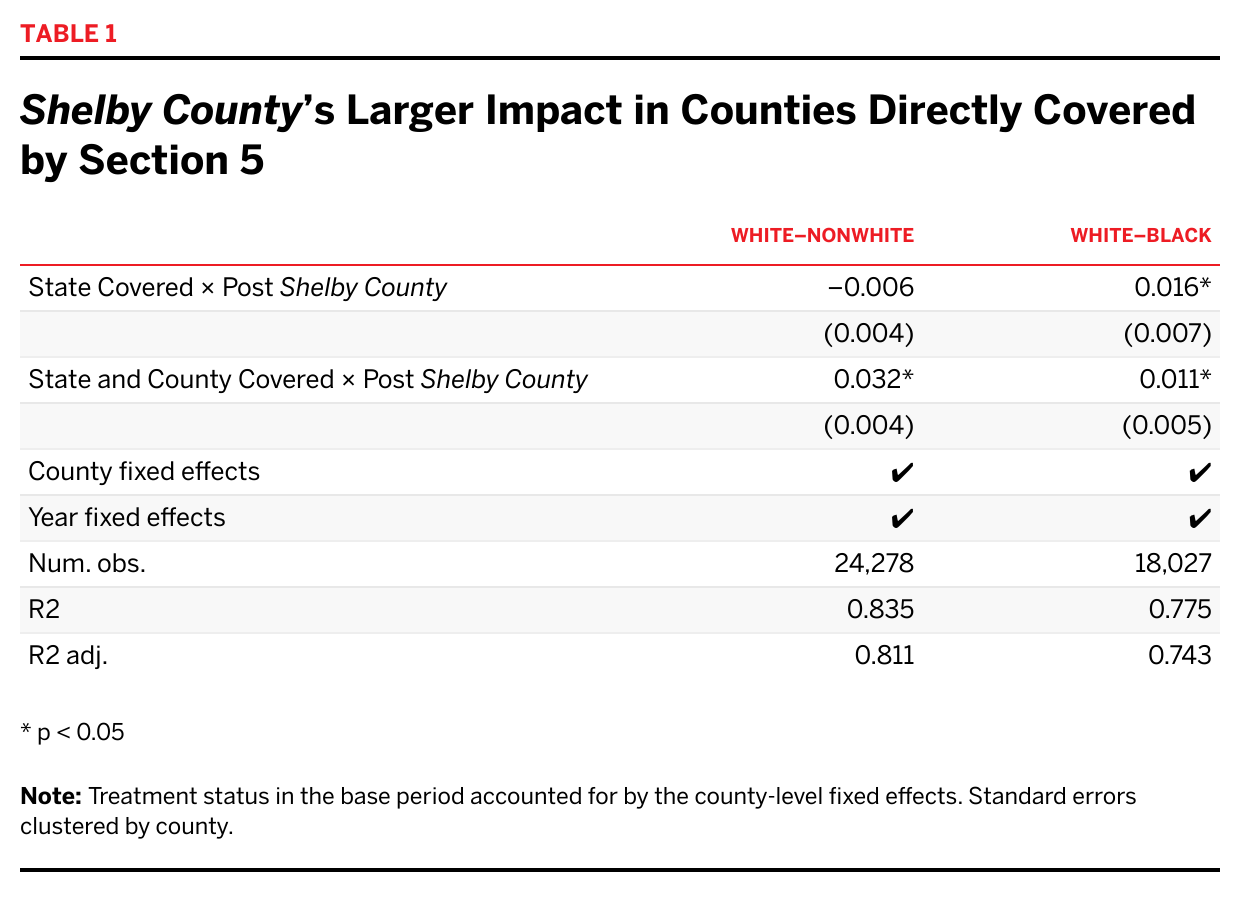

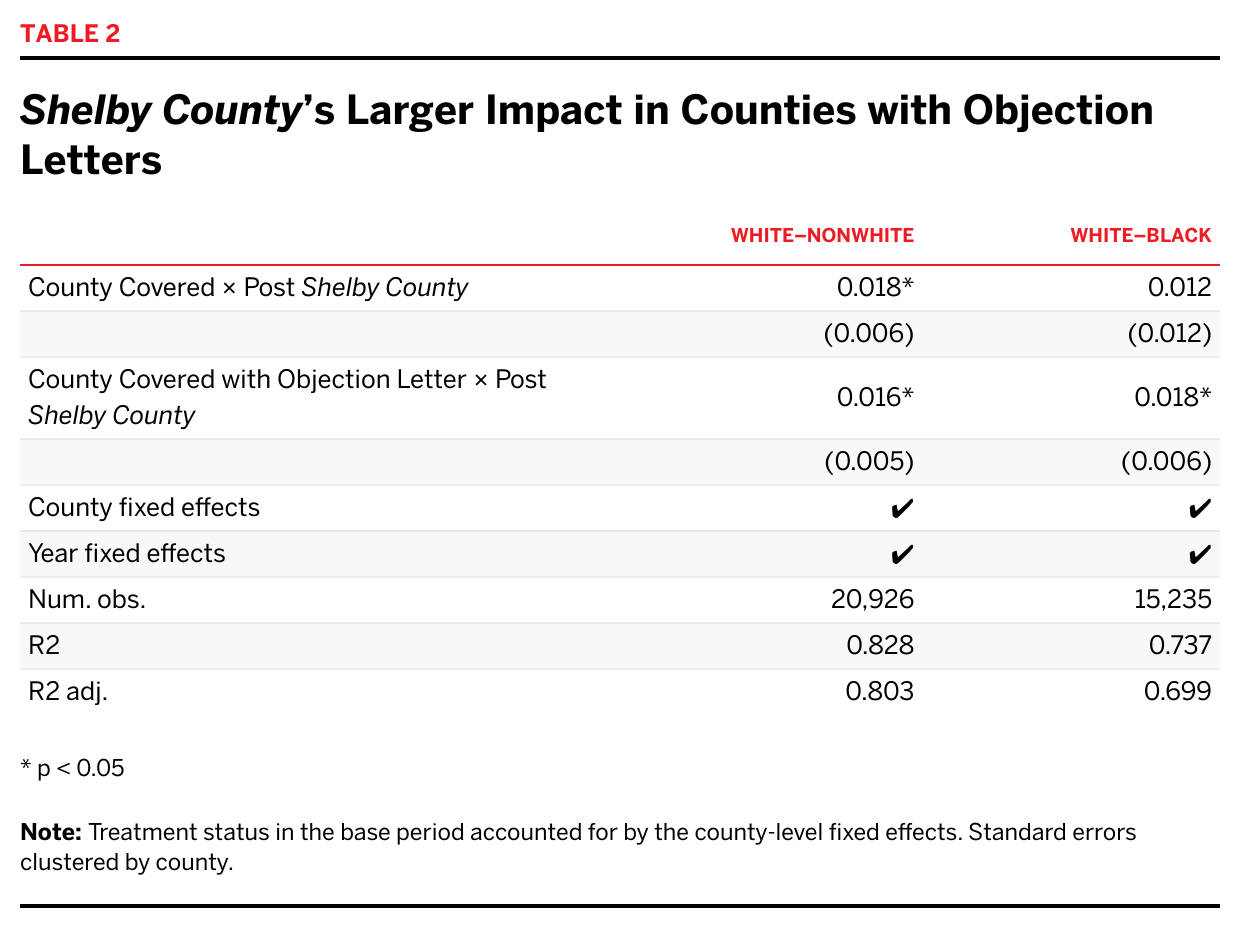

In this report, we assess how the racial turnout gap has evolved in the decade since the Court’s decision. We find that while the gap is growing virtually everywhere, Shelby County had an independent causal impact in regions that were formerly covered under Section 5. By 2022, our primary models indicate that the white–Black turnout gap in these regions was about 5 percentage points greater than it would have been if the Voting Rights Act were still in full force, and the white–nonwhite gap was about 4 points higher. Put differently: the turnout gap grew almost twice as quickly in formerly covered jurisdictions as in other parts of the country with similar demographic and socioeconomic profiles.

Recent scholarship finds that restrictive voting laws generally limit the turnout of voters of color the most. 3 But while the research documents the effects of individual policies like polling place consolidation and voter identification laws, less is known about how the effects of these policies compound as more restrictions on voting are enacted. 4 Moreover, many policies and practices that drive voting are not codified in state law. Take, for instance, voter list maintenance practices: following the Shelby County decision, jurisdictions that previously had been required to preclear any changes to voting with the federal government dramatically increased the rate at which they removed voters, even if state laws governing list maintenance did not change. 5 We cannot identify and measure the impact of each individual change to voting policies and practices across the country, but the racial turnout gap necessarily takes account of all changes in voting policy, statutory or otherwise. Our unique data set, collected from nearly 1 billion vote records, allows us to conduct this analysis for the first time.

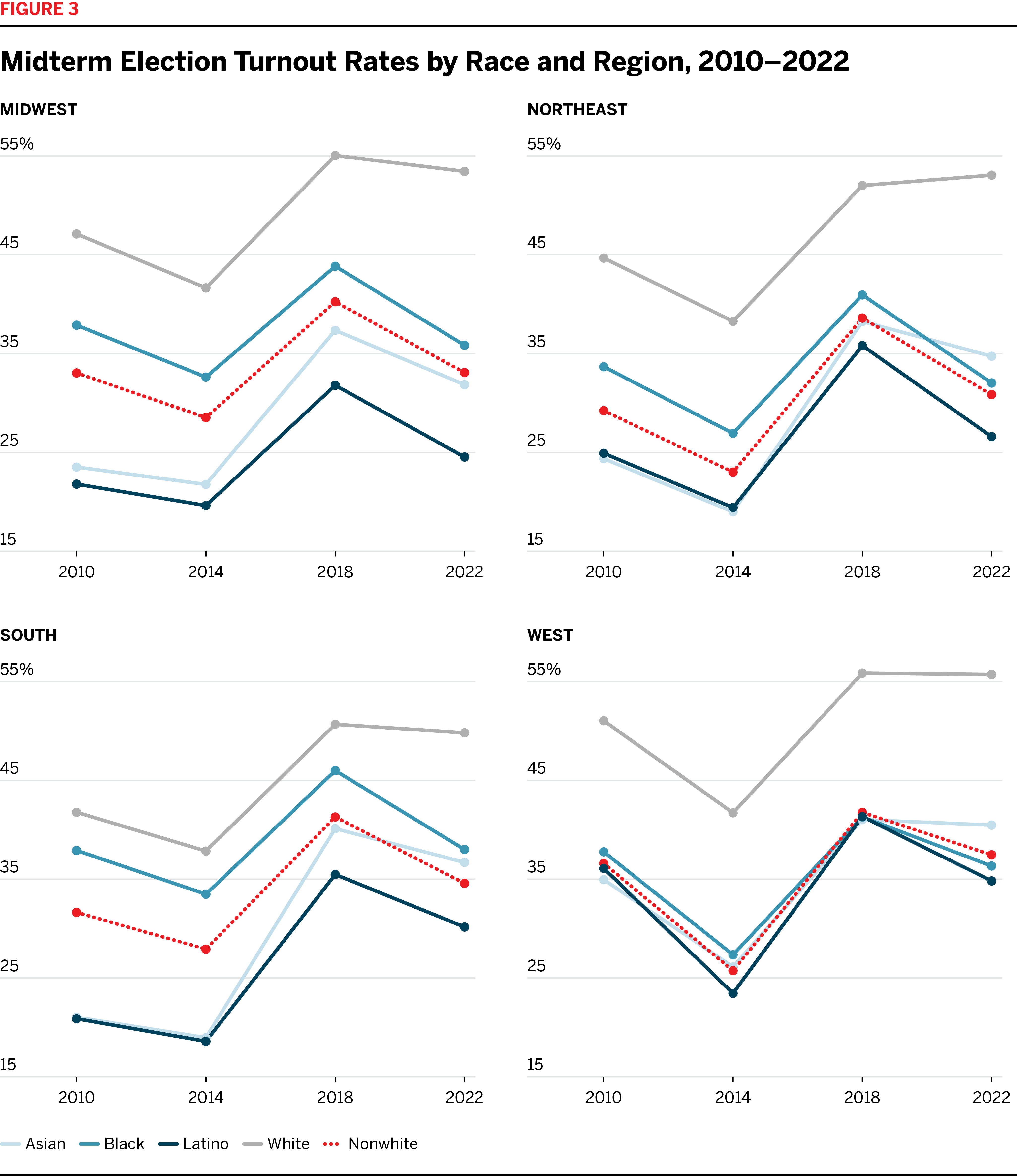

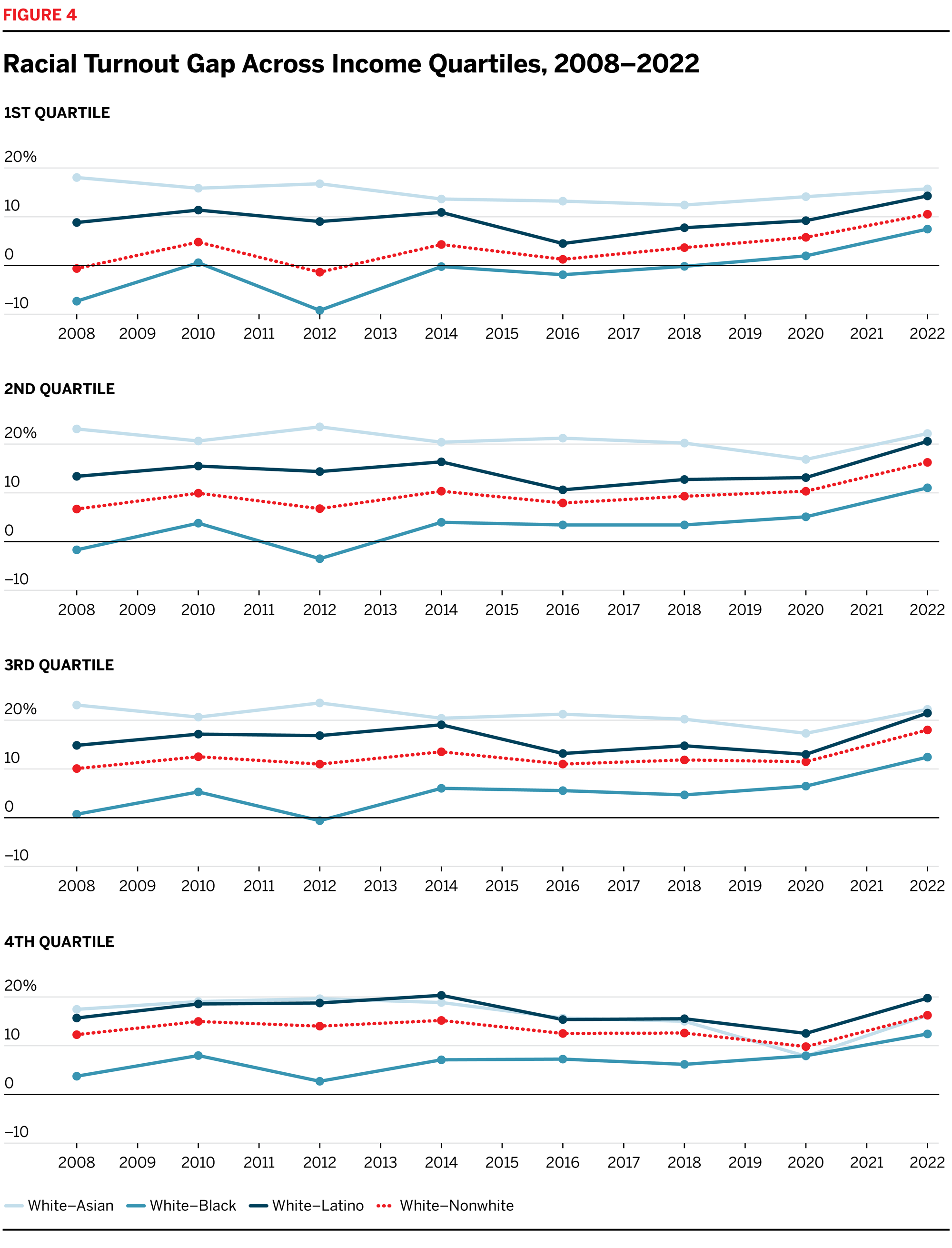

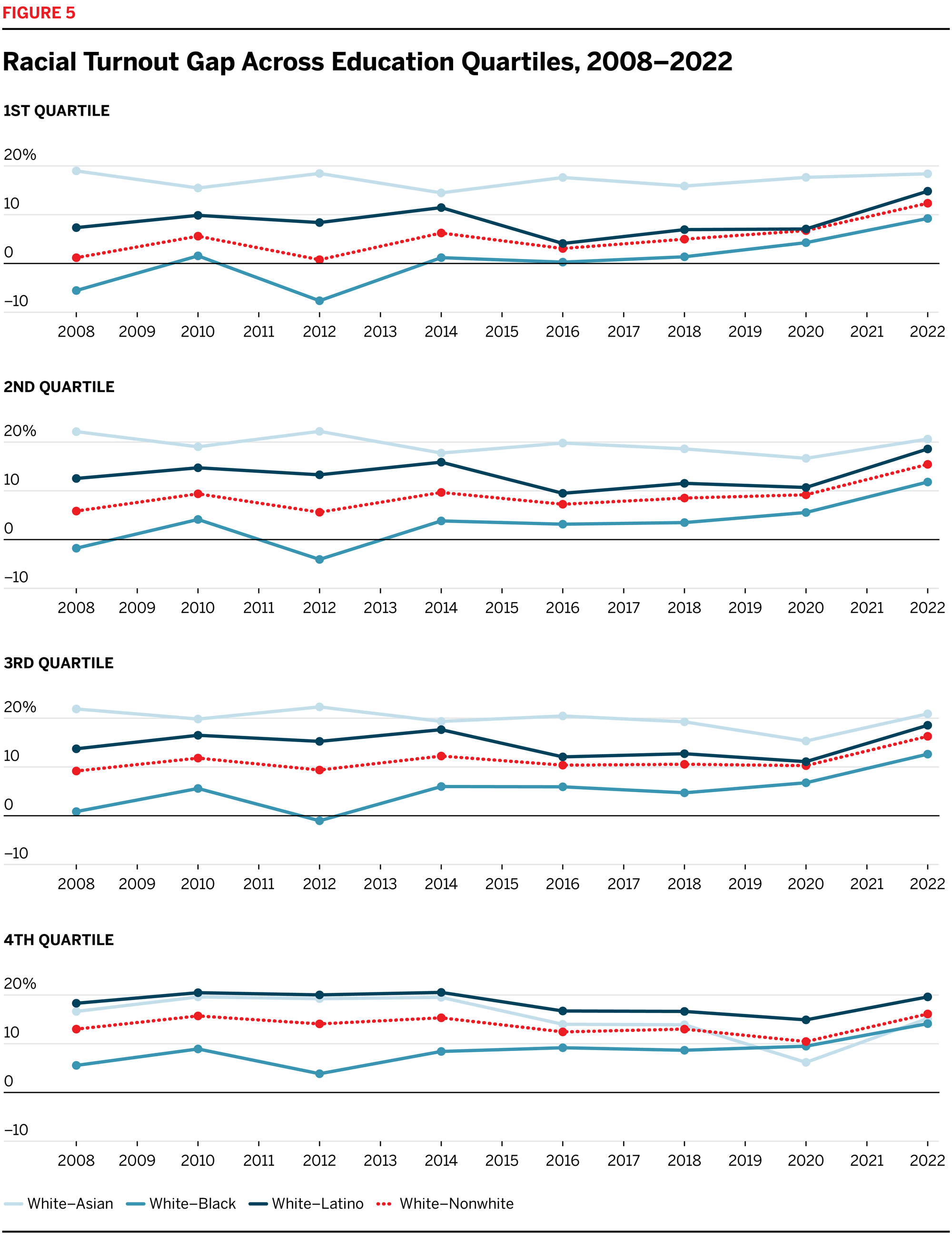

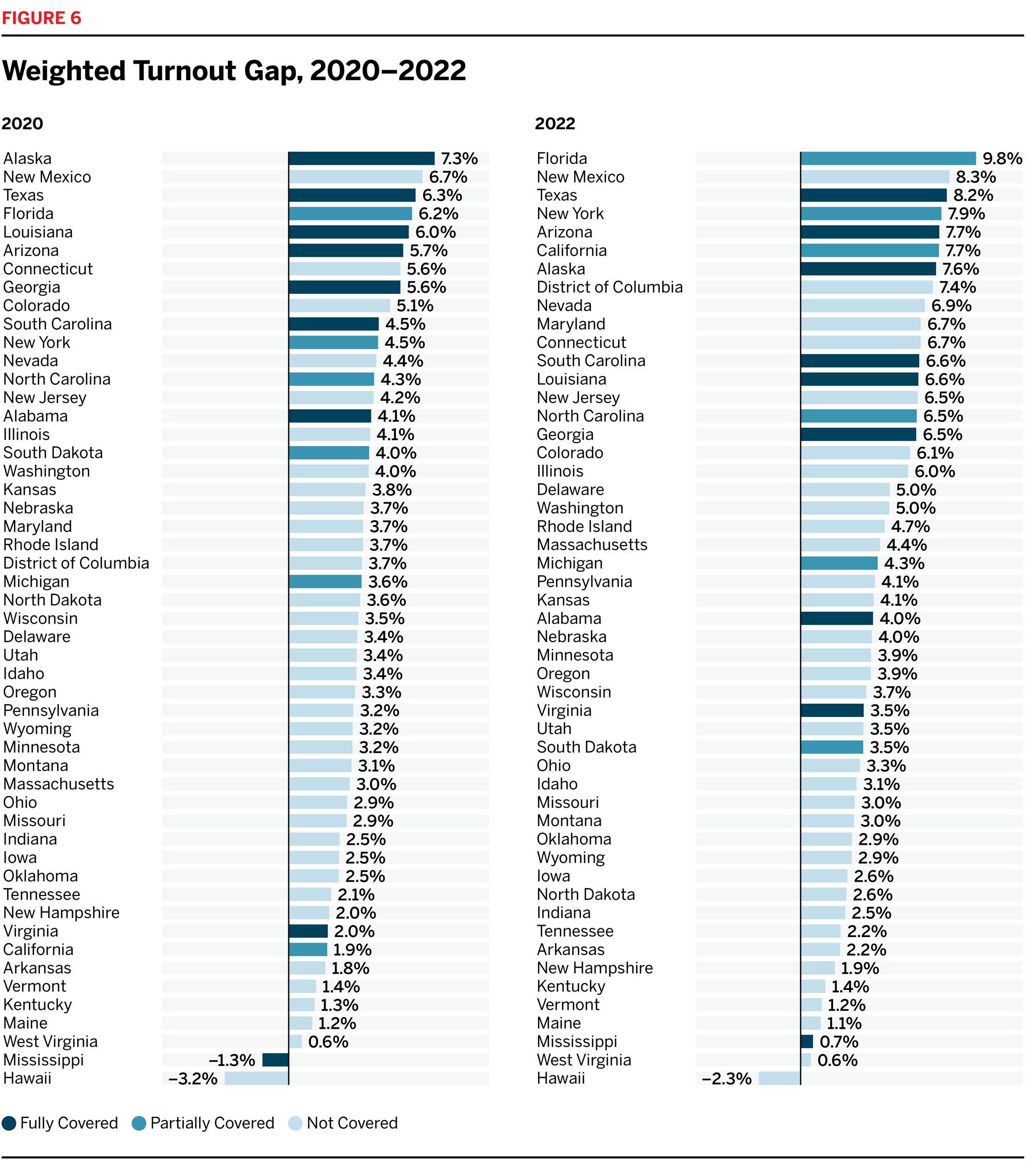

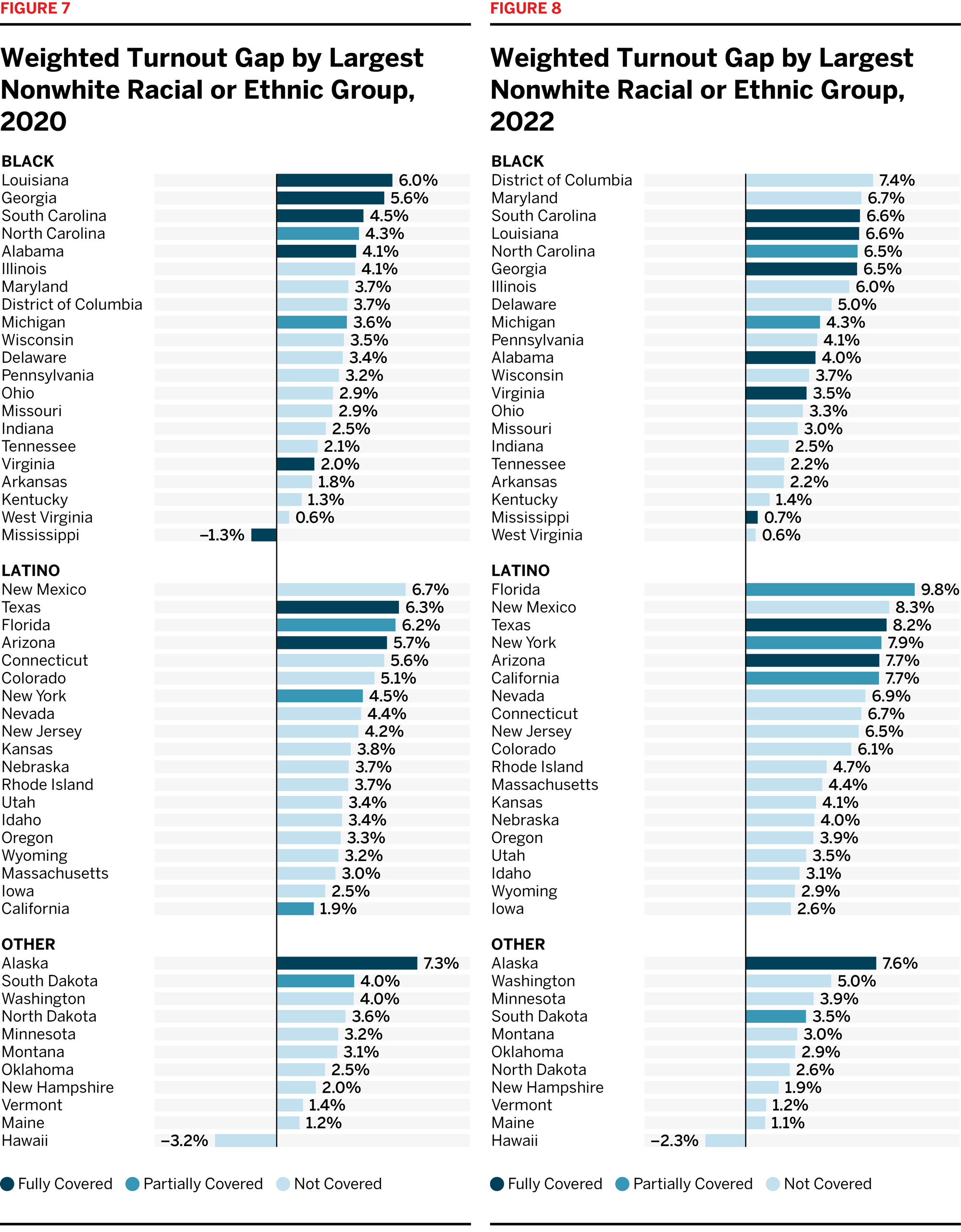

This report uses voter file snapshots from shortly after each of the past eight federal elections from Catalist and L2 to estimate turnout rates by race. Catalist and L2 are respected firms that sell voter file data to campaigns, advocacy groups, and academic institutions. Our conclusions based on this body of information about individual-level turnout behavior far surpasses what previous researchers have been able to establish working from limited survey data. We show that the racial turnout gap has grown everywhere. In all regions, the gap in the 2022 midterms was larger than in any midterm since at least 2006. In 2022, white Americans voted at higher rates than nonwhite Americans in every single state besides Hawaii. Moreover, the turnout gap cannot be entirely explained by socioeconomic differences — in income or education level — between Americans of different races and ethnicities.

That gap costs American democracy millions of ballots that go uncast by eligible voters. It also has significant consequences for political candidates and their campaigns. In 2020, if the gap had not existed, 9 million more ballots would have been cast — far more than the 7 million by which Joe Biden won the national popular vote. In 32 states, the number of “uncast” ballots due to the turnout gap was larger than the winning presidential candidate’s margin of votes. 6 That’s not to say that the racial turnout gap necessarily changed electoral outcomes in any given state, but the immensity of this figure does put the magnitude of the turnout gap into greater perspective. The gap matters for our political system.

Given that the racial turnout gap is growing around the country, including in regions that weren’t covered by Section 5, Shelby County’s impact is not immediately clear. The widening of the gap nationally can’t be directly attributed to the Supreme Court’s decision, though the Court perhaps emboldened jurisdictions that were not subject to preclearance to enact new restrictive policies. 7 However, the turnout gap — especially the white–Black turnout gap — is growing more quickly in counties that were formerly subject to Section 5 than in other, comparable parts of the country. A variety of statistical approaches support the conclusion that this more rapid growth in the turnout gap is attributable to the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County.

In addition, the effect of Shelby County has been growing over time; the decision did not result in a one-time increase. Instead, the difference between formerly covered and other jurisdictions was larger in 2022 than in any election since the decision was handed down. Meanwhile, with the federal government unable to protect the political rights of people of color using the full power of the Voting Rights Act, the laws and practices that would have been subject to preclearance continue to accumulate. 8

Endnotes

-

1

Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529 (2013). -

2

Lawrence Bobo and Franklin D. Gilliam, “Race, Sociopolitical Participation, and Black Empowerment,” American Political Science Review 84, no. 2 (1990): 377–93, https://doi.org/10.2307/1963525; and Ebonya Washington, “How Black Candidates Affect Voter Turnout,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 121, no. 3 (2006): 973–98, https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.121.3.973. -

3

Anna Baringer, Michael C. Herron, and Daniel A. Smith, “Voting by Mail and Ballot Rejection: Lessons from Florida for Elections in the Age of the Coronavirus,” Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy 19, no. 3 (2020): 289–320, https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2020.0658; Bernard L. Fraga and Michael G. Miller, “Who Do Voter ID Laws

Keep from Voting?,” Journal of Politics 84, no. 2 (2022): 1091–1105, https://doi.org/10.1086/716282; John Kuk, Zoltan Hajnal, and Nazita Lajevardi, “A Disproportionate Burden: Strict Voter Identification Laws and Minority Turnout,” Politics, Groups, and Identities 10, no. 1 (2022): 126–34, https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2020.1773280; and Enrijeta Shino, Mara Suttmann-Lea, and Daniel A. Smith, “Determinants of Rejected Mail Ballots in Georgia’s 2018 General Election,” Political Research Quarterly 75, no. 1 (2022): 231–43, https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912921993537. -

4

Kevin Morris and Peter Miller, “Authority After the Tempest: Hurricane Michael and the 2018 Elections,” Journal of Politics 85, no. 2 (2023): 405–20, https://doi.org/10.1086/722772; and Fraga and Miller, “Who Do Voter ID Laws Keep from Voting?” -

5

Jonathan Brater et al., Purges: A Growing Threat to the Right to Vote, Brennan Center for Justice, 2018, https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/purges-growing-threat-right-vote. -

6

David Wasserman et al., “2020 Popular Vote Tracker,” Cook Political Report, 2020, https://www.cookpolitical.com/2020-national-popular-vote-tracker. -

7

Further, by putting the burden on advocates to monitor changes in policy and bring Section 2 cases in all 50 states, the decision made it more likely that a change in a non-covered jurisdiction would go unnoticed or unchallenged. Section 2 prohibits any electoral practice that minimizes the voting strength of a racial or ethnic group. -

8

J. Morgan Kousser and others have documented the central role that the federal government must play in promoting and safeguarding multiracial democracy in the United States. See J. Morgan Kousser,

Colorblind Injustice: Minority Voting Rights and the Undoing of the Second Reconstruction (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), https://uncpress.org/book/9780807847381/colorblind-injustice; and Jacob Grumbach, Laboratories Against Democracy: How National Parties Transformed State Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2hbr28q.