Cases on Presidential Powers and Executive Authority

Article II of the Constitution presents only a barebones outline of the duties, rights, and privileges of the executive branch, including the office of the president, so Congress and the Supreme Court have wide latitude to define the scope and limitations of executive power. Debates over the president’s authority and privilege often arise when the country finds itself embroiled in national emergencies, war, and — perhaps most famously during the Nixon administration — corruption scandals.

Little v. Barreme

In 1799, during the Quasi-War with France, Congress imposed an embargo on trade with the nation and authorized President John Adams to direct the navy to stop and seize any American vessels sailing to French-controlled ports. Adams, however, went a step further and directed the navy to capture any ships suspected of traveling to and from French ports.

Soon afterward, Commander George Little of the U.S.S. Boston intercepted a ship called the Flying Fish, which was departing the French-controlled port of Jeremie (in present-day Haiti) with a cargo of coffee. Little suspected the ship was American and violating the embargo, partly because the ship’s captain looked American and spoke perfect English, so he detained the crew. However, he learned that the vessel was Dutch, the captain was Prussian, and the cargo was neutral. The crew was released, but a court initially found that they weren’t entitled to damages for their improper detention because Little had reason to believe that the Flying Fish was American. On appeal, however, a court ruled that Little had no right to seize the ship and owed damages to the illegally captured crew.

The Supreme Court was eventually asked to determine both the legality of the Flying Fish’s seizure and the question of damages.

In a unanimous decision, the Court ruled against Little and held him liable for damages. Moreover, the Court held that the seizure would have been illegal even if the ship had been American. The opinion by Chief Justice John Marshall maintained that despite being commander in chief, the president did not have the power to order the navy to seize ships leaving French ports when Congress had only authorized the seizure of ships en route to French ports. The ruling helped define the bounds of presidential power in military matters.

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer

At the height of the Korean War, unionized steel mill workers threatened to strike after companies refused to meet their demands for higher wages. President Harry Truman worried that a disruption in steel production could jeopardize the war effort. He urged Congress to authorize a government takeover of the steel mills, but his plan failed to garner enough support, with lawmakers warning that encouraging federal intervention in labor disputes could set a dangerous precedent.

Over Congress’s objections, Truman issued an executive order hours before the strike was set to begin on April 9, 1952. He instructed Secretary of Commerce Charles Sawyer to seize most of the nation’s steel mills and keep them running. The steel company presidents were ordered to operate as directed by the secretary until further notice.

The companies quickly challenged the takeovers, arguing that Truman’s actions were an overreach of presidential authority and infringed on their constitutional property rights. Though the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia initially granted the companies an injunction blocking the takeover, the DC Circuit Appeals Court reversed this decision, allowing the government to keep control of the steel mills while the Supreme Court heard the case. Truman boasted in a letter to Congress that despite lawmakers’ inaction, he had ensured that steel production continued and that workers stayed on the job “even though the companies and the union had no collective bargaining contract.”

On June 2, 1952, however, the Supreme Court issued a 6–3 decision against the steel mill takeovers. Justice Hugo Black’s majority opinion stated that the president lacked the authority to sidestep Congress and unilaterally seize control of private industry or intervene in labor disputes. While the three dissenting justices raised concerns about hampering the president’s ability to act decisively during times of crisis, Black argued that “the Founders of this Nation entrusted the lawmaking power to Congress alone in both good and bad times.”

The most influential part of the decision, however, is the three-part test articulated in Justice Robert Jackson’s concurrence. Jackson identified three zones of executive power. First, when the president acts with Congress’s express or implied authorization, his powers are at their maximum; if his actions are unconstitutional, it is because “the Federal Government, as an undivided whole, lacks [the] power” to take those actions. Second, when the president acts in the face of congressional silence, he must rely on his own independent powers — or, when acting in the “zone of twilight” where the president and Congress share power, the courts will ask whether circumstances indicate congressional quiescence. Third, if the president’s actions are contrary to the express or implied will of Congress, the courts will sustain the actions only if the president’s power is “conclusive and preclusive” (that is, the president has power over the subject but Congress does not).

The Youngstown ruling solidified that presidential powers are not absolute and must be grounded in the Constitution or statutory law. It remains a cornerstone decision in our understanding of checks and balances and the limits on executive authority, even during times of crisis.

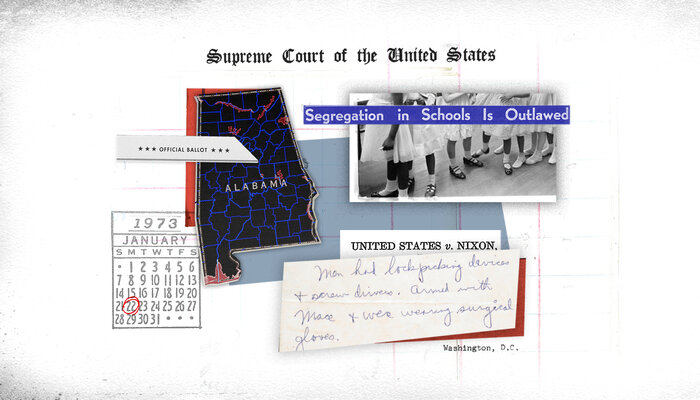

United States v. Nixon

In the summer of 1974, President Richard Nixon was in legal hot water. A grand jury had indicted seven members of his administration and reelection campaign, including his attorney general, for their role in the Watergate scandal. A special prosecutor investigating the break-in at the Democratic Party’s Watergate headquarters filed a subpoena to access Nixon’s secret recordings of Oval Office conversations known as the “White House tapes.” These were widely believed to be the smoking gun connecting Nixon to the cover-up of his administration’s involvement in the burglary and the obstruction of the FBI’s investigation.

Nixon refused to hand over the tapes, arguing that executive privilege allowed him to keep confidential the communications of the executive branch and granted him immunity from judicial review. The question went to the Supreme Court, which had to return from its summer recess to hear the historic case.

In a unanimous decision, the Court ruled against Nixon, rejecting his claim to absolute presidential privilege and ordering him to produce the tapes. Confidentiality, wrote Chief Justice Warren Burger, “cannot prevail over the fundamental demands of due process of law in the fair administration of criminal justice.” Nonetheless, legal experts acknowledge that the decision in some ways significantly expanded executive power, as it was the first time the Supreme Court recognized the existence of executive privilege, which had been a controversial proposition for decades.

Guantanamo Bay Cases

In the wake of 9/11, President George W. Bush launched the War on Terror to dismantle terrorist networks and prevent future attacks. During the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, U.S. and allied forces captured hundreds of individuals, often with little evidence to suspect that they were members of al-Qaeda or the Taliban, and detained them at the U.S. naval base of Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The legality of these detentions, the rights of the detainees, and the interrogation methods used were called into question in four pivotal Supreme Court cases that examined how to balance national security with individual liberties.

Hamdi v. Rumsfeld

In 2001, U.S. troops detained American citizen Yaser Hamdi in Afghanistan for allegedly fighting for the Taliban. Initially held at Guantanamo Bay, Hamdi was designated an enemy combatant — a legal status used by the George W. Bush administration to enable the military to indefinitely detain individuals. In addition, they were deemed to be “unlawful” combatants, thus allowing the administration to argue they were not entitled to the rights typically afforded to prisoners of war under the Geneva Conventions.

Three months into his detention, officials transferred Hamdi to a Virginia military prison after learning he was a U.S. citizen. Hamdi argued that detaining him indefinitely and denying him access to an attorney and a trial violated his Fifth Amendment due process rights. On Hamdi’s behalf, his father filed a writ of habeas corpus, in which a person asks a court to decide if they have been wrongfully detained. The government defended its actions on national security grounds, arguing that courts should defer to the executive branch’s wartime decisions.

In 2004, the Supreme Court ruled in a 6–3 decision that U.S. citizens retain their due process rights and habeas corpus protection, even if declared enemy combatants. Accordingly, they must be granted a meaningful opportunity to contest the factual basis for their detention before a neutral decisionmaker. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote, “A state of war is not a blank check for the President when it comes to the rights of the Nation’s citizens,” affirming that courts’ role in checking the executive branch is crucial even in wartime.

Rasul v. Bush

On the same day the Court ruled on citizen detainees, it handed down a ruling addressing whether non-U.S. citizens held at Guantanamo Bay could also challenge their detention.

The families of four noncitizens held at Guantanamo filed habeas petitions under a statute authorizing courts to hear such claims, arguing that their indefinite detention without charges or judicial review violated their due process rights. The government contended that, because the detainees were being held in Cuba, U.S. courts lacked jurisdiction under the habeas statute.

The Supreme Court disagreed, ruling 6–3 in consolidated cases known as Rasul v. Bush that while Cuba had sovereignty over its territory, the U.S. government had complete jurisdiction and control over the Guantanamo base, meaning detainees had a statutory right — one that did not depend on their citizenship — to challenge their detention in U.S. courts.

Hamdan v. Rumsfeld

Yemeni citizen Salim Ahmed Hamdan, Osama bin Laden’s driver, was captured in Afghanistan and sent to Guantanamo Bay. He was tried and designated an enemy combatant by a special military commission set up by the Bush administration. Human rights advocates raised concerns that the commissions violated constitutional rights, as defendants had limited access to legal representation and were not allowed to see the evidence against them.

Hamdan petitioned for his release, claiming that his detention, the military commissions, and the conditions at Guantanamo Bay violated the Geneva Conventions’ protections for prisoners of war. Lower courts upheld the commissions, finding that the president had inherent constitutional authority to establish them.

In 2006, five justices of the Supreme Court held that the military commissions were unconstitutional because the president’s authority, at most, extended to convening military commissions that complied with U.S. military and international laws. The justices found that the administration’s military commissions were inconsistent with the U.S. military’s Code of Justice and the Geneva Conventions.

The Court’s decision seemed to be a win for detainees’ civil rights, but its effects were not long lasting. Congress passed a series of laws, including the Military Commissions Act, that expressly authorized the military commissions while making it nearly impossible for those held at Guantanamo to challenge their detentions.

Boumediene v. Bush

Bosnian police detained Lakhdar Boumediene and five other Algerian nationals in 2002 under suspicion of plotting an attack on the U.S. embassy in Bosnia. They were transferred to Guantanamo Bay and labeled as enemy combatants. Boumediene challenged his detention by filing a habeas corpus petition, but it was initially denied because he was not a U.S. citizen.

The Supreme Court’s Rasul ruling should have cleared the way for Boumediene’s petition to be reviewed, but the Military Commissions Acts of 2006 complicated things. The law barred enemy combatants from filing habeas claims in Article III courts. Boumediene contended that military commissions did not provide an adequate substitute for habeas, and therefore this law violated the Suspension Clause of the Constitution, which states that “the Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.”

The Supreme Court ruled 5–4 in favor of Boumediene. Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy stated that the right to habeas corpus is so fundamental to the Constitution that its protection in Article I, Section 9, even predates the Bill of Rights. He noted that the Military Commissions Acts also raised separation of powers concerns, writing, “To hold that the political branches may switch the Constitution on or off at will . . . would . . . lead[] to a regime in which Congress and the President, not this Court, say ‘what the law is.’” While acknowledging that courts need to defer to the executive and legislative branches in some matters of national security, Kennedy stressed that protecting core American principles, like freedom from unlawful detention, is equally crucial for maintaining a just and constitutional government.

Zivotofsky v. Kerry

Menachem Zivotofsky was born in 2002 to a Jewish-American couple in Jerusalem, and his parents requested that his U.S. passport state his birthplace as “Jerusalem, Israel.” The U.S. State Department, which had a long-standing policy of maintaining neutrality on whether Jerusalem was Israeli or Palestinian territory, denied the request and simply listed “Jerusalem” as Zivotofsky’s place of birth.

The Zivotofsky family argued that the department was violating the Foreign Relations Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2003, which permitted U.S. citizens born in Jerusalem to designate Israel as their birthplace on their passports. However, the State Department contended that the law was unconstitutional, asserting that only the executive branch has the power to officially recognize international boundaries. President George W. Bush backed the State Department’s decision to ignore the law, emphasizing the importance of maintaining neutrality in a politically sensitive region.

The Supreme Court was asked to settle the crucial question: Did Congress have the power to change the long-standing policy of the State Department on the status of Jerusalem? In 2015, the Court sided with the State Department in a 5–4 decision, holding that the president has the exclusive authority to recognize foreign states and their borders.

Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that it is not the role of the courts to dictate international affairs, but the courts do have the duty to explain which branch has constitutional power when Congress and the president endorse conflicting foreign policies. Although the Constitution doesn’t explicitly assign the power to recognize states to the president, its Reception Clause gives the president the authority to receive (or reject) foreign diplomats, and historically, the Court has deferred to the executive on state recognitions. The ruling reinforced that any official documents issued by the State Department, including passports, must reflect the president’s stance on state borders.

Despite the Zivotofsky family’s loss in court, just a few years later, then-President Trump recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, and Menachem Zivotofsky became the first U.S. citizen to receive a passport listing his birthplace as “Jerusalem, Israel.”

Trump v. Hawaii

Following the Supreme Court’s conservative shift in 2017, it issued a vigorous defense of executive power in a case centered on President Donald Trump’s controversial “travel bans.”

On the 2016 campaign trail, Trump promised that one of his first actions in office would be a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on.” As president, Trump took a major step toward making good on his pledge. Among his first executive orders was a temporary ban on all travelers, refugees, and asylum seekers from seven majority-Muslim countries: Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. When that order was blocked by the courts, he issued a second version, but it met with a similar fate.

To sidestep accusations that he was targeting Muslim countries, Trump issued a third proclamation restricting travel from eight countries. The list included two non-majority-Muslim nations — North Korea and Venezuela — alongside Chad, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen. The revised ban, which was framed as a response to national security concerns, was challenged before the Supreme Court.

The justices were asked to consider whether the president could legally restrict entry into the United States of travelers and asylum seekers from specific countries, most of which had majority-Muslim populations. Opponents claimed that such a move would violate U.S. immigration law and the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, which bars religious discrimination. They cited a mountain of evidence that the national security justification for the ban was pretextual and that the ban was in fact motivated by animus against Muslims.

In a 5–4 decision, an ideologically split Court ruled in favor of Trump and affirmed the executive branch’s broad discretion in matters of national security. The majority opinion rejected comparisons between Trump’s travel ban and Japanese internment during World War II, as both Muslim and non-Muslim nations were included in the ban, while several Muslim-majority nations were excluded. The Court also held that it must uphold the ban as long as it was “plausibly related” to the government’s “stated objective” to protect the country, even if evidence indicated that the government’s stated objective was a pretext.

In a passionate dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor criticized the majority for its narrow reading of Trump’s proclamation and for ignoring Trump’s stated reason for the travel bans as a candidate. “The United States of America is a Nation built upon the promise of religious liberty,” she wrote, and “the Court’s decision . . . fails to safeguard that fundamental principle.”

Trump v. United States

Travel bans were far from the only Trump-related controversy in which the Supreme Court was asked to intervene. In 2024, the Court sided with Trump in a landmark decision that dramatically reshaped the landscape of presidential power.

The ruling came against the tumultuous backdrop of Trump’s post-presidency legal battles. After losing the 2020 election, Trump falsely claimed that the election had been stolen from him, despite numerous court rejections and affirmations from his own officials about the election’s integrity. His baseless claims culminated in the January 6, 2021, insurrection, when his supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol in an attempt to disrupt the certification of election results and block the peaceful transfer of power.

Trump was indicted over these events in 2023, making him the first former U.S. president to face criminal charges. His defense hinged on a novel claim: he was immune from prosecution for actions he took while in office because they were part of his “official acts” as president. Lower courts rejected this argument, affirming that presidential immunity did not extend to criminal conduct.

However, in a shocking twist, the six members of the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority ruled in Trump’s favor. The opinion established that presidents enjoy broad immunity from criminal prosecution for their “official acts,” which it defined very broadly. For instance, the decision treated Trump’s efforts to coerce the attorney general into bringing prosecutions for nonexistent voter fraud as “official acts.” In areas where the president is acting within his “exclusive sphere” of constitutional authority — that is, where Congress has no authority to act — that immunity is absolute. In areas where the president and Congress share power, that immunity may be only “presumptive,” but the Court set an extremely high bar for overcoming the presumption.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent was a forceful rebuttal to the majority’s decision. She warned of the dangerous precedent set by the ruling, arguing that it effectively allows presidents to break the law with impunity. The justice painted a stark picture of the potential for abuse, stating that under the majority’s reasoning, a president could theoretically commit severe illegal acts, such as ordering the assassination of political rivals or orchestrating a coup, without facing legal consequences.

“Even if these nightmare scenarios never play out, and I pray they never do, the damage has been done,” she wrote. “The relationship between the President and the people he serves has shifted irrevocably. In every use of official power, the President is now a king above the law.” Her poignant conclusion, “With fear for our democracy, I dissent,” underscored the profound and unsettling implications of the ruling for the future of American governance.

The Court’s decision in Trump v. United States marked a significant expansion of presidential privilege, raising urgent questions about the balance between executive power and accountability.