Spurred by false claims of voter fraud in the 2020 election, Texas enacted a voting law in 2021 with many egregious provisions. These ranged from new limits on assistance for voters with disabilities or language-access needs to the criminalization of election administrators who encourage mail voting. We cannot yet know the full impact of Senate Bill 1, let alone how it may exacerbate the restrictive voting system Texas had in place before the law’s passage. But data from the March primary shows that just one of the bill’s many provisions caused massive disenfranchisement and major racial disparities.

Under that new rule, voters were required to write their driver’s license number or partial Social Security number on their mail ballot application and mail ballot envelope. Whichever number they listed needed to match the number on file in their state voter registration. The rule created a variety of new ways in which a voter’s application or ballot might be rejected through no fault of their own. For instance, if a voter had listed their driver’s license number when they registered to vote (which may have been over a decade ago) but put their Social Security number on the application or ballot, it would have been rejected.

As reporting from this spring made clear, absentee applications and mail ballots were rejected at extremely high levels. These reports — relying primarily on aggregate, high-level data or data from a small handful of counties — showed that some 12,000 applications and 25,000 ballots were rejected during the March primary and that there were “signs of a race gap.”

While the early reporting pointed to the magnitude of the problem, thanks to a public records request filed by the Brennan Center, we now know more about which particular voters’ applications and ballots were rejected. We obtained individual-level data listing whether each voter in the state requested a mail ballot, whether that request was rejected, and if so, why it was rejected, and whether every voter cast a mail ballot, whether it was rejected, and if so, why it was rejected.

Our analysis of the data yielded troubling results. We found that the overwhelming majority of ballot rejections were due to the new ID number requirements imposed by S.B. 1 and that Latino, Asian, and Black voters were significantly more likely to have their mail ballot applications rejected than white voters. We also found that even when voters successfully applied to vote by mail, voters of color were far more likely to have their mail ballots rejected. This combination of application and mail ballot rejections left nonwhite voters at least 30 percent more likely to have an application or mail ballot rejected than white voters.

New Hurdles to Voting by Mail

S.B. 1 requires voters to list their ID number on both the mail ballot application and the envelope containing the ballot itself, but to make matters worse, the form for the ID number on the ballot envelope was located under the envelope’s flap. Some voters might not have seen the requirement. Others, as the Texas secretary of state’s office told NPR, might have “thought it was just an optional section” — after all, these voters already provided this information to officials when they applied to vote by mail. While these problems may be partially addressed through clearer ballot design, design interventions can only go so far because due to privacy concerns, the ID number field must remain under the envelope flap so it is not visible when closed.

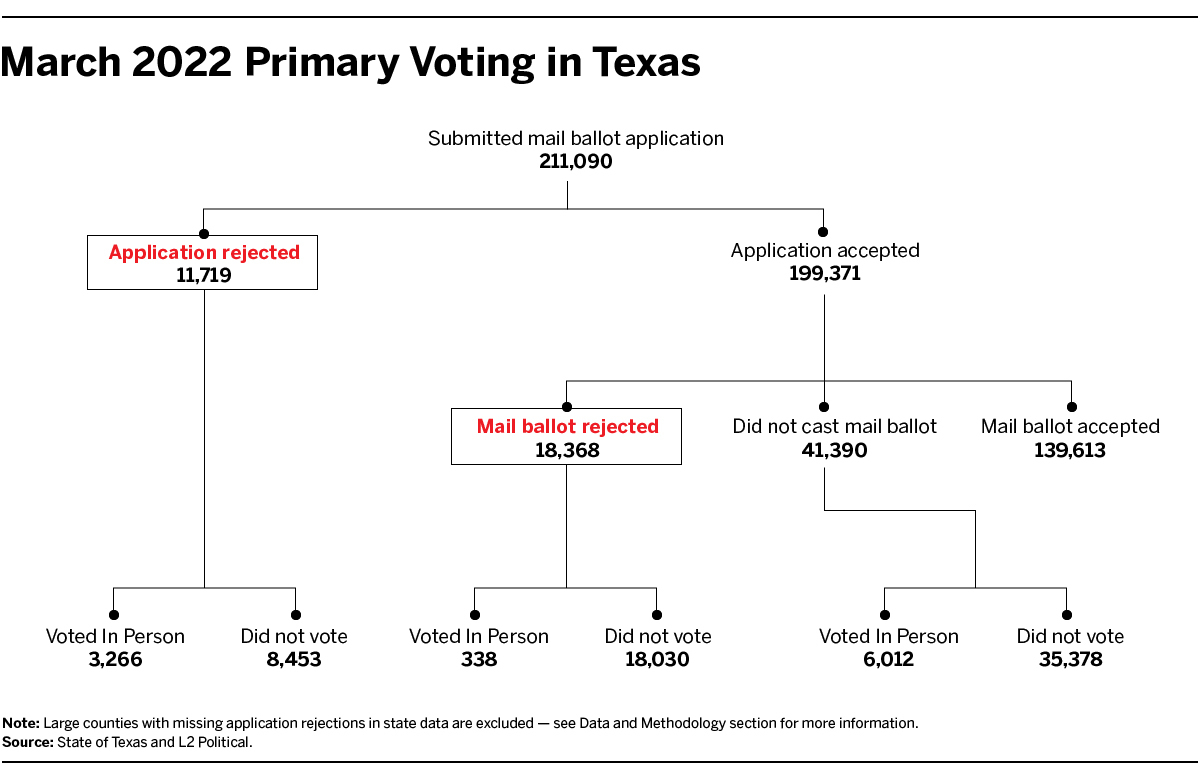

As the figure below makes clear, the new rules disenfranchised many voters. Nearly 12,000 people who requested mail ballots had their applications rejected. About one-third of those people ended up voting in person, and two-thirds did not vote at all. But even the voters who received a mail ballot weren’t out of the woods. More than 1 in 10 mail ballots cast by voters were rejected, and 98 percent of those voters ended up not voting in the primary at all. All told, only two out of every three voters who requested a mail ballot eventually successfully voted by mail.

In the figure below, we show that far more applications and ballots were rejected because of the new requirement to include this identifying number than for any other reason. In fact, more than 90 percent of rejected ballots were thrown out because of this problem. Stated differently, more than 6,000 mail ballot applications and 20,000 ballots were rejected as a result of this one change imposed by S.B. 1.

Racial Disparities in Mail Ballot Application Rejections

For the rest of our analyses, we look only at the share of applications and ballots rejected because of problems associated with new requirements under S.B. 1. Thus, if an application or ballot was rejected for another reason, it is included in the denominator but not the numerator in the following.

The applications of voters of color were rejected for S.B.1–related reasons at higher rates than those of white voters. In the figure below, we plot the application rejection rates for each racial and ethnic group. (For more information about data and methodology, see the section at the end of this piece.)

Although all racial and ethnic groups were more likely than white voters to have their ballot applications rejected, the rejection rate was highest for Asian voters, who were about 40 percent more likely to have an application rejected than white voters.

It is important to note that the application rejection data we received from the state is incomplete because some large counties did not report their information to the state (see the Data and Methodology section below for more information). These counties are excluded from the figure above. Because the excluded counties are considerably less white than the state overall, we likely understate racial and ethnic disparities in application rejection rates.

Racial Disparities in Mail Ballot Rejections

Successfully submitting an application for a mail ballot didn’t mean that voters would have no other issues voting. In fact, a much larger percentage of mail ballots than applications were rejected. Even more worryingly, the racial disparities in the ballot rejections were much larger than those in the application rejections.

As the figure below makes clear, white voters were the least likely to have their ballots rejected. All other racial and ethnic groups were at least 47 percent more likely than white voters to have their ballot rejected, even though they were also less likely to successfully request a mail ballot in the first place. Asian and Latino voters were each more than 50 percent more likely to have a ballot rejected due to a problem meeting S.B. 1’s new requirements than white voters.

While the figure below includes all counties (no counties were missing ballot rejection data, even if they were missing application rejection data), we show at the end of this piece that these results are consistent even when we remove counties that reported zero application rejections to the state.

Overall Rejections

It is important to note that these S.B.–1 related racial disparities compounded over the primary: nonwhite voters were less likely than white voters to obtain a mail ballot because their applications were rejected at much higher rates, and when they were able to obtain one, they were much more likely to have their ballot rejected.

In the figure below, we show what percentage of each group had either their application or their mail ballot rejected due to S.B. 1’s provisions. Voters who did not submit a mail ballot after successfully requesting one are excluded because their ballot could not be rejected. While 12 percent of white voters who requested a mail ballot had either their application or ballot rejected due to S.B. 1, these numbers were far higher for other racial and ethnic groups: more than 16 percent of each group saw either their application or ballot tossed. S.B. 1–related rejection rates were more than a third higher for Black and Latino voters than for white voters and more than 60 percent higher for Asian voters than for white voters.

• • •

Texas’s S.B. 1 is a prime example of the anti-voter legislation sweeping the nation. This analysis makes clear that just one of its many provisions is already causing serious problems in election administration, disenfranchising significant numbers of Americans — especially people of color.

Data and Methodology

Throughout our analyses, we rely on two primary data sources: the Texas registered voter file, which was provided by the data vendor L2 and dated May 7, and documents provided by the Texas secretary of state’s office in response to a public records request.

The registered voter file includes information on whether and how each voter participated in the March 2022 primary and in other recent primaries. L2 geocodes each voter to their home census tract. Using demographic data about voters’ census tracts and surnames, we use fully Bayesian Improved Surname Geocoding (fBISG) to estimate the probability that each voter is a member of different racial groups. We retain the posterior probabilities of the fBISG analysis. In each analysis, the denominator for each racial group is the summed probabilities that any individual voter is a member of that race. The same is true for the rejections.

In addition to the registered voter file, we leverage data provided by the State of Texas. These files include the voter ID number of every voter who requested an absentee ballot. If the application was rejected, it lists the reason for the rejection. Similar files are made available for voters who cast mail ballots, whether they were rejected or not. More than 98 percent of voters in the application and ballot data sets from the state are observed in the May voter file snapshot. We exclude those who are not matched. There is no reason to think this small number of nonmatches alters our conclusions in any way.

Unfortunately, the application rejection data is incomplete. The state data indicates that there were zero applications rejected in a number of large counties where we know that many applications were, in fact, rejected. All told, there were 12 counties with populations above 50,000 that reported zero rejected applications. We requested data from each of these counties, and we received responsive documents from three (Travis, El Paso, and Webb Counties), which prove that the state’s data set is incomplete. We know from deposition testimony of the Bexar County election administrator that the state data set is also missing rejections from that county. We therefore exclude Bexar County and the remaining eight counties (Bell, Ector, Fort Bend, Hays, Hidalgo, Nueces, Potter, and Waller Counties) in the above analyses on the assumption that it is not feasible that counties of this size rejected zero applications.

It is unlikely that the absence of data from these counties undermines our conclusions. Firstly, these counties are far less white than the counties included (27 percent versus 41 percent). Thus, unless these counties rejected far more applications from white than nonwhite voters, we are probably disproportionately missing rejected applications from voters of color, understating the racial disparities.

Secondly, even if we exclude only Bexar County — the only county for which we have definitive proof that data is missing — the disparities remain. The figures below make this clear. Thus, even if we assume that these disproportionately nonwhite counties did not reject a single application, significant statewide racial discrepancies remain.

Some smaller counties also reported zero application rejections. It is statistically more likely that a county with 10,000 residents would have zero rejections than a county with 100,000 or 1,000,000 residents.

However, if we exclude any county with zero application rejections, our results remain the same.