In the early 2010s, I traveled around the country observing dozens of redistricting hearings in the western United States and analyzing nearly a thousand comments provided by private citizens, public officials, and group representatives to redistricting authorities. The result was the first large-scale study of public involvement in the voting-map drawing process across multiple states, coauthored with UC Irvine Professor Bernard Grofman. We learned a lot about what makes comments effective — and how to avoid unhelpful comments.

The Census Bureau’s release of redistricting data on August 12 started a sprint to draw new election districts for the coming decade, a hugely important undertaking that can determine who is and isn’t represented in our government. Although everyday citizens sometimes voice doubt about whether their input at redistricting hearings matters, we were pleasantly surprised to see that about 44 percent of public comments that expressed a view on how a specific location should be handled by map drawers were adopted in the final congressional maps. But some comments were much more impactful than others.

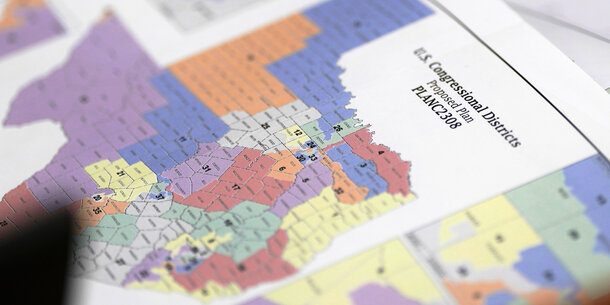

Who is in charge of the redistricting process varies: some states, largely in the West, use commissions to draw maps, while in others, legislatures are in control and pass a district map just like any other piece of legislation. But every state has a process for members of the public to comment on what they want to see in these new maps.

As the 2020 redistricting cycle gets going, our research into these public comment hearings leads to a few points to keep in mind as public officials and private citizens get ready to give their thoughts to the redistricting authorities in their states.

Give instructions to map drawers

In our study, we found about 36 percent of comments at hearings were infeasible and unable to be mapped. For redistricting authorities to be able to consider a given comment it must include two elements: a location and an instruction. For example, one of the most common kinds of comments is to suggest a city or neighborhood be kept together in a single district. Other examples of feasible instructions include a request to draw a group of cities together in a single district, use well-known boundaries like county lines or mountain ranges as borders between districts, or separate two cities into different districts.

By contrast, infeasible comments are ones that don’t provide a clear instruction to the map drawer. For example, a comment that a redrawn district include area to the southwest of the current district is difficult to implement in a final map without further guidance. A second, common refrain in states where the legislature draws the districts was for the legislature itself to give over the power of redistricting to a commission. While this comment may give the legislature some sense of what the people would like, it addresses the process — something that isn’t going to change immediately — rather than how to draw districts.

Think small

Our analyses of these comments revealed a strong relationship between the size of the area addressed in the comment and its likelihood of being adopted. Comments that touched upon a smaller area — on the order of a neighborhood in most cases — were substantially more likely to be adopted in final maps than comments that related to larger areas, like a suggestion to group a set of counties together in the same district.

At the smallest level of area in our set of comments, we found the adoption rate of comments was about 71 percent, and the adoption rate was about 41 percent at the middle of the distribution. Only about 15 percent of the comments dealing with the largest area were adopted.

Define your community and talk about its need for representation

For many, it is easiest to talk about the distinctive features of the places and people closest to one’s home. What defines your neighborhood? Is the area demarcated by reference to landmarks like parks, schools, roadways, or other geographic features? This sort of information is important for redistricting authorities to know about, especially because the salience of, say, a particular street is not always visually apparent to someone lacking local knowledge.

It is also helpful to talk about your community’s needs and how they can be addressed by representatives. For example, one common concern mentioned by residents in Long Beach, California, dealt with their desire to have the Port of Long Beach drawn into the same district as the city as a means to simplify efforts to mediate pollution originating from the port.

Or, communities may have diverging concerns about an issue. Karin MacDonald and Bruce Cain observed that residents on the south side of the Santa Monica Mountains in Los Angeles presented “compelling testimony” that susceptibility to fire hazards was justification for separating neighborhoods from the north side, where the risk of fires is lower.

Communities can also be defined by the people within them. For example, one person testifying before the California redistricting commission argued that the people living in “Lamorinda” deserved to be drawn into the same district due to their demographic profiles and high degree of interaction as observed through commuting patterns, little league sports, and the like. The only problem, as one commissioner pointed out, is that you cannot find Lamorinda on the map. Instead, this community is actually a combination of three separate cities in the state: Lafayette, Moraga, and Orinda. That the residents of the area even have a nickname for their community was remarkable for the commissioner at the time, and these cities ended up together in the newly drawn 11th District when the commission unveiled its congressional map for the state.

Online mapping programs can help persuade

Technology has made it easier than ever to produce maps showing the contours of your community in ways that can be translated into district plans. In our initial study, only about 3 percent of individuals testifying before a redistricting authority prepared a computer-drawn map. In the 2020 cycle, however, there are multiple platforms to easily make a map of your local community to share as part of testimony — including references to the same data that the redistricting authorities use when drawing maps — like Dave’s Redistricting App, Districtr, and Representable, each of which allows you to identify the area including your community. Testimony to a redistricting authority may carry more weight if that information is conveyed along with a visual reference to guide the hands of the line drawers.

Be prepared for less time

As the series of hearings proceeded, I noticed a few changes in how the meetings were conducted. First, limits on speaking time were introduced or, where they had been in place from the start, reduced in time to allow as many people as possible to speak. In one instance, the queue of people lined up to give feedback on draft maps was so long the hearing went beyond 1 a.m.

Therefore, it may be vital to be ready to quickly summarize the main points of your comments before your allotted time expires and not use a question from a commissioner or legislature to clarify your comments. If, however, your comments run long, you can also include longer comments and supplemental materials, like a map, in an email to the commission or legislature too.

Build neighborhood coalitions

These hearings also provide a great opportunity for coalition-building among your neighbors to collectively advocate for a particular district configuration. One effective example of this strategy was at a hearing in Brooklyn, when a spokesperson for a housing association presented a petition to the task force in New York that had split the membership of the housing association into two districts. The spokesperson described the community in question, observed that it was split, and then presented a petition signed by more than one thousand residents asking for the community to be kept in a single district. It worked, and the final maps had the housing association united.

However, there are dangers that the body receiving testimony from a group of neighbors will also become adept at recognizing repetitive testimony and weigh that content less than they might otherwise. Informal conversations I had with commissioners and legislators during my travels repeatedly made this observation. Spending the time to develop authentic testimony, spoken from the heart, is much better than having a number of people deliver identical, scripted testimony.

The public can and should play a role in the redistricting process. With some preparation and coordination among your neighbors, you too can be ready to step up to the podium and explain the contours of your communities to the authorities tasked with drawing new districts.