For voters of color, the fight for fair maps can seem endless. Another chapter starts Monday with a federal trial in a lawsuit that’s trying to undo a previous victory.

In January, Black voters in Louisiana won a hard-fought victory when the legislature redrew the state’s congressional map to add a second Black-majority district after a federal appeals court upheld a district court ruling that the prior map violated the Voting Rights Act.

But only days after the new map became law, unhappy white voters sought to block it in a different federal district court, contending that the new Black district was an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

Observers of Louisiana politics might feel like they are watching a poor remake of a movie that wasn’t very entertaining the first time around. After all, this isn’t the first time Louisiana has had two Black-majority congressional districts.

The last time Louisiana fought over its congressional maps was in the mid-1990s after the legislature (then controlled by Democrats) responded to the Voting Rights Act concerns from the Justice Department by linking communities in central and northern parts of the state to create a second Black-majority district, the first such district outside of New Orleans.

But, then as now, white voters attacked the new district. Relying on the Supreme Court’s opinion in Shaw v. Reno, which created the doctrine of racial gerrymandering, they were successful in getting courts to overturn two different versions of the district on the grounds that race predominated over “traditional districting principles” like the preservation of communities of interest, the minimization of political subdivision splits, and compactness when lawmakers made decisions about where to put district boundaries.

In the nearly three decades since, Black voters in Louisiana have only been able to elect their preferred candidates in one of the state’s six congressional districts, even while Black Louisianians have become nearly a third of the Pelican State’s population. In the other five congressional districts, artful linedrawing has divided the remaining Black population so that it is too small in any one district for Black voters to overcome some of the most persistently high rates of racially polarized voting in the country.

This decade, though, Black voters decided to renew a legal push for a second Black district, on the grounds that the state’s congressional map ran afoul of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

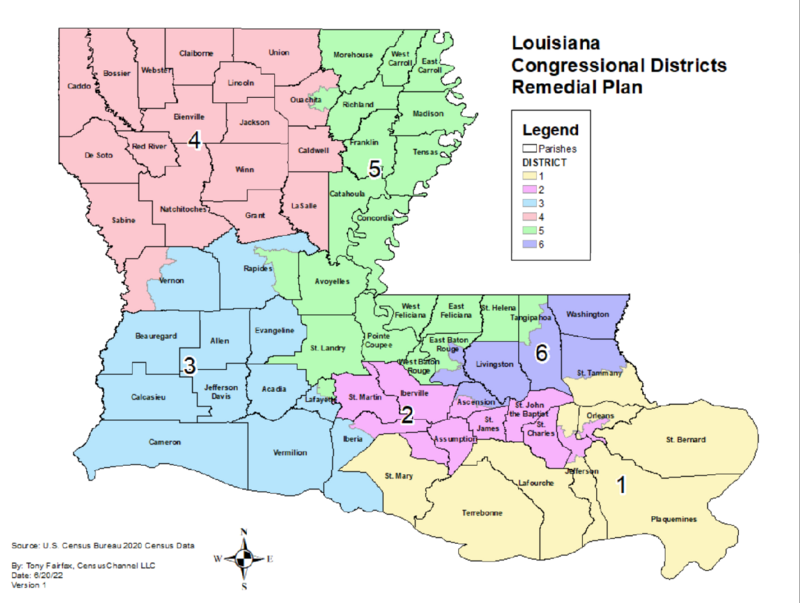

In their suit, they argued that significant Black population growth in East Baton Rouge Parish, now the state’s most populous and fastest growing parish, meant the area could anchor a compact second Black-majority district that joined heavily Black parts of Baton Rouge with parishes along the Mississippi River Delta on the eastern side of the state. In court filings, Black voters offered LA-05 in the map below as one possible configuration of such a district.

The district court agreed and ordered the legislature to redraw the map to create a second Black-majority congressional district. Republicans were successful in stalling implementation of a new map for the 2022 election, but after an appeals court upheld the ruling, Louisiana surprised many observers by suddenly giving up the fight — with a twist.

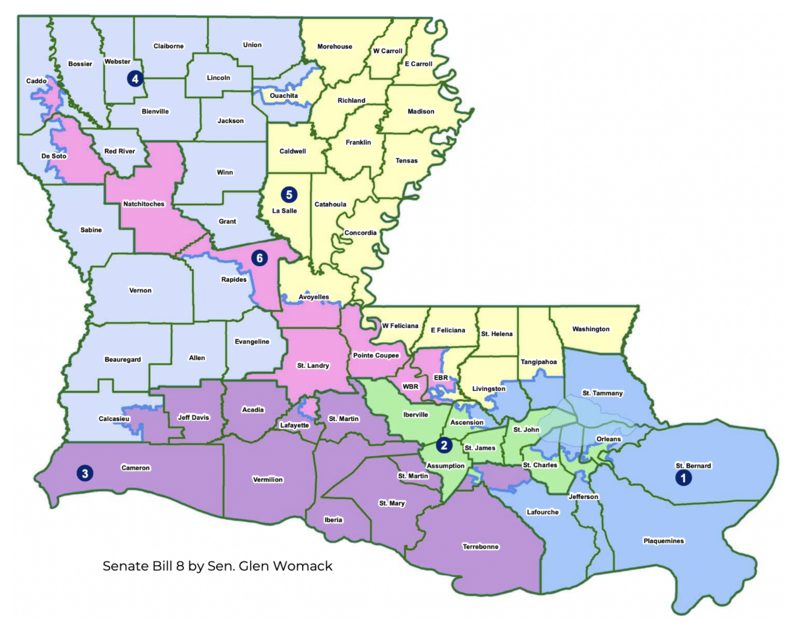

Rather than adopting a map with a Mississippi Delta-centered Black-majority district like the one proposed by Voting Rights Act plaintiffs, lawmakers radically transformed LA-06, the southern Louisiana-based district of Republican congressman Garrett Graves, into an elongated district running northward from Baton Rouge in the southeastern part of the state to Shreveport in the northwestern corner of the state, near its border with Texas.

In their court papers, white racial gerrymandering plaintiffs make much of the new, more sprawling district’s passing resemblance to one of the Black-majority districts invalidated by courts in the 1990s.

Louisiana officials and Black plaintiffs from the original Voting Rights Act case, however, strongly reject the contention that the new district is merely a racial gerrymander redux. They correctly point out that what matters under the “predominance” standard in racial gerrymandering law is not the shape of a district but the motivations behind its design. When courts struck down Louisiana districts in the 1990s, they did so because Louisiana legislature’s driving consideration in crafting the invalidated districts was race. Although lawmakers in the 1990s offered various non-racial rationales for the districts’ configurations, the court rejected them as “patently post-hoc rationalizations” unsupported by contemporaneous evidence.

This time, by contrast, officials and Voting Rights Act plaintiffs say bare-knuckle politics and community of interest considerations drove the design of the district, not race alone. To be sure, as in every Voting Rights Act case, race may have been a consideration, but it did not predominate.

As evidence, they point to legislative debates where lawmakers explained that their prime motivation in rejecting more compact versions of a Black-majority district in eastern Louisiana was to ensure that favored Republican incumbents had safe seats, especially Rep. Julia Letlow (LA-05), whose northeastern Louisiana district would have been dismantled under Black plaintiffs’ proposed map. By alternatively converting LA-06 into a new Baton Rouge to Shreveport Black-majority district, Republicans could both protect Letlow and ensure that House Speaker Mike Johnson (LA-04) and House Majority Leader Steve Scalise (LA-01) had “solidly Republican districts at home so that they can focus on . . . national leadership.” (According to a number of reports, several high-ranking Republicans were also only all too happy to use the map redraw to get rid of Graves, who has been at odds with both Gov. Jeff Landry (R) and Scalise in recent years — a reminder that the politics of map drawing sometimes can be intensely personal.)

They also spotlight legislative floor debates showing that another key motivation for the design of the redrawn LA-06 was to keep communities of interest centered around the Red River Valley and Interstate 49 corridor together given their “shared industry and commerce” and other socioeconomic interests. That the parishes along these corridors have substantial and in some cases majority Black populations does not make the process predominately driven on the basis of race.

With the 2024 election cycle underway, the new case is proceeding to trial at an unusually fast pace. Although the plaintiffs filed their case only at the end of January, the three-judge panel overseeing it scheduled a trial for April 8 to 10 and indicated that it expects to rule shortly thereafter given what the state has said are unmovable election-related deadlines.

If white racial gerrymander plaintiffs succeed in their challenge, Louisiana’s congressional map would have to be redrawn yet again, perhaps by a special master. An adverse ruling also could throw Louisiana’s 2024 election in disarray and potentially leave in place a map with only one Black-majority district if courts conclude there is not enough time for a new map.

Black voters in Louisiana have waited nearly 30 years for a fair map. If courts now snatch away their hard-won victory for yet another election cycle, it will be a stark reminder of how frayed legal protections for voters of color have become — and how important it is for Congress to renew and strengthen them.