In March 2022, the Ohio Redistricting Commission was running six months behind schedule to produce state legislative maps. The Ohio Supreme Court previously ruled that three sets of maps drawn by the politician-run commission were unconstitutional. The court’s latest order required the politicians in charge of redistricting to hire independent mapmakers to achieve what they could not: draft maps that reflect Ohio voters’ preferences.

But instead of following through with the independent experts’ proposals, a few legislators on the commission had other plans. Late in the evening on the day of the court’s deadline, they introduced a separate set of legislative maps, drawn by one party’s staffers in a back room outside of public view, that looked eerily similar to previously rejected maps. The commission’s majority approved the eleventh-hour plan — abandoning the professionals, disregarding the will of the citizens, and sending the court maps that would once again be ruled unconstitutional.

That scene during the state’s contentious and protracted redistricting process after the 2020 census stayed with one voter. Michael Ahern from Blacklick, a suburb of Columbus, said that the meeting “epitomized the hubris of politicians ignoring the process.”

This fall, Ahern is supporting Issue 1, a constitutional amendment on the November ballot that would replace the existing commission, comprised entirely of politicians, with an independent citizen-led process. The amendment, submitted by the nonpartisan group Citizens Not Politicians and endorsed by the Brennan Center, would establish a 15-member panel of citizens — five Republicans, five Democrats, and five independents representing diverse ideological, demographic, and geographic perspectives — to produce fair and equitable voting maps.

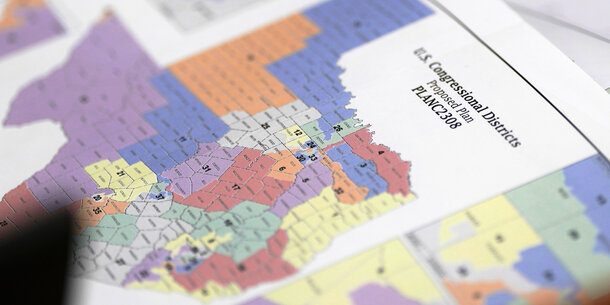

Under the current system, the boundaries for both congressional and state legislative districts are determined by partisans with a stake in the outcome. The commission, which draws the lines for the state legislature, is made up of seven members: four lawmakers appointed by state legislative leaders, as well as the governor, secretary of state, and state auditor.

For many voters in Ohio, the problem with the redistricting process lies with putting politicians rather than citizens in charge of drawing districts.

“If you’re a politician and you got a chance to draw a line so you keep your job, you’re going to do that,” said David Dilly, a Coshocton native who served in the Vietnam War and is a second-generation mine worker. “Take that out of the equation.”

In the 2022 redistricting cycle, the Ohio Supreme Court repeatedly struck down gerrymandered maps produced by the commission. The court found that the maps did not follow the constitutional requirement that the distribution of seats closely align with each party’s share of votes in recent statewide elections.

Ohio’s lasting legacy of manufacturing electoral outcomes through gerrymandered maps stretches back to before the Civil War. After Congress passed the Apportionment Act of 1842, the Ohio General Assembly convened a special session that year to redraw the state’s districts. Democrats controlled both legislative chambers over the Whig Party (it was more than a decade before the Republican Party was founded). As a result, they proposed a plan that packed Whig majorities into only a handful of the state’s 21 districts, leaving almost all the others safely in the hands of Democrats. The Whig members of the Ohio legislature resigned en masse, preventing the chambers from reaching a quorum to pass the plan. The move delayed the state’s congressional elections and sank the proposed plan.

In the succeeding years, Ohio politicians often used gerrymandering as a tool to pick which voters they represent rather than empowering voters to select their representatives. The result has been political representation far detached from the preferences of voters.

“The gerrymandering has become more egregious rather than less,” Ahern said. “Partly because the gerrymandered legislature then has become more emboldened and more hyper-partisan, and partly because there aren’t adequate court remedies.”

A broken politicians’ process

Dilly, the veteran who is also backing the amendment, described his visit to his state representative in Columbus last year ahead of an August special election called by the state legislature. The election was to vote on a legislatively referred constitutional amendment that, if passed, would implement onerous requirements for future citizen-led ballot initiatives, making them far more difficult, if not impossible, to pass.

As he implored his representative to vote against the amendment, Dilly said he was left with the impression that his representative was thinking, “I don’t care what you think. This is how I’m going to vote.” Voters rejected that measure.

Dilly isn’t the only one who feels that without competition and accountability, lawmakers in the state aren’t working for voters.

“The things that the majority of Ohioans agree on don’t actually happen,” said David McElfresh, a firefighter from Newark, which sits about 40 miles east of Columbus. “I just don’t feel like democracy is democracy.”

In 2022, the state supreme court rejected five proposals for state legislative maps and two for congressional maps, ruling them all unconstitutional. After the politicians on the commission refused to comply with the court’s orders to draw fair legislative maps, a federal court ordered the state to use the unconstitutional state legislative maps for the 2022 midterms. In 2023, the commission voted unanimously to approve new gerrymandered statehouse maps shortly after the Citizens Not Politicians Amendment was announced. Meanwhile, Ohio voters have been left with unfair maps, little transparency, and no remedy to address them.

The redistricting cycle displayed both the brazenness of the politically driven commission to deliver political advantages for one party and the degree to which that partisanship emboldens the existing body to ignore judicial review of maps.

The result was a “mockery” of the redistricting process, according to Nadia Zaiem, a lifelong resident of the Cleveland area who signed the petition to put the amendment on the 2024 ballot.

“We kept politicians in the process, and they were supposed to follow a set of guidelines to make sure that the maps in the districts that they drew were fair,” she said of the existing politician-dominated system, which includes constitutional bans on gerrymandering. “They have shown that they are not capable of doing this fairly and constitutionally. So it has to be taken away from them.”

A citizens-first solution

This November, Ohio voters will have the opportunity to overhaul the process and insulate it from politicians, lobbyists, and other political insiders. The 15-member panel would bar current politicians, political party officials, candidates, or anyone who served in or ran for office in the prior six years from serving on the commission. The ban would also extend to employees, contractors, or immediate family members of disqualified individuals.

The measure would also require the committee to follow certain rules for the map-drawing process to eliminate closed-door sessions and invite public input, such as holding at least five regional hearings across the state before maps are drawn, five more regional hearings once the initial maps are drafted, and any additional hearings to adopt the final maps. The final map would require approval by nine commissioners, including at least two Republicans, two Democrats, and two independents. (The inclusion of independents on the panel is important in a state where roughly 70 percent of registered voters are unaffiliated with a party.)

The result must also reflect the preferences of voters across the state, comply with the Voting Rights Act, preserve communities with shared representational needs, and provide equal opportunities for minority voters. The amendment establishes robust checks to ensure a fair and transparent process, such as safeguards against deadlock and allowing for the removal of rogue commissioners who engage in misconduct or do not adhere to rules.

The amendment secured its place on the November ballot in July when the secretary of state approved more than 530,000 signatures across 58 counties, far exceeding the required thresholds for citizen-initiated ballot measures. If the measure is successful, the new citizen redistricting panel will draw new maps for the 2026 elections.

Still, there is an uphill battle to November. Last month, the Ohio Ballot Board certified language summarizing the amendment that includes a wholly dishonest description of the measure that would likely mislead voters. But supporters of the amendment are not deterred. They are confident it will pass.

“I think that Ohio voters have shown the last couple elections that they’re smarter than the politicians think they are,” Zaiem said. “They’re not going to give up easily.”