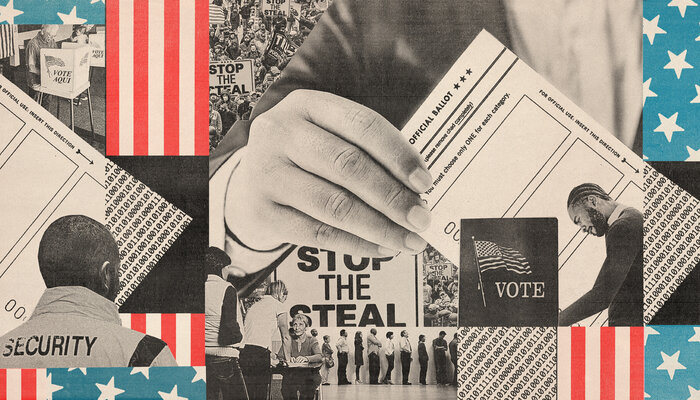

What are the gravest threats to the security and integrity of U.S. elections? Over the past decade, the answer to that question has evolved. In addition to foreign cyberattacks and influence campaigns, dangers such as intimidation of election workers and conspiracy theorists assuming election administration positions now put U.S. democracy at risk. In the lead-up to the next presidential election, the United States must adjust to this changed landscape and ensure that the democratic process is protected when the nation goes to the polls.

In 2016, Russian cyberattacks on election infrastructure highlighted the need to strengthen the resilience of U.S. election systems. As a result, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) designated election systems as critical infrastructure, 1 and federal, state, and local officials worked together to reinforce them against cyberattacks. New threats, largely stemming from amplified efforts to fuel distrust in U.S. elections via the spread of election falsehoods, must be met with the same urgency.

The deliberate spread of election falsehoods — including denial of the 2020 presidential election results — culminated in the attack on the U.S. Capitol in 2021 that President Donald Trump instigated in an attempt to overturn a free and fair election. It has also led to serious challenges to the integrity of future elections, including partisan interference in election processes, intimidation and violence against election workers, and the risk of insider attacks in which the very government workers tasked with administering U.S. elections directly endanger election security. Since the 2020 election, advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have made it possible to produce vast volumes of text peppered with falsehoods; generate convincing deceptive images, video, and audio; and distort public figures’ words and actions at a previously unseen scale. These threats are likely to grow ahead of 2024. Powerful politicians, including presidential candidates, and national pundits continue to encourage disruption of the election process and cast doubt on results.

Abroad, U.S. elections have become a battlefield in the conflict over the global order. Heightened stakes in Ukraine and other flash points have increased the motives for powerful countries to interfere in future contests. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence recently warned that the Russian government “views U.S. elections as opportunities for malign influence as part of its larger foreign policy strategy,” and the Kremlin continues to look for ways to undermine American democracy.2

Not only have foreign and domestic threats to American elections evolved and metastasized but they also fuel one another. In 2020, election falsehoods were mostly spread by domestic political actors, who used tactics similar to those that Russia exercised four years earlier, while Russian agents amplified these lies. 3 After the election, Iranian operatives drew on the anger some Americans felt about the outcome to incite violence against election officials. 4 Even if foreign cyberattacks are not technically successful, they can still exacerbate domestic distrust of elections. 5 In fact, foreign actors do not even need to attempt a cyberattack to cast doubt on election security, as Iranian operatives demonstrated in 2020 with a video that created the illusion that someone had hacked a state voter registration system.6

Taken together, these trends have rendered U.S. election systems increasingly vulnerable. Over the next 18 months, policymakers must address four overlapping threats to election security: the spread of false information to undermine election results and prevent citizens from voting; harassment, intimidation, and physical violence against election workers and officials; insider attacks; and cyberattacks against election infrastructure.

These challenges require a whole-of-government response. At the federal level, DHS — in particular, its Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), which defends and secures the nation’s critical infrastructure — along with the Election Assistance Commission (EAC), the FBI, and other federal agencies should direct more resources to combat these threats. Additionally, the Department of Justice (DOJ), via its task force on election threats, should bolster its relationships with and provide further guidance to local law enforcement and election officials.

State legislatures should make it easier for officials to combat election lies, protect election workers, prevent insider attacks, and guard against cyber threats. New laws should give election officials more flexibility to count ballots faster, expand protections for elections workers, and outline restrictions to safeguard election systems from tampering and unauthorized access.

Finally, state and local election officials should expand their efforts to protect elections, including preempting misinformation with official web pages that disprove rumors about election systems; adopting measures to prevent, detect, and respond to insider threats; and creating contingency and communications plans in the event of a cyberattack.

The time is now to defend the election process against future threats. American democracy depends on it.

Endnotes

-

1

DHS, “Statement by Secretary Jeh Johnson on the Designation of Election Infrastructure as a Critical Infrastructure Subsector,” January 6, 2017, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2017/01/06/statement-secretary-johnson-designation-election-infrastructure-critical. -

2

Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community, February 6, 2023, 15, https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2023-Unclassified-Report.pdf. -

3

Isabelle Niu, Kassie Bracken, and Alexandra Eaton, “Russia Created an Election Disinformation Playbook. Here’s How Americans Evolved It,” New York Times, October 25, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/25/video/russia-us-election-disinformation.html; and National Intelligence Council, Foreign Threats to the 2020 US Federal Elections, March 10, 2021, https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ICA-declass-16MAR21.pdf. -

4

Ellen Nakashima, Amy Gardner, and Aaron C. Davis, “FBI Links Iran to Online Hit List Targeting Top Officials Who’ve Refuted Trump’s Election Fraud Claims,” Washington Post, December 22, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/iran-election-fraud-violence/2020/12/22/4a28e9ba-44a8–11eb-a277–49a6d1f9dff1_story.html. -

5

Matt Vasilogambros, “Russian Cyberattack Could Capitalize on Election Doubts,” Pew Charitable Trusts, April 22, 2022, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2022/04/22/russian-cyberattack-could-capitalize-on-election-doubts. -

6

Sophia Tulip, “Iranian ‘Hacking’ Video Fabricated to Push Election Disinfo,” Associated Press, November 7, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/fact-check-2020-election-fake-hacking-video-034512361997.