Executive Summary

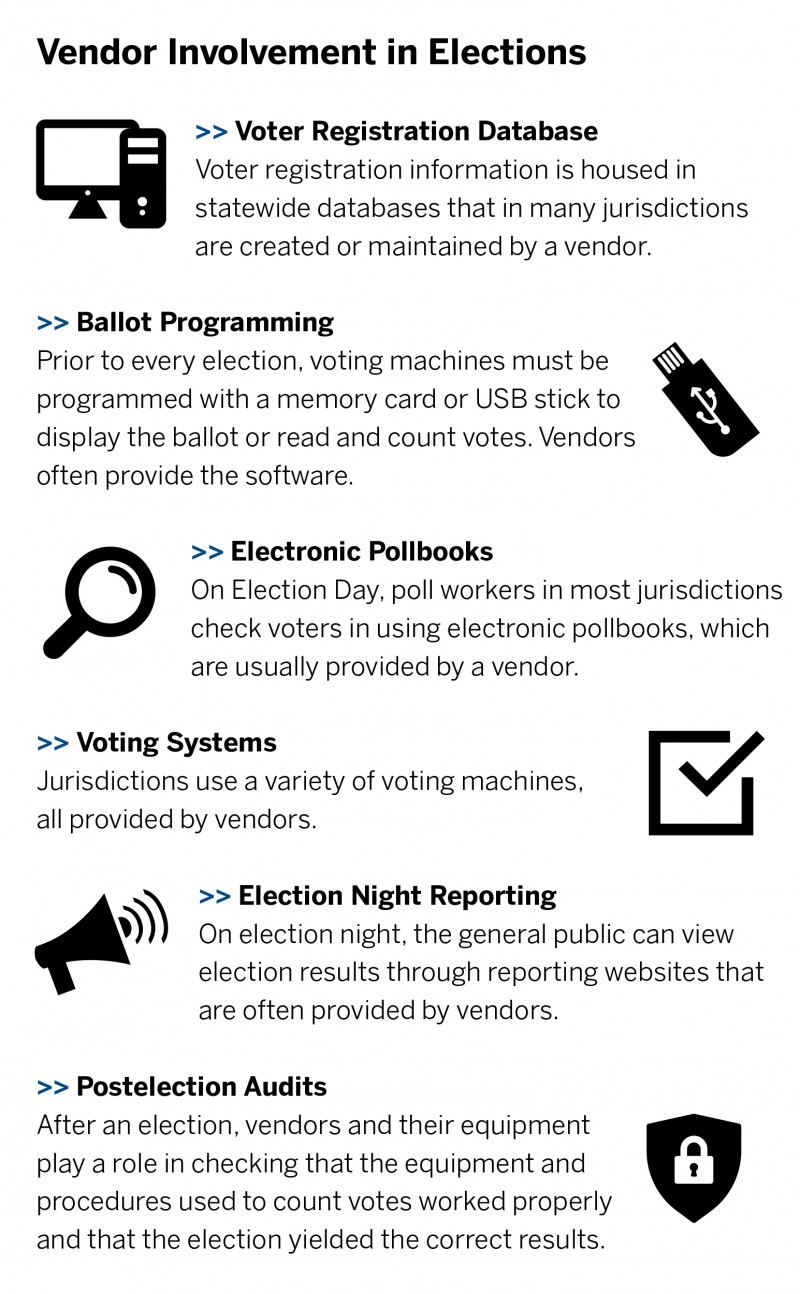

More than 80 percent of voting systems in use today are under the purview of three vendors. footnote1_wbwJKh9QLV5hcvymFcpbt0k0cJojzxAEGTxPYz94qM_d4q0ySHLLCyL1 Kim Zetter, “The Crisis of Election Security,” New York Times Magazine, Sept. 26, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/26/maga- zine/election-security-crisis-midterms.html. A successful cyberattack against any of these companies could have devastating consequences for elections in vast swaths of the country. Other systems that are essential for free and fair elections, such as voter registration databases and electronic pollbooks, are also supplied and serviced by private companies. Yet these vendors, unlike those in other sectors that the federal government has designated as critical infrastructure, receive little or no federal review. This leaves American elections vulnerable to attack. To address this, the Brennan Center for Justice proposes a new framework for oversight that includes the following:

- Independent oversight. A new federal certification program should be empowered to issue standards and enforce vendors’ compliance. The Election Assistance Commission (EAC) is the most logical agency to take on the role. Unfortunately, from its founding, the EAC has had a history of controversy and inaction in carrying out its core mission. In this paper, we assume that the EAC would be charged with overseeing the new program, and we make a number of recommendations for strengthening the agency so that it could take on these additional responsibilities. Whichever agency takes on this role must be structured to be independent of partisan political manipulation, fully staffed with leaders who recognize the importance of vendor oversight, and supported by enough competent professionals and experts to do the job.

- Issuance of vendor best practices. Congress should reconstitute the EAC’s Technical Guidelines Development Committee (TGDC) to include members with more cybersecurity expertise and empower it to issue best practices for election vendors. (The TGDC already recommends technical guidelines for voting systems.) At the very least, these best practices should encourage election vendors to attest that their conduct meets certain standards concerning cybersecurity, personnel, disclosure of ownership and foreign control, incident reporting, and supply chain integrity. Given the EAC’s past failures to act on the TGDC’s recommendations in a timely manner, we recommend providing a deadline for action. If the EAC does not meet that deadline, the guidelines should automatically go into effect.

- Vendor certification. To provide vendors a sufficient incentive to comply with best practices, Congress should expand the EAC’s existing voluntary certification and registration power to include election vendors and their various products. This expanded authority would complement, and not replace, the current voluntary federal certification of voting systems, on which ballots are cast and counted. Certification should be administered by the EAC’s existing Testing and Certification Division, which would require additional personnel.

- Ongoing review. In its expanded oversight role, the EAC should task its Testing and Certification Division with assessing vendors’ ongoing compliance with certification standards. The division should continually monitor vendors’ quality and configuration management practices, manufacturing and software development processes, and security postures through site visits, penetration testing, and cybersecurity audits performed by certified independent third parties. All certified vendors should be required to report any changes to the information provided during initial certification, as well as any cybersecurity incidents, to the EAC and all other relevant agencies.

- Enforcement of guidelines. There must be a clear protocol for addressing violations of federal guidelines by election vendors.

Congressional authorization is needed for some but not all elements of our proposal. The EAC does not currently have the statutory authority to certify most election vendors, including those that sell and service some of the most critical infrastructure, such as voter registration databases, electronic pollbooks, and election night reporting systems. For this reason, Congress must act in order for the EAC or other federal agency to adopt the full set of recommendations in this report. footnote2_YWexJe6Fiiwx-Rpjb8hfTdU0lBZgyTTmjLfOfgBQE4_dbUipUDwBBZf2 The For the People Act, H.R. 1, 116th Cong. (2019) and the Securing America’s Federal Elections Act, the SAFE Act, H.R. 2722, 116th Cong. (2019) both would accomplish much, but not all, of this report’s rec- ommendations. Specifically, these bills provide for EAC oversight of a broader array of election system products and vendors in exchange for receipt and use of federal funds but do not provide for ongoing certification and monitoring of vendors. They also do not speak to best practices on personnel decisions or supply chain security. These bills also do not fully address how to define foreign ownership and control. Where this report’s recommendations could be accomplished by adopting one of these bills, we have attempted to flag that for the reader. Regardless, the EAC could, without any additional legislation, issue voluntary guidance for election vendors and take many of the steps recommended in this paper as they relate to voting system vendors. Specifically, it is our legal judgment that the EAC may require, through its registration process, that voting system vendors provide key information relevant to cybersecurity best practices, personnel policies, and foreign control. Furthermore, the EAC may deny or suspend registration based on noncompliance with standards and criteria that it publishes.

Ultimately, the best course of action would be for Congress to create a uniform framework for election vendors that adopts each of the elements discussed in this paper. In the short run, however, we urge the EAC to take the steps it can now to more thoroughly assess voting system vendors.

End Notes

-

footnote1_wbwJKh9QLV5hcvymFcpbt0k0cJojzxAEGTxPYz94qM_d4q0ySHLLCyL

1

Kim Zetter, “The Crisis of Election Security,” New York Times Magazine, Sept. 26, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/26/maga- zine/election-security-crisis-midterms.html. -

footnote2_YWexJe6Fiiwx-Rpjb8hfTdU0lBZgyTTmjLfOfgBQE4_dbUipUDwBBZf

2

The For the People Act, H.R. 1, 116th Cong. (2019) and the Securing America’s Federal Elections Act, the SAFE Act, H.R. 2722, 116th Cong. (2019) both would accomplish much, but not all, of this report’s rec- ommendations. Specifically, these bills provide for EAC oversight of a broader array of election system products and vendors in exchange for receipt and use of federal funds but do not provide for ongoing certification and monitoring of vendors. They also do not speak to best practices on personnel decisions or supply chain security. These bills also do not fully address how to define foreign ownership and control. Where this report’s recommendations could be accomplished by adopting one of these bills, we have attempted to flag that for the reader.