- Algunos políticos y grupos antiinmigrantes insisten en una lectura no literal de invasión e incursión predatoria para que la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros pueda ser invocada en respuesta a la migración irregular y el narcotráfico transfronterizo.

- La Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros discrimina contra los inmigrantes basándose en su país de ciudadanía y, de manera más amplia, en su ascendencia.

- Estos defectos deberían llevar a un tribunal a revocar la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros si la ley es otra vez invocada, así sea durante tiempos de paz o guerra.

Suscríbete aquí al boletín informativo del Brennan Center en español

¿Qué es la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros?

La Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros de 1798 es una facultad en tiempos de guerra que permite al presidente detener y deportar a los oriundos y personas ciudadanas de una nación enemiga. La ley permite al presidente señalar a estos inmigrantes sin una audiencia y basándose solo en su país de nacimiento o ciudadanía. Aunque la ley fue implementada para prevenir el espionaje y sabotaje extranjero en tiempos de guerra, puede ser —y ha sido— utilizada en contra de inmigrantes que no han cometido ningún acto ilícito, no han demostrado señales de deslealtad y están residiendo legalmente en los Estados Unidos. Es una facultad excesivamente amplia que puede violar los derechos constitucionales en tiempos de guerra y está sujeta al abuso en épocas de paz.

¿Se ha utilizado anteriormente la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros?

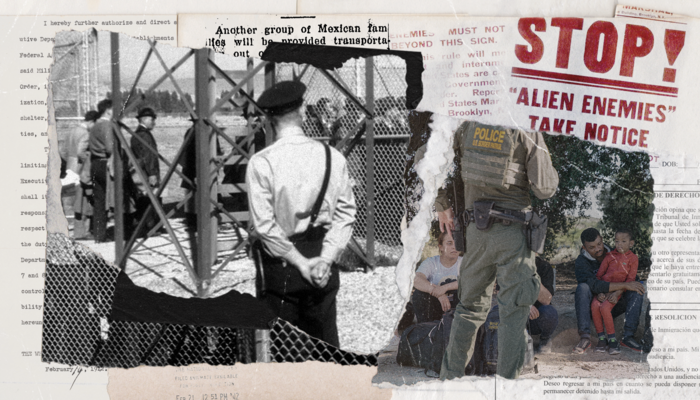

La Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros se ha invocado tres veces, cada vez durante un gran conflicto: la Guerra de 1812, la Primera Guerra Mundial y la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Durante la Primera y Segunda Guerra Mundial, la ley sirvió como una autoridad clave para las detenciones, expulsiones y restricciones de las que fueron víctima los inmigrantes alemanes, austrohúngaros, japoneses e italianos basándose solamente en su ascendencia. La ley es mejor conocida por su papel en el internamiento de los japoneses, una parte vergonzosa de la historia de EE. UU. por la cual el Congreso, presidentes y las cortes se han disculpado.

¿Bajo qué circunstancias puede un presidente invocar la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros?

El presidente puede invocar la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros durante una “guerra declarada” o cuando un gobierno extranjero amenaza con, o lleva a cabo, una “invasión” o “incursión predatoria” en contra del territorio estadounidense. La Constitución le da al Congreso, y no al presidente, la facultad de declarar la guerra, entonces el presidente debe esperar al debate democrático y a una votación en el Congreso para invocar la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros basada en una declaración de guerra. Pero el presidente no necesita esperar al Congreso para invocar la ley si se basa en una amenaza de invasión o incursión predatoria, o si está llevando a cabo una de estas. El presiente tiene la autoridad inherente para repeler este tipo de ataques repentinos —una facultad que necesariamente implica la discreción para decidir cuándo una invasión o incursión predatoria está en marcha.

¿Tienen que tomarse literalmente los conceptos invasión e incursión predatoria, o puede el presidente proclamar una invasión retorica?

Como han reconocido la Corte Suprema y los expresidentes, la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros es una facultad de tiempos de guerra promulgada e implementada bajo el poder de guerra. Cuando el Quinto Congreso aprobó la ley y la Administración Wilson la defendió en la corte durante la Primera Guerra Mundial, lo hizo bajo el entendimiento de que las personas no ciudadanas con conexiones con un beligerante extranjero podrían ser “tratadas como prisioneras de guerra” bajo las “leyes de guerra según la ley de las naciones”. En la Constitución y en otros estatutos de finales de 1700, el concepto invasión se utilizó literalmente, típicamente para referirse a ataques de gran escala. El concepto incursión predatoria también se utiliza literalmente en escrituras de esa época para referirse a ataques un poco más pequeños, como la Redada de 1781 en Richmond liderada por el desertor estadunidense Benedict Arnold.

Hoy en día, algunos políticos y grupos antiinmigrantes insisten en una lectura no literal de invasión e incursión predatoria para que la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros pueda ser invocada en respuesta a la migración irregular y el narcotráfico transfronterizo. Estos políticos y grupos ven a la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros como una facultad súper poderosa para la deportación. Pero la lectura que proponen de la ley está en conflicto con siglos de práctica legislativa, presidencial y judicial, y todas confirman que la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros es una facultad de tiempos de guerra. Invocarla en tiempos de paz para saltarse las leyes convencionales de inmigración sería un abuso tremendo.

¿Hay alguna manera en la que la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros puede ser utilizada fuera de la guerra?

Aunque la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros solo se ha invocado durante grandes conflictos, los presidentes Woodrow Wilson y Harry S. Truman continuaron utilizando la ley después del cese a las hostilidades de la Primera y Segunda Guerra Mundial.

La Primera Guerra Mundial terminó en 1918, pero la Administración Wilson utilizó la ley para internar a inmigrantes alemanes y austrohúngaros hasta 1920. Y la Segunda Guerra Mundial terminó en 1945, pero la Administración Truman utilizó la ley para internaciones y deportaciones hasta 1951.

En sus fundamentos del fallo Ludecke v. Watkins de 1948, una pequeña mayoría de la Corte Suprema ratificó la extensión fuera de la guerra de la que dependió la Administración Truman para aplicar la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros, argumentando que no era competencia de la rama judicial cuestionar al presidente sobre asuntos tan “políticos” como cuándo termina una guerra y expiran las facultades de tiempos de guerra.

¿Si las cortes ratifican el uso posguerra de la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros, podemos confiar en ellas para que anulen los abusos a la ley en tiempos de paz?

Las cortes deberían anular cualquier intento por utilizar la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros en tiempos de paz, pero la doctrina de las cuestiones políticas puede prevenir que lo hagan. Esta doctrina advierte a las cortes no atender temas que caen dentro de los deberes constitucionales del Congreso y del presidente y que carecen de estándares jurídicos para su resolución. Las cortes han utilizado la doctrina de cuestiones políticas para evitar resolver demandas que tocan temas sobre la guerra y paz, así como otros asuntos sensibles de política exterior.

En los años 90s, las cortes dependieron de la doctrina para desestimar demandas que decían que la Administración Clinton estaba permitiendo una “invasión” migratoria, en violación del Artículo Cuarto de la Constitución. En otros casos, las cortes han sostenido que si el presidente reconoce a un poder extranjero, para la rama judicial este reconocimiento es vinculante. Si las cortes fueran a emplear el mismo raciocinio aquí, permitirían al presidente invocar la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros basada en una “invasión” o “incursión predatoria” de migrantes por parte un cartel que se alega está actuando como un gobierno extranjero de facto.

¿Hay alguna manera de esquivar la doctrina de las cuestiones políticas?

Según el dictamen de Corte Suprema en Baker v. Carr de 1962, la cual formalizó la doctrina de cuestiones políticas, las cortes pueden adentrarse en ámbitos políticos para corregir “un error obvio” o “un ejercicio del poder manifiestamente no autorizado”. Las cortes nunca han dependido de esta protección, sin embargo, y hay muy poca claridad sobre cuándo y cómo se puede aplicar.

Pero, aunque las cortes se rehúsen a cuestionar si hay una invasión o incursión predatoria por parte de un gobierno extranjero, todavía pueden seguir considerando cuestiones constitucionales u otras demandas en materia puramente de derecho sobre la autoridad del presidente. Como el Brennan Center ha explicado en su informe sobre la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros, la ley despierta serias preocupaciones sobre las garantías constitucionales a la protección igualitaria y el debido proceso. Aunque no es el enfoque de nuestras investigaciones, la ley también despierta preocupaciones según las leyes de Estados Unidos que implementan el Protocolo sobre el Estatuto de los Refugiados de 1967 y la Convención contra la Tortura, además de las teorías constitucionales de la separación de poderes que limitan la autoridad que el Congreso puede delegar al presidente. Las cortes pueden anular o limitar la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros por cualquiera de estos motivos.

El Congreso, también, puede derogar la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros para prevenir o parar su abuso. La diputada Ilhan Omar, demócrata de Minnesota, y la senadora Mazie Hirono, demócrata de Hawái, ya han presentado propuestas en la Cámara y el Senado para derogarla —la Ley de Vecinos No Enemigos. El Congreso debería aprobar la propuesta sin demora antes de que un futuro presidente intente abusar de la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros.

¿Cuáles son las preocupaciones del Brennan Center sobre la constitucionalidad de la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros?

La Quinta Enmienda protege a los ciudadanos estadunidenses e inmigrantes en contra de la discriminación y violación de derechos perpetrados por el gobierno federal. Las cortes, por lo general, anulan las políticas que discriminan basándose en una clasificación sospechosa, como la raza o ascendencia, y las políticas que infringen los derechos fundamentales.

La Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros discrimina contra los inmigrantes basándose en su país de ciudadanía y, de manera más amplia, en su ascendencia. El alcance de la discriminación de la ley es evidente en sus fundamentos legales y en su historia. Según su texto, la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros abarca no solo a los ciudadanos de un país beligerante pero también a los “oriundos” —o individuos que nacieron en un país enemigo pero que han renunciado a su ciudadanía y ya no deben lealtad a ese país. La aplicación de la ley a “oriundos” aclara que la ley se enfoca en la herencia cultural por nacimiento, y confunde la ascendencia con la deslealtad en tiempos de guerra. En las décadas posteriores a la Segunda Guerra Mundial, cuando el Congreso y la rama ejecutiva se disculparon por el int¿Qernamiento de los japoneses, alemanes e italianos, reconocieron que los inmigrantes habían sido señalados, regulados e internados bajo la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros en base a su ascendencia.

La Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros también incumple con el derecho a ser libre de la detención civil indefinida, como reconoció la Corte Suprema en 2001 en el fallo Zadvydas v. Davis. Las detenciones en tiempos de guerra son necesariamente indefinidas, ya que los estados no negocian la duración de sus hostilidades al inicio de un conflicto. Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, algunos inmigrantes fueron internados por más de 10 años, a pesar de que eran civiles y que no se les acusara por ninguna actividad irregular.

Considerablemente, la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros es contraria a un tema central en el derecho estadunidense y su ethos: el derecho a ser juzgado como un individuo, particularmente para decisiones de alto impacto como la detención o deportación. A lo largo de la historia de EE. UU., solo otra ley autorizó las deportaciones basándose en la identidad —la Ley Geary de 1892. La ley se aprobó como parte de la exclusión china, y refleja otro vergonzoso capítulo en la historia de Estados Unidos que ha sido objeto de disculpas congresionales y presidenciales —al igual que la internación bajo la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros.

Estos defectos deberían llevar a un tribunal a revocar la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros si la ley es otra vez invocada, así sea durante tiempos de paz o guerra. Pero deberían también impulsar al Congreso a derogar esta anticuada y peligrosa ley para que la nación no repita los errores del pasado.

¿Si se deroga la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros, quedaría Estados Unidos vulnerable durante los tiempos de guerra?

Cuando el Congreso aprobó la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros de 1798, los Estados Unidos no tenía leyes de inmigración y apenas había un naciente derecho penal. El país no tenía agencias federales de inteligencia o de policía.

Hoy en día, secciones enteras de los códigos de inmigración, penal y de inteligencia están dedicados a prevenir y erradicar el espionaje, sabotaje y otras actividades malignas —sin importar la ciudadanía o pertenencia étnica del perpetrador. Cientos de miles de empleados federales trabajan en agencias dedicadas a proteger el territorio y la seguridad nacional. Estas agencias tienen mecanismos de vigilancia y otras herramientas especializadas para identificar a los individuos que puedan estar conspirando con una potencia extranjero en contra de los Estados Unidos.

En la era moderna, no es un argumento admisible decir que depender de medidas sobredimensionadas basadas en la identidad, como la internación o expulsión bajo la Ley de Enemigos Extranjeros, es necesario —incluso en tiempos de guerra.

Traducción de Laura Gómez