All politics is local, but local institutions often evade national scrutiny.1 City and county governments make policy decisions that impact daily life and animate political identity: how to run just and effective police forces, how to maintain roads and deploy emergency services, and how to operate public schools that educate and enrich future generations.2 They have also become cultural flash points in social movements for racial equity and LGBTQ+ rights. Local elections offer critical opportunities for communities to address the issues that most directly affect them, participate in the political process, and cultivate political talent for higher office.

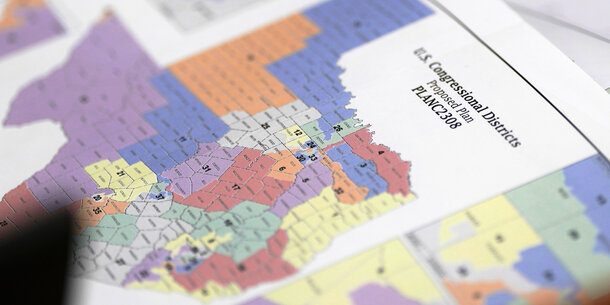

Since 2010, rapidly growing communities of color have reshaped Georgia’s demographic and political makeup, yet the state’s county governing structures have been slow to reflect that change. Many factors contribute to these disparities, among them the electoral practices shaped by the Republican-dominated state legislature that create structural barriers to elected office. Compounding this problem are the legislature’s unprecedented efforts to intervene in local redistricting precisely where communities of color are tipping political scales.

This report draws on 2023 state voter file data to analyze the racial and gender identity of current members of Georgia’s 159 county commissions and their respective school boards.3 People of color are dramatically underrepresented among Georgia’s county government officials. They constitute nearly 50 percent of the state’s population, yet as of February 2023, only 27 percent of county commission seats and 29 percent of county school board seats statewide were held by people of color. The average Georgia county has about half as many people of color on its county commission and school board as would be predicted given its population and school enrollment composition, respectively. Underrepresentation is more pronounced in these local offices than in state or federal ones.

Ten counties where people of color make up more than 40 percent of the population are governed by county commissions in which every member is white. Statewide, at least 54 counties have all-white commissions. Latino and Asian underrepresentation is particularly egregious. Although Latinos make up 11 percent of Georgia’s population, only 3 of 811 county commissioners we identified and 2 of 913 county school board members we identified are Latino (0.3 percent). Asians constitute 4 percent of the state population, yet just 2 county commissioners and 1 school board member are Asian (0.2 percent).

Gender disparities in local representation are also stark. Men outnumber women on county commissions in Georgia by a ratio of more than five to one. Women of color, who make up more than 25 percent of the state’s population, hold just 8 percent of county commission seats.

Electoral structures that impede minority representation persist across Georgia counties. The sole-commissioner system — used by several counties in Georgia but nowhere else in the country — vests policymaking power in a single individual elected at large. No person of color has ever been elected as sole commissioner. In addition, nearly one in four counties elects all its commissioners at large — that is, from the entire county rather than from single-member districts. At-large and sole-commissioner systems elect only half as many commissioners of color as would be predicted when compared with districted or mixed counties, normalizing for each county’s demographics. Despite the long-standing academic consensus that at-large elections disadvantage minority voting power, the state kept most at-large and sole-commissioner systems intact in the 2021–22 legislative session even as it passed more than 100 local acts to redistrict county governing bodies.

Where the state legislature did act, it interfered in local map-drawing decisions in a manner that undermined minority representation. It broke with established practices by circumventing committee requirements for consent from the local delegation. The legislature did so primarily with respect to suburban counties where rapidly growing communities of color had recently elected a majority of people of color to their commissions. The state legislature also drew Black county commissioners out of their districts at a higher rate than it did for white county commissioners. Such moves could make it harder for them to retain their positions. In one case, the legislature even sought to cut short the term of a Black county commissioner.

Legal protections are needed to address these representational harms. Federal preclearance, which operates primarily at the local level, could create a critical check on the actions of discriminatory state legislatures. But the state and local governments do not have to wait for Congress to act and could enact state-level reform or local resolutions that improve redistricting processes. Only with fair representation can local governments meet the needs of all their constituents.

Endnotes

-

1

Tip O’Neill and Gary Hymel, All Politics Is Local and Other Rules of the Game (New York, NY: New York Times Books, 1995). -

2

Justin de Benedictis-Kessner and Christopher Warshaw, “Politics in Forgotten Governments: The Partisan Composition of County Legislatures and County Fiscal Policies,” Journal of Politics 82, no. 2 (April 2020): 461n1, https://doi.org/10.1086/706458. -

3

The 21 school boards that are not co-extensive with counties exhibit characteristics similar to those of the school boards we studied. Among those school boards, we found that 71 percent of members identified as white, 29 percent identified as Black, and less than 1 percent identified as another race. The racial composition of the student body in these districts was slightly less white than in school districts that co-extend with counties (71 percent of students were nonwhite, as opposed to 64 percent of students in the school districts that we studied). The average city school board district among these 21 boards achieved only 41 percent of the representation we would expect under parity.